From Newport to Woodstock

by Tom Ellis III

| Paul Butterfield From Newport to Woodstock by Tom Ellis III |

The Woodstock Years

- Kierkegaard

Fear and Trembling

In the summer of 1963 a young record producer named Paul Rothchild had an idea. Rothchild had been working on projects since 1961, making a name for himself on recordings with many of the artists who made up a thriving folk-music scene in Cambridge, at that time at the center of this new style of pop music -- and gatherings known as hootenannies -- that was rapidly taking over on college campuses across the country. Best known for local Joan Baez, this scene was populated with a host of scholarly musicians, many of whom had hundreds of records and had made it their business to become familiar with and perform all kinds of folk music -- blues, jugband music, sea songs, spirituals, string band favorites and others.

Many of these musicians had become central figures at the folk festivals that had started to gain popularity in Philadelphia, Newport and in Canada at Mariposa. They had been drawn to Cambridge (and nearby Boston) by the notoriety of Baez, Burl Ives, Pete Seeger and the Kingston Trio, but most came because of a thriving club scene that offered performers and audiences multiple choices every night at venues like Club 47, the Unicorn Pub or at Cafe Yana, all featuring an ever-changing line-up of performers, each with a different musical interest and talent.

But of all the different types of folk music that could be heard on any given night, one seemed to have made the greatest inroads -- country blues. Performers like Mississippi John Hurt, Skip James, Lightnin' Hopkins, the Rev. Robert Wilkins and Sonny Terry and Brownie McGhee had been "rediscovered" by the folk scene, and at one point many white musicians took on the task of finding others -- some of whom had been recorded in the deep South by Alan Lomax for the Library of Congress years before -- as a cause. Their efforts brought some out of obscurity and into the public eye for the first time ever, leading to concert performances and recordings from these legends.

Although there were other folk scenes going on in the country -- at Albert Grossman's Gate of Horn in Chicago, in Greenwich Village, Ann Arbor and Berkeley and another centered around Ry Cooder in Southern California -- none had drawn the interest of recording companies like that of Cambridge. In fact, Maynard Solomon, president of Vanguard Records, and Jac Holzman, owner of Elektra Records, were primary members of a group known as the "Folk Mafia," that also included Seeger and Theodore Bikel, among others, and were regulars on the Cambridge scene. Rothchild, who had worked with most of the upcoming folk labels, was taken with the idea of a "blues project" that would feature the upcoming young white blues performers, most of whom lived in Cambridge. He took the idea to Elektra.

Holzman was convinced but worried that it would be too expensive. But Rothchild managed to bring it in for under $1,000, paying the artists $50 per cut. The result, The Blues Project, featured performers like Eric Von Schmidt, Geoff Muldaur, Dave Van Ronk, Danny Kalb and John Koerner and Dave Ray, with others like John Sebastian and Tom Rush in supporting roles. The album was an immediate success -- bolstering Elektra's confidence in Rothchild. And, as Rothchild would reminisce in Baby Let Me Follow You Down (the superb history of the Cambridge movement written by Jim Rooney and Von Schmidt, first published by the University of Massachusetts Press in 1979), it "allowed something else to happen about a year later, which was their first move into electric music. That was the Butterfield Band, which was a violent departure for that label."

![]()

Although still in their infancy, folk festivals were solidly established and respected by the early 1960s. Probably none was more highly regarded than the summer festival in Newport, founded by Grossman and jazz impresario George Wein, father of Newport's famous jazz festival. Although many of these annual events were renowned for their mix of folk talent, Newport was becoming as famous for its blues showcases; the 1964 Newport event may have been the greatest assemblage of original acoustic country blues artists ever. And by that time, Cambridge may have been the place for white blues musicians, who were always in attendance when their older idols came to Newport every July.

