| ||

|

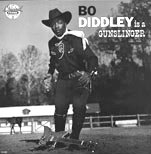

In the corral in a crisp, black Western outfit, a white scarf flowing from his neck, a revolver strapped to each leg, Bo Diddley could have been any one of the desperadoes on the westerns that dominated night-time television in 1960.

Except for one thing -- that cherry-red Gretsch guitar in the dirt at his feet. And the title of the album, nearly as provocative as the photo itself: Bo Diddley Is a Gunslinger. My teen-age musical tastes ran closer to the Kingston Trio than guitarslingers in those days, but the Western image worked its way inside my head and stayed put: Bo Diddley as Paladin.

Images like that are spread throughout a new book, The Blues Album Cover Art (Chronicle Books), in which editors Graham Marsh and Barrie Lewis trace recorded blues through its sleeve art. Many of the covers are reproduced at full size, an important element in considering their impact. It's a well-worn complaint that much enjoyment was lost in the transition from the 12-inch long-playing vinyl album to the five-inch compact disc, but as the book graphically illustrates, that doesn't make it any more invalid. Who would even notice the guitar, for instance, on a CD version of Gunslinger?

In a short essay that opens the book, writer Keith Briggs dates the "first serious album of black blues music" to Sam Charters' 1959 The Country Blues collection. Before then, as Briggs notes, recorded blues generally was categorized as a jazz subdivision or as a folk-music category, and several examples of each are included. Philips' issue of Robert Johnson's recordings in 1962, for instance, uses both, juxtaposing an old picture of rural Southern shacks against the title: Classic Jazz Masters: Robert Johnson, 1936-1937.

I was in no position to realize it at the time, but the Gunslinger

cover was aimed at white teen-agers like me as black artists like

Chuck Berry, Diddley and others crossed over to the pop charts.

It's a concept that major labels would continue to use,

with later '60s covers rendered by hip cartoonist R. Crumb

or the popular, wavy Erik Weber art of Chuck Berry's Live

at the Fillmore.

Chuck Berry, Diddley and others crossed over to the pop charts.

It's a concept that major labels would continue to use,

with later '60s covers rendered by hip cartoonist R. Crumb

or the popular, wavy Erik Weber art of Chuck Berry's Live

at the Fillmore.

John Lee Hooker's covers get the largest play, and for good reason. There are as many examples of evocative Hooker covers as there are labels releasing his work. The most conspicuous covers portray him as the consummate urban bluesman. On The Folk Blues of John Lee Hooker (Riverside, 1959), he is every inch the urbane bluesman: Bathed in a blue filter, he relaxes in front of a recording studio microphone (perhaps listening to a playback), gracefully cradling the strings of his Goya, a cigarette dangling elegantly between his fingers.

For That's My Story the next year, those same huge hands cradle his guitar as he stares down the cameraman. The same blue hue is used to enhance a below-the-belt shot of Hooker's electric guitar sitting on his leg for Chess' 1961 Plays and Sings the Blues. Another 1963 London release offers a full-sized, artsy, black-and-white Lawrence Shustak photo of the musician in serious contemplation, the veins standing out on his forehead. 1969's Black Rhythm'n'Blues is a close-up of Hooker resplendent onstage in a yellow shirt, black tie and matching leather jacket. Finally, on a 1971 Probe album Hooker is pictured with his band sitting on a city bus, which conjures another Paladin image: "Have Guitar -- Will Travel."

House of the Blues (Chess, 1960) foregoes Hooker's image for a color picture of three black women idling on the porch of a dilapidated Southern shack. A 1970 Wand LP, On the Waterfront, is fronted with a faded, 19th-century shot of cotton bales being loaded from a mule-drawn wagon onto a steamboat. Riverside used nothing more than a photograph of a bonfire for Hooker's 1958 Burning Hell; Vee Jay followed suit in 1962 by using a very similar one for its Burnin'.

Sometimes the covers fuel already existing stereotypes. A Frank Frost sleeve for Sam Phillips International overlays two crude pictures, the bluesman in bib overalls and a straw hat on one side, and standing awkwardly in a suit in front of a red-and-white background. Adobe Photoshop it isn't. Arthur Crudup is pictured in cheap coveralls looking down the railroad tracks, a guitar strung behind his back, on Mean Ol' Frisco, a 1960 album on Fire Records. Even a 1972 album for RCA has Crudup pictured like some kind of odd throwback with his antique guitar and amplifier.

Some of the covers are simply great photos cast in a particularly

dramatic way. Muddy Waters at Newport (Pye Jazz, 1960)

offers a color shot of a determined Waters, a primitive electric

pick-up attached to his F-hole acoustic guitar, preparing mentally

for the incendiary set he's about to play.

You can observe

the large fingers that gave Son House that distinctive snapping,

percussive sound and his charismatic, self-assured smile in the

Dick Waterman photo on Columbia's 1966 Father of Folk

Blues. Bukka White is pictured two years later in a quasi-NASA

outfit, the outsized rubber gloves cradling his ancient acoustic

for Memphis Hot Shots.

You can observe

the large fingers that gave Son House that distinctive snapping,

percussive sound and his charismatic, self-assured smile in the

Dick Waterman photo on Columbia's 1966 Father of Folk

Blues. Bukka White is pictured two years later in a quasi-NASA

outfit, the outsized rubber gloves cradling his ancient acoustic

for Memphis Hot Shots.

Necessity often forced great cover art. When Columbia issued King of the Delta Blues Singers in 1962, the company found no Johnson pictures. So Burt Goldblatt was commissioned to paint a man on a stool playing a guitar as seen from above, an image that has resonated with pre-compact disc era Johnson admirers. (One is left to imagine what the carnival self-portrait of Johnson in full size would have done, image-wise, if it had been the cover art.) For Vol. 2, Columbia relied upon brightly colored, stylized Tom Wilson paintings of Johnson's San Antonio recording session -- the artist on the front recording while facing the hotel-room wall and the producers in an adjacent room watching the dials on the back -- to great effect.

Perhaps the most evocative cover is the simplest: a 1960 Excello Lightnin' Slim album titled Rooster Blues. The fading reddish-orange cover has a simple silhouette of a rooster crowing atop a crude drawing of acoustic guitar. The authors got it from the collection of former Manfred Mann singer Paul Jones (see The New York Times September 22), and at least part of its charm is that you can see the outline of the very album that the teen-aged Jones plucked from an English record rack 35 years ago. Gazing at it, you can almost hear the scratches and pops.

There are lots of little epiphanies like that throughout The Blues Album Cover Art. Marsh and Lewis let the covers speak for themselves, allowing readers to come to their own conclusions. It's a colorful and important addition to blues culture and history.

-- Leland Rucker

|

|