Luther Allison shows his blue streak

by Mark Edmonds

| SOUL FIXIN' MAN Luther Allison shows his blue streak by Mark Edmonds |

Maybe it's because absence makes the heart grow fonder. Or perhaps it's just years of hard work and mindfulness to his craft finally beginning to pay off. Whatever the cause, the gyre has undeniably turned in Luther Allison's favor and the "Soul Fixin' Man" is the new Big Thing in blues. After a decade of European "exile," the 56-year-old blues guitarist has hit home with a vengeance.

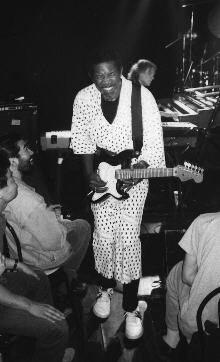

In 1995 he tore up most of the major U.S. blues festivals (Chicago, Mississippi Valley, the Poconos, San Francisco and King Biscuit among them) with sets of tight, no-b.s., rockin' blues. And his club dates -- averaging around three-and-a-half hours -- have provided galvanized audiences with an up-close look at a musician who remains friendly and respectful in spite of the awed attention he's drawn.

Blue Streak, his second Alligator Records release (1994's Soul Fixin' Man was the first), is the odds-on favorite to win a W.C. Handy award for Contemporary Blues Album of 1995, and he's a finalist in four other Handy categories.

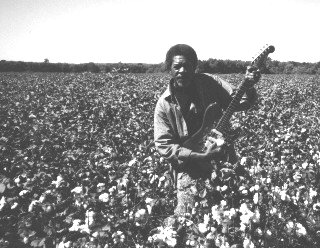

While he may be a recent discovery to blues newcomers on the strength of his tour schedule and radio airplay, Allison has a history as deep as his Southern roots. Born to a large clan that included ten brothers, a sister and two half-sisters, he was part of a family migration from an Arkansas cotton plantation to Chicago in 1951. He absorbed the sounds of Muddy Waters, Sonny Boy Williamson, Joe Hill Louis, Robert Nighthawk (a personal favorite), even the Grand Ole Opry, which radio brought into his boyhood home. He first began to experiment on guitar at age 10, eventually picking up techniques from his older brother, Ollie, who had a band that allowed young Luther to sit in periodically. Later, he was a high school classmate of Muddy's son and would stop in at the master's Chicago home to hear him rehearse.

Eventually Luther found the pull of show business stronger than high school. He dropped out to go full-time with his first band, the Four Jivers, in 1957. He began gigging all over the Windy City's West Side and suburbs and established himself throughout the area. After receiving encouragement from burgeoning star Freddy King, who was also playing the Chicago circuit at the time, he began to work his voice into his act.

Allison credits the big Texan's personal support with playing an important role in his development. King also helped Allison land his first series of steady gigs by endowing him with his prime week night engagement at Chicago's famed Walton's Corner club after his own records for the King label began selling. Allison, knowing an opportunity when he saw one, stepped right in -- and stayed five years.

The gig at the Corner ran into the mid-'60s. With a solid

reputation as one of Chicago's strongest players, Luther

decided to branch out.

He cut a session for One-Der-Ful in 1967 that was eventually purchased by Delmark Records.

He moved to Peoria and took several day jobs, commuting to Chicago for weekend

gigs. He made his first trip to California, stayed there for the

better part of a year, working clubs and cutting sides as a sessionman

behind fellow Chicagoans Shakey Jake and Sunnyland Slim.

He cut a session for One-Der-Ful in 1967 that was eventually purchased by Delmark Records.

He moved to Peoria and took several day jobs, commuting to Chicago for weekend

gigs. He made his first trip to California, stayed there for the

better part of a year, working clubs and cutting sides as a sessionman

behind fellow Chicagoans Shakey Jake and Sunnyland Slim.

He came back to play around Cook County as often as his schedule would allow. He worked on projects for Bob Koester's Delmark label as session player and with his own band, which he'd dubbed the Blue Nebulae in the psychedelic spirit of the time. One of the best recordings of Allison's career, Love Me Mama, was waxed during this period.