At the end of 1964, on New Year's Eve, Paul Rothchild had taken an excited phone call from Fritz Richmond, a member of the popular Kweskin Jug Band, himself a founder of the Cambridge scene. "We're in Chicago," he said, "and we just heard Paul Butterfield's new band, and it's the greatest thing you've ever heard. Get on a plane right now and get to Chicago." Rothchild took Richmond seriously -- his first record had been with him in 1961 -- and held his musical opinions in high esteem. "So I left the party and flew to Chicago and caught the last set. I walked into Big John's and heard the most amazing thing I'd ever heard in my life. It was the same rush I'd had the first time I heard bluegrass. I said to myself, 'Here is the beginning of another era. This is another turning point in American music's direction.' "

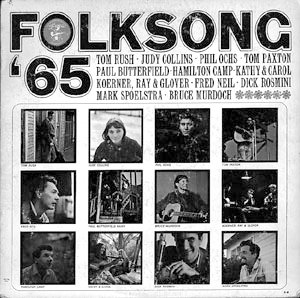

Rothchild was quick to sign the band to Elektra,

after a second guitarist named Mike Bloomfield was convinced to

join the group. A first recording effort was made but scrapped

(most of this was released in 1995 as The Lost Elektra Sessions),

but one song was salvaged and put on a $1.98 Elektra sampler titled

Folksong '65 that featured new Elektra artists (including

Rush, Judy Collins and Koerner, Ray & Glover). Samplers were

frequently released by Elektra, usually selling 20,000 to 30,000

copies. But not this one. "This sampler sold 200,000 copies,"

Rothchild says. "In a three-month period. Jac said, 'What's

going on?' And I kept saying to him, 'This tune is

going on: "Born in Chicago." Jac, we have a hit band

on our hands.' "

Folksong '65 that featured new Elektra artists (including

Rush, Judy Collins and Koerner, Ray & Glover). Samplers were

frequently released by Elektra, usually selling 20,000 to 30,000

copies. But not this one. "This sampler sold 200,000 copies,"

Rothchild says. "In a three-month period. Jac said, 'What's

going on?' And I kept saying to him, 'This tune is

going on: "Born in Chicago." Jac, we have a hit band

on our hands.' "

For a while Rothchild attempted to manage the group, booking them more and more outside of Chicago. By mid-1965 he was back in the studio again in New York working on what became their first Elektra album, and he was aware that the band was getting too big for him to handle. "During that time I called George Wein and asked him to put them on Newport," Rothchild says. "I called Albert Grossman and told him I had a band that was way beyond my capabilities and asked if he would consider managing them. He came down and heard them and said, 'I'll see them at Newport.' " Grossman was managing Dylan, Odetta, the Kweskin Jug Band and Peter, Paul & Mary, among others, and was, de facto, the most powerful manager on the folk scene.

That summer Geoff and Maria Muldaur were young newlyweds, and with Richmond and Bill Keith, members of the Kweskin band, an eclectic group that played an assemblage of blues, jazz, ragtime and jug music. They were deeply involved in the Cambridge scene, Geoff highly respected as both a musician and a blues scholar. Growing up in a musical household, he had been exposed to jazz, as well as Bessie Smith and other singers, while still in grade school.

"Then all of a sudden I heard Leadbelly, and I started scrounging through old 78s, discovering country blues records," says Muldaur. "It became one major portion of my love of music, although the jazz thing continued, as did other things. My first gigs in New Orleans were playing rural blues, which was a very odd thing for people to hear. And there were a couple of people in Cambridge doing that too, like Eric Von Schmidt and Dave Van Ronk. And each person who came on the scene there brought so much to it, because there were so few white guys playing the blues. When I arrived in 1960 there were things I brought that no one had heard. Cambridge was a very academic and open-minded scene, with people really digging into music."

The Butterfield Blues Band had been scheduled to perform twice at Newport -- a set the first night, as the gates opened (heard by few as a result) -- and then later the next day at a blues "workshop." "When we showed up at Newport, Bloomfield, who I already knew, was hooked up with this Butterfield guy. We'd already heard some Chicago blues, but we were very skeptical these guys could do it."

