|

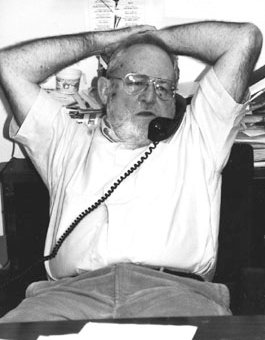

Shrink-wrapping albums must be about the least glamorous task

in the record business, but find Bob Koester on an average work

day and he's just as likely to be doing that as supervising

a recording session.

It's been a long time since Delmark Records was a one-man

operation and he had to do everything, but the dean of

Chicago blues and jazz recording still works a six-and-a-half-day

work week and continues to ungrudgingly perform what he calls

the "shit work" of the business. As someone who has

hand-built and kept afloat an independent label for more than

40 years, Koester knows well that success and survival require

close attention to the details. Or as he puts it, "I'm

not an employee, so no job is a menial task."

Koester doesn't get out to see live music as much as he

used to, but as someone who's been actively checking out

and recording the jazz and blues arena for the last five decades

he's got enough memories to supply an army of music fans.

The artists he has waxed over the years make up a real "Who's

Who" of the blues world: Magic Sam, Otis Rush, Roosevelt

Sykes, Jr. Wells, Buddy Guy, Robert Jr. Lockwood, Jimmy Dawkins,

J.B. Hutto, Big Joe Williams, Arthur "Big Boy" Crudup,

Carey Bell, Luther Allison, Yank Rachell, Sleepy John Estes, just

to name a few.

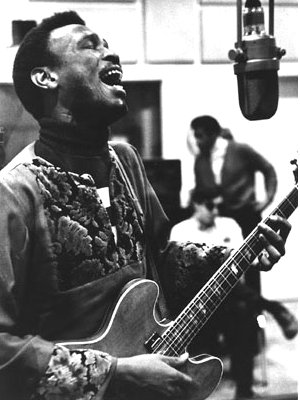

Magic Sam

On the jazz side, Delmark runs the spectrum;

its catalog -- equally as large as the blues catalog --

contains everything from vintage New Orleans jazz to pioneering

recordings of the '60s Chicago avant-garde movement.

Although many of the greats Koester has recorded have passed on

to blues heaven, he's not stuck on the "good old

days" -- there's still too much recording to

be done. Delmark has benefited from the recent blues resurgence

and has expanded both physically -- the Delmark House, with

its 24-track studio, was purchased five years ago -- and

in terms of its catalog, which is growing rapidly in both number

and diversity.

Since the purchase of the new studios on the North Side five years

ago, Delmark's rate of releases has increased dramatically,

and the annual output (including CD releases of catalog material)

now equals about what the label released in its first decade and

a half. Because of serious economic problems throughout the '80s,

a decade when Delmark released little new product, it has been

late in reissuing back catalog on CD. This process will soon be

complete, leaving that much more room available for new recordings.

Arthur "Big Boy" Crudup

Arthur "Big Boy" Crudup

The size of Delmark's staff has expanded to five full-time

workers, including Susan, Koester's wife of more than 30

years, who had worked part-time for the label for years before

hanging up her social-work job several years back, and Steve Wagner,

in-house producer and Delmark's manager since 1987. Koester

has put his full trust in Wagner to run the operations and points

to Wagner's management skills as one of the most important

elements to Delmark's success in recent years.

One of the main reasons for Delmark's ability to survive

as an independent label in a field which sees so many go under

-- aside from consistently high quality records and artists

-- is the downtown Jazz Record Mart (JRM),

which Koester acknowledges is his "bread and butter." Stocked with

perhaps the broadest range of jazz and blues compact discs anywhere,

the store also has a large selection of new vinyl, including Delmark's

back catalog as well as thousands purchased by Koester at bargain

rates following the introduction of the compact disc.

If there is a center to the blues scene in Chicago it is here,

at 8,000 square feet the "largest jazz and blues record

store in the world" and a mecca for out-of-town blues visitors.

The new location on Wabash Street is just around the corner from

the 7 and 11 West Grand Street locations that housed the JRM operation

(and Big Joe Williams, who lived in the basement at 7 West Grand)

since the early '60s. The new, modern facilities lack the

funky atmosphere of the last two locations, but after 40 years

of cramped working space, leaky roofs, damp basements and uneven

floors, Koester isn't sentimental about the change.

Over the years the JRM has served as a training ground for many

jazz and blues producers, writers and label owners, and in this

regard it is difficult to overestimate Koester's role in

shaping the last four decades of blues recording and documentation.

Living Blues magazine was started, with seed money from

Koester, in the basement of the JRM by a group that included employees

Amy van Singel, Bruce Iglauer and Paul Garon, while the Delmark

operation became the blueprint for how to run an independent label.

Blues label owners who got their start after having learned the

ropes from Koester as JRM employees include Iglauer, who recorded

his debut Hound Dog Taylor album for his Alligator label while

working at the Mart; the late Pete Welding of the Testament label;

Don Kent of Mamlish; the late Bruce Kaplan of Flying Fish; Pete

Crawford of Red Beans; Amy van Singel of Rooster Blues and Michael

Frank, whose Earwig label perhaps most closely follows Koester's

tradition of recording older, less-commercially viable artists.

