A Rocky Road for the Roots Label

Story by Michael Dixon · Photos by David Stevens

| Fat Possum A Rocky Road for the Roots Label Story by Michael Dixon · Photos by David Stevens |

Fat Possum has had its ups and downs trying

to make a market for contemporary Mississippi blues.

Fat Possum has had its ups and downs trying

to make a market for contemporary Mississippi blues.

The rural blues of the Mississippi hill country is guitar music, often played using a glass or metal slide. It owes its rhythmic intensity to a fife-and-drum band tradition that has been popular in the area since the last century. The music is frequently simple and repetitive, but at its most compelling is profoundly powerful and hypnotic in its starkness. Born of crushing poverty and back-breaking labor, it was played out in a juke-joint atmosphere where solace often was sought from the daily strains of no opportunity and too many mouths to feed. Too, it might be heard being made at the end of a long day on the front porches of sharecropper shacks.

The prototypic hill-country artist was Mississippi Fred McDowell. He has long passed on, but R.L. Burnside, a neighbor of McDowell's when Burnside was a teenager, took up the torch. Although Burnside had recorded a number of albums (notably Blow My Blues Away on Arhoolie) and even played in Europe, he had not been able to support himself and his large family with his music.

But that was before Fat Possum Music was started in 1991 in Oxford, Mississippi, by Matthew Johnson and Peter Lee. Lee has since left, but Johnson has continued the label through some very lean and difficult times. Johnson, 28, grew up in Mississippi and loved its music. About six years ago he was having trouble maintaining his interest in pursuing a degree at Ole Miss. While trying to decide what to do about college, he began writing for Living Blues and struck up a friendship with then-editor Lee.

Johnson was bothered that although blues albums came from all over the United States and even Europe, there was a little-tapped pool of Mississippi talent. "There were a lot of local guys that were being overlooked completely," says Johnson. "We were in the middle of a blues revival, and there were all these people in Mississippi who had never made a first record."

Johnson and Lee began discussing the possibility of starting a record label to record and disseminate some of the local music. Initially, it seemed more a hobby than a business. "At first I think I said, 'Pete, we'll just do it Saturday mornings,' " Johnson relates.

But he had to overcome a distinct lack of business experience to make things happen. Even now, Johnson admits he has no real business sense. "I still don't really know how to balance a checkbook. I never had enough cash to do it right so it never really mattered, you know what I mean? I just figured if I could 'stay out on the road' long enough, something would happen."

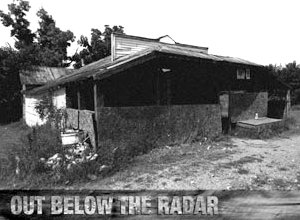

Johnson's use of a "road" metaphor is apt, since his talent search typically involved traveling the Mississippi countryside following leads on suitable musicians. Sometimes the leads involved trips to bars located in larger towns like Greenville or Clarksdale, but often were to out-of-the-way back country jukes that were pretty obscure, or "below radar," as Johnson puts it.

It was just such a setting, Junior Kimbrough's juke in Holly Springs (pictured above), where Johnson first made contact with Kimbrough and Burnside, the label's two major artists, a couple of years before the idea of starting a label had even occurred to him. It may have also been there that he met noted ethnomusicologist and writer Robert Palmer. The former New York Times writer's interest and involvement in Fat Possum has been invaluable. "Everything I learned, I have learned from Palmer, just from being around him," an appreciative Johnson claims. "He's one of the brightest people I ever met."

Palmer's contributions included helping select artists to record and producing the albums. Johnson would make cassettes of artists he had found who seemed promising. With Palmer's input, decisions were made about whom to record. Once that decision was made, Palmer often would come up from his New Orleans home and produce the session. He also wrote detailed and insightful liner notes.

Four hundred dollars diverted from a student loan financed the first Fat Possum release, Bad Luck City, by Burnside and the Sound Machine. The album was done without the help of Palmer. Bad Luck City, now out of print, perhaps failed to capture the true spirit of the local music, Johnson admits. "I don't know if what we had in mind is what we got. But I guess that's how a lot of first times go."

Undeterred, Johnson pressed ahead. He got an

infusion of some new money, this time from John Hermann of the

group Widespread Panic.

With Palmer as producer, the company next

released All Night Long by Junior Kimbrough.

After that came albums by Cedell Davis (Feel Like Doin' Something Wrong),

John "So Blue" Weston (So Doggone Blue) and Dave

Malone (I Got the Dog in Me), as well as Palmer-produced

second outings by Burnside (Too Bad Jim) and Kimbrough

(Sad Days and Lonely Nights).

With Palmer as producer, the company next

released All Night Long by Junior Kimbrough.