Music historians point to Dylan's decision to play an "amplified" set that year (which was actually only four songs) as the most memorable moment at Newport. "But to me the big breakthrough wasn't Dylan," Muldaur remembers. "In fact, I thought what he tried didn't work very well. But what did work well was the workshop with the Butterfield Blues Band. That was astounding.

"Newport was a real festival in that they had workshops all day all around the grounds; usually the workshops would draw a hundred people or so at most," Muldaur remembers. "So that afternoon they had one on urban blues, and Alan Lomax came out and introduced the Butterfield band as a group that was purely imitative, asking 'would we put up with it anyway?' or something to that effect. It was a very offensive introduction, to the band and to all of us. And Butterfield came out and just blew everybody's socks off. I've got pictures of all of us -- Von Schmidt, Maria -- and our faces were just lit up. I'd never heard Chicago blues with so much drive. We were just totally flipped out."

Thousands, not hundreds, had shown up for the Butterfield set. Maria Muldaur also remembers well the shattering impact the performance had on everyone. "Most of the other acts had been original acoustic blues guys and some guys from our generation. And then out came the Butterfield Blues Band. Most of us had never heard anything like it. I'd listened to R&B radio growing up in New York, and I'd heard a bit of electric blues before, but I'd never heard such electrifying electric blues. The band just sizzled. They burned. They crunched. They just set us all on fire. There's a picture of me in Baby Let Me Follow You Down that shows me just flipping out! The music was so danceable. Butter was just burnin'. It just took all the music we loved so many notches higher on an energy level."

Grossman, who had decided the night before to manage the band, was irate over Lomax's introduction; he found him backstage and an argument led to blows between the two men. Dylan, always savvy to changing trends, immediately enlisted the band to rehearse a few numbers with him for his performance later that night. His amplified tunes were roundly booed by most members of the old folk "mafia" (including a livid Pete Seeger, who apparently brandished an ax and threatened to cut the power cables if they didn't drag Dylan off at once). They felt betrayed; only Theodore Bikel accepted what was happening.

But it was too late. These two performances -- by Dylan and Butterfield -- had sounded the death bell for the acoustic purity required by the folk establishment, splitting the Cambridge community in the process, with the younger, more open members no longer wary of embracing amplification or altering "purist tradition." Paul Rothchild's gut reaction to the Butterfield band was right. Another era in American music was beginning at Newport. In one fell swoop the growing folk movement, made so famous by this festival, began to unravel and would come to a grinding halt within three years.

The Cambridge scene would never be the same. And neither would the Newport Folk Festival. At Club 47, Jim Rooney began booking Chicago blues acts and "amplified music." Other clubs followed suit. Soon the area would become known as a great blues town. The next group of young stars to germinate there would include Peter Wolf, J. Geils, Tim Hardin, Taj Mahal and a young Bonnie Raitt.

![]()

By 1970 many of Cambridge's young inner circle had relocated to Woodstock, a small, rural community north of New York City on the edge of the mountains and Catskill Park. The Muldaurs had a home there. Jim Rooney had left Club 47 in 1967 to work for George Wein, but now he was there, too, as was former Kweskin band member Bill Keith. Even Dylan had a house nearby. Most were drawn there by the aura of Albert Grossman and the studio and offices he was building.

Butterfield was also a resident. By 1971 he had his first house, a new son and a taste of the family stability and happiness not possible during years on the road. But he had no band; his last large ensemble recently had dissolved, most of its members scattering to tour with Stevie Wonder and others or becoming involved in their own projects like Full Moon, the great Buzz Feiten/Gene Dinwiddie/Phillip Wilson group.

Butterfield was not alone -- Woodstock was becoming a town of solo artists (and solo wannabes), each often working on each other's projects, but there were few groups living there, the Band a significant exception. "Paul was one of the guys around," Geoff Muldaur remembers, "and we used him on the second album I did with Maria, and even on an Eric Von Schmidt recording done in Woodstock."

But with the demise of the big band, Muldaur feels like Paul was looking for a change. "That band had gotten bigger and crazier, and it was capable of generating some tremendous grooves, but I think after it ended Paul was looking for something very different."