The early '70s marked the start of tough times for the blues. Gigs were harder to get, and they were much less lucrative. After falling out with Koester, Luther signed on with a most unlikely source: Motown. He made three albums for the Detroit label, of which only one, Night Life, even began to capture his essence. The company never adequately promoted the LPs and Allison's disappointment began to build.

He did, however, begin to acquire a solid following on the European festival circuit in the late '70s. In 1984, frustrated and tired of struggling in the States, Allison packed his bags and moved permanently to Europe, eventually settling in St. Cloud, France, near Paris.

He was following the same trail that a score of under-appreciated American blues and jazz musicians -- from Jack Dupree to Memphis Slim -- had blazed years before. Until a brief tour in 1994, Allison made only occasional return trips to the U.S. to play, visit family in the Windy City and indulge in fly fishing in the Minnesota lakes region.

His latest discs are accurate enough studio representations of Allison's sound -- one that fuses the Chicago West Sider's self-styled heavy and excited guitar playing to a contemporary blues musical base -- but they're not adequate preparation for what's in store when he steps onstage. This was the case at September's San Francisco Blues Fest and at Boston's House of Blues in November, where the singer/guitarist burned through sets.

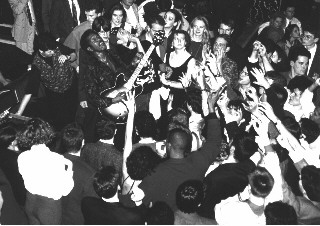

The mostly college-age kids at House of Blues were looking to break up the monotony of cramming for midterm exams with a few beers and a little music from the tall grey-bearded guy who innocently enough stepped on stage and plugged in his guitar. They got a bit more than that when Allison and Co. let fly with a series of overdriven grungy power-chorded vamps that stopped idle conversation in the back of the room and vibrated fillings in the mouths of those closer to the front. It was the aural equivalent of standing at ground zero when the Big One goes off.

Throttling down to a quiet shuffle, Luther surveyed the damage and broke into an ear-to-ear grin. Smiling, he stepped to the mic and yelled, "Hello, out there, everybody," as a stage assistant helped him change guitars. A chorus of whoops, hollers and raised fists rose up to greet him. "Do you want to hear the blues?" -- as if it were necessary to get the crowd's approval. "Yeahhhh," came the boisterous reply as Allison adjusted his guitar strap and plugged in again.

"Well, then," he said with a look of faux surprise as he laid his hands on the guitar strings. "Everybody get ready, y'all, 'cause we're gonna play some blues then." Bright notes cut through the smoky air like August lightning as the room went crazy.

Just another night on tour with the Soul Fixin' Man.

He might project an intimidating image as he snarls his way through his work onstage, but Luther Allison is a somewhat retiring, affable guy who doesn't mind chatting about a variety of topics when he's not working. Speaking recently in a series of formal and informal talks in San Francisco, Chicago and Boston, Allison was clearly pleased that his fortunes have turned upwards again in the U.S.

How does it feel to be back in front of U.S. crowds after more than 10 years? It seems like all of a sudden everyone's talking about Luther Allison.Well, (laughing) obviously I feel good about the idea. But let's face it, I still have to look at my self and look at the things I've done down the stretch. I mean, look how many musicians have come through and played beside me, and I'm workin' and they're not. It's sad that everybody can't be a success, you know? It's too bad, 'cause there are so many who are just as talented as I am.

To what do you attribute your success then, while others struggle?

Well, I think it's because I'm able to cross my thing over. And I can do the rock clubs if I have to. They'll say, "You have a little bit more than the blues, and the kids like you in the clubs." But I also try to help other folks out. Sometimes they (club bookers) will ask me, "Who else could we get?" And I start naming off people -- you know, like Lonnie Brooks. He and I, we came up real close together in the early days.

When you moved to France in 1984, did you see a change in audiences, and did they embrace you immediately?

