Ironing Board Sam's Human Touch

by Jeff Hannusch

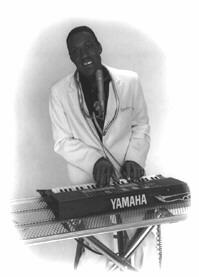

| IRONING BOARD BLUES Ironing Board Sam's Human Touch by Jeff Hannusch |

Though an active blues artist for nearly four decades, Ironing Board Sam's file is pretty slim.

Chalk up at least part of it to an inability to be in the right place at the right time and a mild distrust for record companies and producers. But, despite a brilliant mind for self-promotion and a gift for gadgets, the engaging singer and keyboardist has only recently released his first compact disc, The Human Touch.

But that's just part of the story. Master of many trades beyond his keyboard and vocal skills, Sam designs and sews his own intricate stage costumes. His inventions run from a baby bottle holder to his famous button keyboard. He says he can convert an automobile's gas engine to a diesel engine (and vice versa), and can produce free electricity for an entire apartment complex with a machine that has only five moving parts.

In the tiny apartment where he lives in New Orleans with his wife, packages of an air pollution control system, a recent invention made of mothball-sized filters for the nostrils, are arranged on boards ready for store display.

"I'd go further with these inventions, but they cost a lot of money to develop and kind of drag me down financially," says Sam. "Now if somebody were to give me, say, five million dollars and told me to work on them, that would be different. Besides, I've always felt I should be concentrating on music."

Ironing Board Sam was born Sammie Moore in 1939 in Rockhill, South Carolina. He spent a year and a half in college but had to drop out after he got married. Sam learned to play on his father's pump organ and joined several groups around the area as a teenager. His initial professional job was with Robert "Nature Boy" Montgomery, a blues singer and harmonica player who worked out of Miami.

Sam's confidence grew to the point where he formed his own group and worked small clubs around South Florida. In 1959, he moved to Memphis, where he picked up his colorful "nom de disque." Sam didn't have the regular legs to support his electric keyboard, so he improvised and used an ironing board stand, which he hid with a drape.

Club patrons began looking behind the drape and teasing Sam about the ironing board. He didn't like it at first, but he was tagged Ironing Board Sam, and the name stuck. One of the clubs where he regularly played even gave away a free ironing board on the nights he appeared.

In the mid-1960s Sam tried to audition for both the Stax and Hi labels, but was told they had more than enough artists to work with and to try somewhere else. It was Hi's Willie Mitchell who suggested Sam try Chess in Chicago.

"I did one session at Chess. When I went back to find if they were interested in recording me, I was told the producer I'd worked with had been fired," Sam says. "I was out in the cold. At that point I was totally discouraged with the record business. I knew I had what people wanted to hear, but the record companies wouldn't let me prove it."

Sam played around Chicago for about a year before Earl Hooker got him a lucrative gig at Jimmy Hunt's Lounge in Waterloo, Iowa. After a year and a half in Waterloo, Sam moved to Los Angeles for five years before returning to Memphis in 1973. Along the way be managed to cut 45 singles for Atlantic, Styletone, Holiday Inn and his own Board label, but nothing caught the public's attention.

A year later, Sam's journeys took him to New Orleans, where he got a regular gig at Mason's V.I.P. Lounge on South Claiborne Avenue, then the top black night spot in town. Sam, billed as "The Eighth Wonder of the World," teamed up with drummer Kerry Brown, and as anyone that saw the duo can attest, put on unforgettable shows.

Sam recently had invented the button keyboard. This instrument had two keyboards. The main one looked like a regular organ keyboard, but underneath it had been fitted with guitar strings. The keyboard was fed through a wah-wah and then into an amplifier, which would then produce the sound of guitar, organ, piano or a combination of the three.

The bass keyboard was made with 60 stationary upholstery tacks connected to electronic sensors. Sam ran a wire down his arm to his fingers, which conducted electricity to the buttons. The button board produced an electric bass sound, which filled out the sound of the duo considerably.