Woodstock was a working musician's town. There wasn't much of a club scene (although there was a lot of jamming at musician's homes and studios), and most of the socializing was centered around drinking and hanging out nightly at places like Deanie's or the Joyous Lake.

Guitarist Amos Garrett had been there since 1970. He had come south from Canada with Ian & Sylvia and had been playing with the Muldaurs, who had a record deal with Warner Brothers and whose first album, Pottery Pie, had been a major critical success. After their second record however, Geoff and Maria separated. "At that time we -- Paul, Geoff and me -- were all basically unemployed and not involved in any sort of project," says Maria Muldaur. "My recollection is that Paul and Geoff and I were all hanging out at Deanie's. Albert may have been there too. And we all just decided to put a band together." If Grossman wasn't there, he was quick to give the project his blessing.

Unlike these three, all reaching the peak of their creative powers after years of playing, 19-year-old local Chris Parker was a newcomer of sorts; he had spent his years in Woodstock mostly playing with anyone who needed a drummer and had little road experience. But Butterfield heard something special. "Paul had come to see me at the Cafe Espresso, where I played with four different bands. There was a gospel band, R&B band, jazz band and country band; I played in a rock band at another club. He heard me play a lot of different styles." Butterfield felt Parker was a drummer who could fit with the eclectic likes of Garrett, Muldaur and himself. "When I first got in the band Paul and Geoff seemed to have the vision for what they wanted to do. They both had a lot of ideas, and they definitely knew there were things they didn't want to do -- the Butterfield blues band thing, the horn band, the Chicago thing, the jug band. Everyone wanted it to be very fresh. It had to be new and exciting for Paul and an outlet for Geoff."

To round out the band they first tried bassist

Rick Danko, a close friend of Butterfield. But his commitments

to the Band prevented joining. Then organist Merle Saunders and

bassist John Kahn were imported from the West Coast.

Kahn had

been playing in San Francisco with Bloomfield and Mark Naftalin,

and Saunders was a musical partner with Jerry Garcia. Parker recalls

that "Paul wanted that B-3 jazz sound with Merle, like

Jimmy Smith, under solos. And Kahn was totally into Ray Brown

and Milt Hinton and could lay that big fat sound on the bottom."

Kahn had

been playing in San Francisco with Bloomfield and Mark Naftalin,

and Saunders was a musical partner with Jerry Garcia. Parker recalls

that "Paul wanted that B-3 jazz sound with Merle, like

Jimmy Smith, under solos. And Kahn was totally into Ray Brown

and Milt Hinton and could lay that big fat sound on the bottom."

After a summer's worth of tours, however, Kahn and Saunders decided to return to the West Coast. But not before the band (minus Geoff Muldaur but with Maria) went into the studio in Los Angeles to record the soundtrack for the film Steelyard Blues, which starred then-counterculture figures Jane Fonda, Donald Sutherland, Howard Hesseman and Peter Boyle. Composed by Nick Gravenites, Bloomfield and Saunders, the songs feature some great playing and singing, and are noteworthy as the final recorded performances of Butterfield and Bloomfield playing together.

The departure of Saunders and Kahn would open the door for a new dynamic the band members had never expected.

![]()

Ronnie Barron is a New Orleans original. "I met Mac Rebennack when I was 15. I'd been aware of him since I was 12, and he had a good working band that played on the west side where I lived, in Algiers. New Orleans was a real fly-by-night town, where there was a big tourist crowd and people wanted to drink. They didn't care about the music that much, just wanted to be entertained. So I created my 'Reverend Ether' character, almost by accident. I made up this mythology about the voodoo and the gumbo. I'd shake the tambourine and say, 'I'm gonna drop the truth on you!' I made up all this shit. This was before I worked with Mac, when I was working in a club on Bourbon Street. He'd come in and kind of watch what I was doing. I had also written this song, 'Black Widow Spider,' that was part of the act. Mac realized the value in it, and after he hired me he wanted me to be the original Dr. John, because I already had a handle on the thing. Ahmet Ertegun and Jerry Wexler of Atlantic Records had been working with New Orleans' musicians for a long time, and they could see it too." But Barron went to California and gave Reverend Ether to Rebennack, who took the role and "Black Widow Spider" to develop his "Dr. John" persona.