After that came albums by Cedell Davis (Feel Like Doin' Something Wrong),

John "So Blue" Weston (So Doggone Blue) and Dave

Malone (I Got the Dog in Me), as well as Palmer-produced

second outings by Burnside (Too Bad Jim) and Kimbrough

(Sad Days and Lonely Nights).

Favorable reviews in the music press, such as a four-star rating of Kimbrough's All Night Long in Rolling Stone and a New York Times feature gave the label exposure and a higher profile. But despite the excellent artist roster and a catalog of solid, satisfying and sometimes exceptional releases, finances were tough.

This came with the territory. Mississippi is a very poor state and, like many who live there, the musicians who make up Fat Possum's roster have had to struggle to stay above the poverty line. Some even lack a driver's license, let alone a vehicle in which to tour. "I don't know if I have any acts now who have valid driver's licenses," Johnson says. "I have assembled the biggest non-touring roster of any label in world history."

No matter how well-respected his catalog, actual distribution of the records was always a problem, and not an uncommon one for independent blues labels. Blues albums generally do not sell enough for someone to want to distribute them and do it well. "It becomes a logistics problem, having all these titles that sell basically a damn joke," explains Johnson. "No one wants a bunch of little products that noodle around for a couple thousand (units)."

A respite came in late 1994 from Capricorn Records. In the 1970s, Capricorn had been instrumental in the popularization of Southern rock by groups like the Allman Brothers and the Marshall Tucker Band. Out of business for years following its decline in the late '70s, the company was revived in the early '90s by its founder and owner, Phil Walden Sr., with Widespread Panic as one of the new Capricorn's first acts.

John Hermann, the group's keyboard player and Fat Possum silent partner, had included Junior Kimbrough material on one of Panic's albums and had Kimbrough open some of the band's shows. Kimbrough's efforts caught the attention of Philip Walden Jr., then director of business affairs and now general manager of Capricorn.

The younger Walden began traveling to Oxford, and he and Johnson became friends. "Some of the best times I had were going down there and hanging out in the office talking to Matthew about the way small record companies can run: two or three people putting out great records on a very limited budget and the kind of music that really matters," says Walden. "It was a great opportunity for me to be able to participate in some great music that Matthew had. There are not many record companies left like Fat Possum in terms of the amount of talent he managed to find."

Together, Walden and Johnson worked out a deal

that gave Capricorn the exclusive right to distribute Fat Possum

product. In practice, this meant that Capricorn would rerelease

previously issued Fat Possum titles with new covers, and put out

future Fat Possum releases. In return, Fat Possum received a royalty

for each CD sold and help with recording and overhead costs.

For Johnson and Fat Possum, the deal was a sweet one. "The contract was better than I'll ever be able to get again," he says. In early 1995, things started moving. The Fat Possum catalog came out under the Capricorn banner, several new recordings were made and two new discs released: Dave Thompson's Little Dave & Big Love and Paul "Wine" Jones' Mule. A major tour, the Fat Possum Mississippi Juke Joint Caravan, was undertaken.

But the agreement quickly started to unravel...

Webmaster's Note: The account of the ensuing legal actions could not be edited without potential unfairness to both parties, so that account will be left for the hard copy edition of the magazine. To get it, subscribe to BLUES ACCESS.

The legal wrangling was expensive for both parties, but especially draining to Johnson. For a year, he says, Fat Possum was "pretty much reduced to a name on a litigation paper. We moved out of our office, lost our studio room, quit recording. It's been a hard, awful year."

Albums scheduled for release, including new recordings by Burnside and Kimbrough, as well as an album reuniting Frank Frost, Big Jack Johnson and Sam Carr as the Jelly Roll Kings, never appeared. "It's one of the things with a lawsuit, this whole mess. It's always the artists who suffer the most," says Johnson, a comment which Walden seconded.

As part of the settlement, Capricorn will continue to distribute the current Fat Possum catalog, including the unreleased albums by Burnside, Kimbrough and the Jelly Roll Kings. Capricorn's foray into blues-oriented music continues on other fronts as well. Recent releases include former Wet Willie frontman Jimmy Hall's Rendezvous With the Blues and Johnny Jenkins' Blessed Blues.

Even through the hard times, Fat Possum and Johnson have been active independent of Capricorn. The recent film A Time to Kill features a gospel tune by the Jones Sisters, "Precious Lord, Take My Hand," recorded by Fat Possum. R.L. Burnside's new collaboration with the Jon Spencer Explosion on the Matador label, A Ass Pocket of Whiskey, was produced by Johnson. And Johnson expects to be signing new artists to his label shortly.

"I just want to go on," he says. "I don't want to sit in a room and hate somebody forever. What good does that do? I can see how in a lot of lawsuits that's what happens. Some of these can drag on for decades, and that's the last damned thing I want to do."