| ||

|

The Sacred Steel tradition

"And suddenly there came a sound from heaven as of a rushing mighty wind, and it filled all the houses where they were sitting."

Acts 2:2

The organ is a familiar sound in most American Protestant denominations. But not in the Keith and Jewel Dominions, both Holiness-Pentecostal churches where the primary accompanying instrument during worship services is the steel guitar.

It's a tradition that dates back almost 60 years, and though heard around the country, is especially strong in Florida congregations. Folklorist Robert Stone first heard about it from his friend Mike Stapleton, part-owner of the Banjo Shop in Hollywood, Florida, a specialty music store for string players of all stripes. "He said that black men were buying lap steels, and that they were playing them in church."

Indeed they are. When this style of accompaniment first sprang up before World War II, Hawaiian lap steels were more popular among guitarists than the fretted models. And while major manufacturers stopped making them in the United States years ago, they remain the instrument of choice for many guitarists, including Keith Dominion guitarist Willie Eason, who first played the steel in church in 1939. Others prefer the more complicated and elaborate pedal steel guitar, an important element of country music. But this is not island music, nor is it country; though it can incorporate both elements, it owes as much to its African-American heritage as either.

Stone, who was working in the folklife program for the Florida Department of State in 1991, was intrigued enough to check out some of the players. "I interviewed the Rev. Aubrey Ghent at his home, and that same day I went to a convention in Pompano Beach where Glenn Lee was playing."

Totally knocked out by the music and armed with a NEA folk arts program grant of $6800 and a couple digital recorders, Stone, recording engineer Bill Dudley and Stapleton headed out into central Florida, recording in private homes and at church services. From the best takes he produced 600 copies of a cassette of his field recordings, which sold out almost immediately.

The tape documents a functional music designed to accompany church services. Like the organ, the steel guitar, with its ability to vary the pitch of, or bend, notes and chords, is nicely suited to accompanying groups as well as creating an instrumental voice of its own. Players have to be light on their fingers, so to speak, to react to spontaneous situations as they happen: leading hymns; providing liturgical backgrounds; punching up the emotional level during "praise music" periods; heading processionals and recessionals and otherwise covering whenever needed for services that can last from three to five hours.

"I knew had something good," Stone explains. "I

had a digital master. So I pitched it to two places, Smithsonian

Folkways and Arhoolie, because I knew that they had international

distribution." Arhoolie's Chris Strachwitz, already familiar with

African-American

Pentecostal music, called Stone.

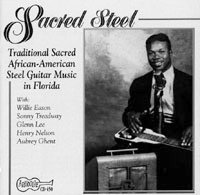

They collaborated on Sacred

Steel: Traditional Sacred African-American Steel Guitar Music

in Florida, an expanded version of the tape that Stone calls

"the tip of the iceberg," released on compact disc

this year.

They collaborated on Sacred

Steel: Traditional Sacred African-American Steel Guitar Music

in Florida, an expanded version of the tape that Stone calls

"the tip of the iceberg," released on compact disc

this year.

Sacred Steel opens with three-song sets from Treadway, Lee and Eason. All show eclectic influences that stretch the concept of traditional gospel music. Treadway's version of "Don't Let the Devil Ride" swings and bends a blues pattern just as his pedal steel quietly nudges and tantalizes the melodies of hymns like "In the Garden" and "At the Cross."

Glenn Lee's selections offer bits and pieces of Hawaiian and surf music, shadings of R&B and small-combo blues and country-western flourishes. Besides being a lovely hymn, in Lee's adept fingers, "Pass Me Not, Oh Gentle Savior" could have passed muster as the break number at a Hank Williams' concert. "Joyful Sounds" is the kind of sanctified dance music for which Van Morrison constantly strives. For wild rides like this, I'd be tempted to go back to church.

Still, nothing quite prepares you for Willie Eason's "Franklin D. Roosevelt, A Poor Man's Friend." Written soon after the president died in 1945, it's a careful, journalistic account of his passing and as heartfelt and sincere a eulogy as I've ever heard. When Eason sings, "It was sad about Roosevelt" and lets his instrument echo his words, the steel cries real tears.

There are also live recordings from services that emphasize the functionality of the music and the players' sharpened impromptu skills. During Treadway's "This Is a Holy Church," an example of "praise music" used to help fill the congregation with the Holy Spirit, the steel guitar sounds like an entire horn section, a veritable moving feast of improvisation. Elsewhere, the Rev. Ghent creates the tone of a solo voice, soaring high over the congregation and the other instruments during "God Be With You."

Essays on the churches themselves and their history and Stone's own extended notes on instrumentation and the players themselves help put the music in context. With so much rich history and a strong continuing tradition, Stone thinks there could be enough material for a book on the subject.

In May, Stone produced new albums for Aubrey Ghent, Sonny Treadway and Chuck Campbell with Chris Strachwitz during a whirlwind week that included some filming as well for a video documentary.

Stone is particularly enthusiastic about Campbell, who is from Rochester, N.Y., and is the first sacred steel guitarist he has recorded outside Florida. "No one's heard him yet. He's a real hot dog and has been called the Eddie Van Halen of steel guitar. His imitation of African-American vocals, melismas and slurs is incredible."

Perhaps the most encouraging point is that this is no museum curiosity; it's a living, breathing music, with new life being pumped into it every week. "There seems to be more interest among the players and the congregations than ever," Stone says. "There's a whole generation in their teens and twenties that just can't get enough, and players like Chuck Campbell play contemporary sounds that the younger players can relate to."

-- Leland Rucker

|

|