Barron had been hand-picked in 1965 by Sonny and Cher for his playing and songwriting, and came to California to fulfill a dream -- to become a session player; he also was signed with Atlantic. "I didn't know who Ahmet Ertegun was, but he found me in California and used my group there -- the Prime Ministers -- as the back-up group on Bobby Darin's last sessions in 1966. The Prime Ministers were a combination of the Staple Singers, Imperials and Impressions, and we were pretty successful working the all-black clubs around L.A.; we signed a contract with Don Costa, Sonny & Cher's manager, at RCA, and recorded a bunch of singles for them."

Under contract as a session man, he began to find the work disappointing. "It wasn't till I got there that I realized how unfulfilling that work could be. All the music just went through me. There was no time to digest anything."

In 1968 Bennett Glotzer, then a partner of Grossman's, had told Barron he needed to hook up with Paul Butterfield. Barron had never heard of him. Two years later Barron found himself back in L.A., playing piano every day, working on songs and gigging at night. Dr. John brought Grossman to one of Barron's gigs, and they met. "I forgot all about him until later, when I got the phone call from him. It was a Thursday, and he said, 'I tell you what. I'd like for you to come and look at this thing I've got with Paul Butterfield. Can you fly to Woodstock tomorrow?' That was too soon, but I was there on Saturday."

![]()

Barron arrived in Woodstock on a dark, windy night. "It was remote, cold and creepy. I'm a city guy and it was this quaint little town. Then I'm being driven down this long dirt road, and I arrive at this villa in the middle of nowhere. It was Grossman's place."

Muldaur, Butterfield, Garrett and Parker were waiting. They had taken Grossman's word on Barron, but none of them knew or had heard him. This first meeting quickly became more like an audition, with Barron at the piano, exposing his stylistic range. It was a very bizarre, inauspicious meeting.

"I didn't like Geoff at first," says Barron. "He was telling me what style of piano I was playing each time. Then Bobby Charles showed up. He was friends with all of those guys and living up there. I'd had all of his records on Chess when I was a kid and knew all of the songs, but I'd never met him. We didn't like each other much at first either. And Paul came up and gave me some shit. I just picked him up over my head, and that shocked everybody there. I'm a street dude and don't take that stuff. I was going to throw him down, but just put him back down instead."

Also there and new to the band was 24-year-old bassist Billy Rich. "I knew Billy only by reputation," Parker remembers, "from his gigs with Taj Mahal and as one of the two great bass players from Omaha -- Bugsy Maugh and Billy Rich."

"I had been working with Taj, and we were living in Woodstock for a few months working on a double album," says Rich, "that's where I first met Butterfield and Amos, and I knew Maria. We'd get together and jam at the Joyous Lake. But I left there and moved back to Denver. Then they called me to come up." The band, now known as Better Days, had not found a bassist for their first album, and when Rich arrived he went directly into the studio. The first song chosen was "Highway 28."

"I'd never met Billy," Geoff Muldaur says, "and he did an overdub standing in the control room. And on went this fucking bass part -- go back and listen to it. We just couldn't believe it. And we looked at each other and said, 'Now we're there. Let's go.' "

"I don't know if anyone thought

it was going to work," Rich adds. "I think Paul and

Geoff and Ronnie knew what they wanted to do, but it just came

together. Once we got into the studio and started working stuff

out it really started to work well.

The band was kind of like

a democracy -- everyone wanted to be happy with what we

were doing to make it work. Everyone had a lot of input."

The band was kind of like

a democracy -- everyone wanted to be happy with what we

were doing to make it work. Everyone had a lot of input."

And everyone soon became friends as well, the band a harmonious group. Grossman's hunch about Barron proved right -- this "outsider," with his incredible voice and ability to play the many diverse styles emanating from New Orleans and elsewhere, won them over, at first with his studio work, injecting a deep, Southern groove and soulfulness, a new dynamic that had an exponential impact on the band's music.