Well, I first started going to Europe in the late '70s. I went in '76, '78, '79, and I met people there who believed and knew a lot more about Luther Allison than the people in the States. And not only on the promoters' level, but on the fan level.

That must have been a mind blower.

It kind of was. I mean, I was just looking for respect and recognition. I'd done the exact same thing here. And it hadn't really worked. But there it did. But you know, I still had a dream of being able to go back home and tour.

So what do you think it was about your music that people here didn't get at the time?

I don't know. At the time, I put myself in the same category as Jimi Hendrix -- and actually, early on up the ladder I was compared to him. I thought that was wrong, because I didn't know him, and I had no idea of what he was doing. I'm about 10 years older than he was, and I'd heard of his name down that stretch, and I started wonderin' (smiling), "Where did he see me at?" and "Where did he come from?" After I heard him, I thought that some of the things he did was me, and some of the things I did was him.

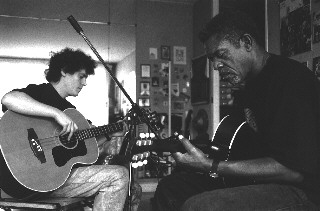

But my big thing was always the blues. I loved B.B. and Hubert and Freddy and Muddy. My thing was to try to be in that same ballpark with all those people. But do something different too. My thought was, "Suppose they all got together one day with me?" And what if I'd spent all of my time tryin' to learn how to play and sound like one of them? I would be lost. So my thing was to go inside of those people's trips, and do me -- just to have something different.

So I cut out all the drinkin' and hangin' out and stuff like that early on. I focused on how these people became how they were. They listened just like I did to other people and themselves, and they all came out different. I hope I do too. I want people to recognize Luther Allison when I play.

There's a feeling out there that you're delivering the goods -- playing hard, straight music -- which is, sadly, something that people have criticized Buddy Guy for not doing often enough lately. I know you guys are friends, but have you heard any of this?

Oh yeah, you hear about it all the time. You know, it's like he and I used to do these things all the time on the West Side -- they call it battle of the blues. It might be Buddy Guy, Magic Sam, Luther Allison one week; Buddy Guy, Freddy King and someone else the next week. It was like that Muhammad Ali/Joe Frasier thing for a lot of years. Who was going to beat who. Each one of us had our own fans, you know, to support us.

But let's talk about Buddy for a minute. Buddy Guy finally got a break and made it. And Buddy Guy deserves it. You understand what I'm sayin'? But now it's up to Buddy Guy to hold his championship. I'm not gonna go out there and try to put him down, and I'm not gonna go out there and say anything bad about him -- although maybe I don't agree with everything he does. But the fact is, you just gotta play, and if I know my friend, Buddy, he's also gonna do what I've tried to do over the years, which is to open the doors for our future musicians, or some of the others out there who need to take that other step. B.B. King's maybe been our savior for a long time, but I'm not sure that he's gone as far as Buddy Guy has to do that.

Speaking of time in the business, I'm willing to bet that you never thought 30 years ago that you'd hang in there to get to the point you're at now?

(Thinking) No way man.

So, within that context, what do you predict the future holds for Luther Allison?

(Shaking his head and smiling) Going ahead man. And I see it happening that way. I look in music magazines now and see things on Luther Allison, and my name's getting out there more, thanks to all the good people at Alligator Records and at my management company. And people like you. So it's coming along slowly. And I'm ready. I'm like a good plant that's been sitting there. I've been waiting for that bright sunshine to show up and shine in my back door someday. And now, heaven Lord, the clouds are partin'. Amen!

This is an abridged version of the Luther Allison interview.

For the complete article,

get the hard-copy version of BLUES ACCESS.

[Ed. note: Some of the information in this article was derived from a 1984 interview conducted during an international symposium at the University of Liège, Belgium, which appeared in The Voice of the Delta: Charley Patton and the Mississippi Blues Traditions, edited by Robert Sacre, 1987, Press Universitaires Liège.]

|

|