Blues was their staple, but their shows offered total entertainment. Sam would lift the keyboard off its ironing board, strap it around his shoulders and walk through the club as he played; Brown normally ended the night by dousing his drums with lighter fluid and playing while his kit went up in flames.

Sam says he spent a lot of time on that button keyboard. "It really had a different sound. I wanted to transistorize the button keyboard and took it to a guy to do while I went on the road," he explains. "When I came back, the guy said he threw it away. After that I went back to the regular electric keyboard -- I didn't have time to build another."

Sam cut another single in the late 1970s for Sansu, but he found the era generally rather frustrating. His gig at Mason's fell apart after the owner was busted for selling stolen New Orleans School Board food in his restaurant. And there was that other powerful adversary.

"Disco," says Sam. "After it came in it was hard to find work. I drove 1,500 miles in one direction looking for a place that had live music but couldn't find one. Then I drove 1,500 miles in another direction and couldn't find one.

"I even tried to learn to play disco, but I couldn't get the feel or the sound. I found out later you had to have a special keyboard to play it. That's when I decided to concentrate on trying to become more of an entertainer to draw attention to myself."

Sam's first step in that direction occurred in March 1978 when he made plans to play 500 feet over Jackson Square in a hot-air balloon. Sam was going to run cables down to a PA system and an amplifier on the ground while he played up in the clouds. After tacking posters all over New Orleans, the show had to be canceled because it was too windy and the balloon couldn't be stabilized to ensure his safety.

Sam's next piece of self-promotion involved a 1,500-gallon tank filled with water. He devised a way to play underwater and debuted the show at the 1979 New Orleans Jazz & Heritage Festival, which totally amazed an enthralled audience.

"I went on the road with the tank," said Sam. "But I found out the tank was too big to get into a lot of clubs. I worked some in Nashville and North Carolina before I moved back to Memphis. In Memphis I played in Handy Park and helped get Beale Street revitalized."

By 1982, Sam was back in New Orleans but still finding it hard to find work, necessitating yet another interesting form of self-promotion.

"People didn't want to hear live music," said Sam. "They just wanted to play records or the jukebox. I was hurting, so I decided to become the Human Jukebox. I built a giant jukebox that I fit inside with my keyboard and amplifier. I had slots built into it where people put money when they wanted me to play their request."

Sam busked in the streets in the French Quarter for several months when fate stepped in. The producers of the television program Real People saw Sam and shot a feature on him that aired nationally. In the interim the police arrested Sam on a noise violation, which took him off the streets and cost him $12. The attention from Real People got him some out-of-town dates and helped him get back into some New Orleans clubs.

By the late 1980s, Sam was playing Bourbon Street clubs with "Little George," a small, battery-operated toy monkey that played a snare drum. Sam devised a way to program Little George to play in synch with his drum machine, and he placed him on top of his keyboard so Little Sam actually appeared to be playing the drums along with Sam. The audiences in the clubs thought this was spectacular, so Sam, and Little George, rarely left without a stuffed tip jar.

By the early 1990s, Sam had made his first tour of Europe. He also cut an album's worth of material for then-Fats Domino manager Bob Vernon, a session that hasn't yet been issued.

He auditioned in 1991 for Orleans Records, arranged by Kerry Brown. The session was cut in less than 90 minutes, with Sam's vocals supported only by a vintage Wurlitzer piano. The audition tape has been issued as The Human Touch. Despite the sparse instrumentation and short recording time, Sam is extremely pleased with the results.

"Most of my other records I didn't like," says Sam. "The producers I worked with had never seen me play in clubs. They tried to change my style. When we cut The Human Touch, I was definitely in a groove. I played whatever I wanted, just like when I play in a club."

"I prefer doing my own material because I can feel it better. But recording is like playing a gig: You've got to play some things that are familiar in order to attract an audience. Then you can slip in your own songs and get people into who you are. That's always been my formula."

|

|