"When Ronnie came it opened things up both stylistically and also on the performance level," Parker says. "He was very intent on performing and had a whole look and vibe and approach that he had been using -- he bent a little bit for us and we played some things that showcased him, just like we did for Amos and Geoff."

And then they won him over. Barron: "Geoff really helped me find myself again. For years playing as a session musician I couldn't be myself. When I got to Woodstock I still had that session mentality to play like people wanted me to, to sound like other people. But Geoff would say, "Don't play like the other guys -- play like you.' And then he turned me on to all kinds of music and I found out he really knew so much about music, even the New Orleans people. We all just became the best of buddies."

Like all Butterfield ensembles, there was constant rehearsing, often in studio so the band could analyze on the spot. All were aware that this was a gathering of immense talent; Bobby Charles, the author of "See You Later Alligator," Fats Domino's "Walkin' to New Orleans" and "It Keeps Raining," was the unofficial seventh member, contributing songs and even vocals. Unlike prior Butterfield groups, a young rhythm section backed four principals who were stars in their own right, creating a quintessential American band, melding a purely American mix of indigenous styles.

"It was definitely an adventurous band for the time," Garrett recalls. "It was definitely the furthest Paul ever got away from the Midwest, Chicago harmonica or horn band sound. That band was a very unique rhythm & blues band. It incorporated blues influences of Paul's, but it had an acoustic, Delta influence of Geoffrey's and a heavy New Orleans feel from Ronnie. My playing was just so strange; it kind of fit in everywhere, in every context. Plus the fact it had four vocalists. And everything was a group decision in terms of material, but we leaned toward new songs. We loved Bobby's writing in particular.'

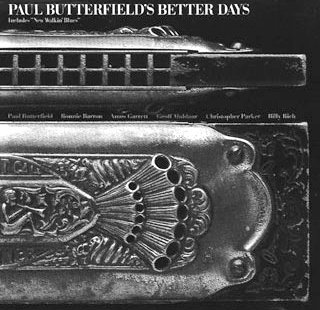

When Better Days arrived in record stores in 1972, the album cover was a model of democracy -- the names of the players were arranged alphabetically, in small type below the band's name (Butterfield had made a conscious decision to try to remove any allusions to his prior bands or emphasis on his name). Jim Rooney had written extensive liner notes and Kathy Butterfield had taken the pictures of six smiling band members.

Critical acclaim was quick to come, although

many reviewers had trouble pigeonholing the band into any one

category. For obvious reasons. Opening with "New Walkin

Blues," it's clear that Butterfield is making a statement

of difference by completely rearranging the song heard on East-West

-- with greater fealty to the original. Muldaur's

acoustic slide at counterpoint with Barron's organ, the

song modulating at volume and pace as Garrett jumps in with a

biting solo, followed by Barron's which feels completely

different but fits perfectly. Butterfield's vocal is mild

and restrained, and the guitars and organ seem to come together

to crescendo with and envelop his closing harp attack.

-- with greater fealty to the original. Muldaur's

acoustic slide at counterpoint with Barron's organ, the

song modulating at volume and pace as Garrett jumps in with a

biting solo, followed by Barron's which feels completely

different but fits perfectly. Butterfield's vocal is mild

and restrained, and the guitars and organ seem to come together

to crescendo with and envelop his closing harp attack.

The following cut, Percy Mayfield's "Please Send Me Someone to Love" is a blues a world away from Robert Johnson, a showcase for a beautiful, melancholy solo by Garrett and a gorgeous reading by Muldaur, whose vocal climaxes with a stunning falsetto. Barron's up next, with "Broke My Baby's Heart," self-penned, with another oblique Garrett effort, a tough one from Butterfield, and Barron's Southern-drenched vocal, wailing on the final chorus.

Bobby Charles' "Done a Lot of Wrong Things" is sad and sweet, with Muldaur and Butterfield providing some rich harmonizing and the latter a lovely harp solo. "Baby Please Don't Go" is acoustic and adds Maria Muldaur's voice and fiddle. It's not until "Buried Alive in the Blues" -- a Gravenites tune originally written for Janis Joplin just before her death -- that the band rocks, with Rich kicking in on the chorus, pumping the song forward. Then a tune by Muldaur's old friend Eric Von Schmidt, "Rule the Road" (with near-perfect acoustic accompaniment by Butterfield), Nina Simone's famous dirge "Nobody's Fault But Mine" and finally "Highway 28." On the latter Barron's barroom solo precedes Butterfield's, which ends with a screaming line that turns the beat around and double-times Rich's bass part. "Paul could punctuate the entire feel of something, with one lick, that would become the motif for everyone, establishing the rhythmic pattern for everyone," Muldaur says.

Twenty-five years after it was recorded, Better Days still sounds as fresh and new as it did when released. Butterfield had taken the blues in another direction -- this time with an eye toward songwriting, exposing the range of blues-as-song from writers of different locales and different eras, highlighting the great writing of Barron and Charles. And, of course, there was incredible playing and singing as well.

![]()

"When we moved to Woodstock Paul and Kathy lived off Route 212," Maria Muldaur recalls. "They had a great house in the country and were totally grooving on it. Geoffrey and I had just moved there -- this was in 1970 -- and there were all these killer bands camped out in various parts of the woods around Woodstock. The jam sessions were just phenomenal -- there was our band, Paul's band, the Band, Dylan and many others."

But Muldaur's connection to Butterfield was more than just a neighbor. "It was very special to me. Geoffrey was considered a great white blues singer who really studied Claude Jeter, the Swan Silvertones and all the great gospel singers, and he was a mentor to me. He had decided that my niche should be to sing sweet, bluesy, ragtime, jazzy tunes, and he always told me I was the reincarnation of Mildred Bailey, who was a great jazz singer with a high, lilting, swinging voice. But I'd been listening to blues singers and Mavis Staples, and that's what I felt inside and wanted to express -- that level of musical energy. But at the time I didn't have the background or the vocal chops and I wasn't born with a big, heavy blues voice. But that's how I wanted to express myself. So I was severely suppressed and discouraged from attempting to sing like Aretha or whomever.

"But we'd go over to Paul's house -- Kathy was pregnant with Lee at the time -- and we'd have dinner and sit around the piano and sing and jam; Paul and Geoffrey would mostly be playing tunes and exchanging ideas. At a certain point Kathy would have to go up to bed, and we'd be jamming away. But after she got upstairs she'd lower this little microphone through a grate in the ceiling and she'd turn a mic on and be recording us! The creative juices would be flowing far out to the night. And it was Butter that first encouraged me to let loose and just sing the blues. You know, Butter wasn't considered a fabulous vocalist, primarily just a great harp player. But when I listen now I realize he was a great blues singer, too. Even though he didn't have killer chops, he had the whole sensibility and musicality and approach down pat; it was as much in him vocally as it was in his harp playing.

"And he encouraged me just to sing out, not to worry about singing pretty or hitting all the right notes, and with his encouragement he just loosened me up. He loosened all the levels of self-consciousness and doubt out of me. I remember there was a song he and Kathy had started writing called 'Blind Leading the Blind,' where the lyric goes 'it was the blind leading the blind, when my baby and I drank wine,' and I remember us just drinking wine and sitting at the piano caterwauling away and singing the blues and letting it all come out, not worrying about crooning or hitting all the right notes. And he'll forever live in my heart for that and for respecting me as a fellow musician. I still have a picture of Paul in my office and think of him every day.

"I don't think I would have ever become a blues singer without the personal and loving encouragement from him. He just went for it and took it all in, and he embodied the essence of what the blues was all about. Unfortunately, he lived that way a little too much."

| This is an abridged version of the Butterfield article, which continues

through the disintegration of the Woodstock scene and the demise of Better Days.

For the complete article, get the hard-copy version of BLUES ACCESS. |

|

|