Last year Koester's role as a mentor and pioneer in the

independent record business was formally recognized when he was

elected into the Blues Foundation's Blues Hall of Fame.

Koester accepts 1996 Handy Award

|

|

The history of Delmark Records

stretches back to 1953, when Koester

began selling jazz 78s by mail from his college dormitory room

in St. Louis, but he traces his lifelong passion for jazz and

blues back to a live radio broadcast of Fats Waller he heard as

an 11-year-old in Wichita, Kansas. The young Koester was soon

haunting local record bins and seeking out the occasional live

show, and among the acts he recalls with enthusiasm are the Count

Basie Orchestra with Jimmy Rushing, Lonnie Johnson and the Lionel

Hampton Orchestra, whom he caught several times at a hall where

whites had to sit in the balcony.

His budding passion for records soon led him beyond the record

stores to jukebox distributors and second-hand shops, as well

as to "junking" for used 78s in Wichita's

black neighborhoods. Like other jazz enthusiasts of the time,

Koester regarded blues as a sub-category of jazz and collected

a wide range of music, but he also attributes his emerging eclectic

taste to the relative scarceness of records in town. "If

you lived in Wichita and it was black and secular, you bought

it."

In 1951 Koester left for St. Louis University to prepare for a

career in cinematography, but his life-course was changed by the

city's vibrant live music environment and wealth of used

records.

"St Louis was a fucking gold mine," he recalls. "I

had a route every night. After my last class I would hit the second-hand

stores. After the first year Ron [Fister] and I started this little

record store [K&F Sales] right off the campus. We found this

little tiny place for 40 bucks a month. But it was closed in the

afternoon while I was around hittin' my route."

In 1953 Koester made his recording debut with a 10-inch by a local

trad jazz band, christening his label Delmar after the swinging

street in town bearing that name (the "k" was added

later due to trademark problems). In describing his inspiration

for his operation, Koester points out that the formula is obvious.

"It came from Commodore, a record store that taps the till

to do record dates. It's an old classic formula: Keynote,

Musicraft, Commodore, Prestige."

Koester also began his career as an activist for jazz and blues

in St. Louis, promoting concerts by local artists and publishing

a short-lived magazine, The St Louis Jazz Report, whose

first issue features a shot of a young Little Mac Simmons playing

with Robert Nighthawk at East St. Louis' Red Arrow Inn.

Koester's eventual move to Chicago was prompted through

a trip he made there in 1958 to buy masters, but which resulted

instead in his purchase of Seymour's Jazz Mart and becoming

an advocate for the Chicago scene. The recordings of Speckled

Red and Williams were not released until the early '60s,

when Delmark began its Roots of Jazz blues series. New material

for the series included the debut revival recordings of Sleepy

John Estes and Yank Rachell, who Koester had helped locate in

Brownsville, Tennessee.

Ironically, Estes' brother worked in a store next to Koester's

first Chicago location, something which he only learned after

he first brought the bluesman to Chicago. Although he had noted

the brother's last name before, Koester never seriously

considered the idea that they might be related and suggests that

if he had only once jokingly called the man "Sleepy"

he might have found the Brownsville blues crew years earlier.

The name of the series -- Roots of Jazz -- reflects

Koester's continual emphasis of the close relation between

jazz and blues and, more generally, the time of Delmark's

founding. A white audience for the music barely existed when Koester

began releasing blues. "We've never pretended we're

selling [blues] to a black audience," he readily admits.

Initially, the intended market was jazz fans interested in the

music's history and folkies who bought the few folk blues

records available on labels such as Folkways. Again, Delmark can

be seen as similar to Prestige and Riverside, jazz labels which

started blues series in the very first years of the blues revival.

Koester was pleasantly surprised by the relative success of the

first acoustic blues records but disappointed with the relative

lack of attention folkies gave older blues artists during the

'60s folk revival. As he remembers, "1964 was the

year that the folk infrastructure paid lip service to blues, then

they went on to protest. The people who operated the folk infrastructure

were very interested in protest, and when they found out that

blues singers generally didn't do that much protesting

-- that they were more interested in talking about sex --

they kind of disdained the whole blues thing.

"I remember having folk music concerts downstairs from

that great icon of the folk planetary system, the Old Town School

of Folk Music. I couldn't get 'em to come in free

to hear Big Joe Williams. They were up there talking about Big

Bill and Leadbelly, and they wouldn't go downstairs to

listen to Big Joe or Sleepy John."

After 10 records of older artists, Delmark made an abrupt change

in 1965, releasing Jr. Wells' classic Hoodoo Man Blues,

with Buddy Guy on guitar. Hoodoo Man was the first full-length,

studio album of a working electric Chicago blues band and presented

a much more contemporary portrait of Chicago blues activity than

the handful of electric blues LPs then available, which were largely

collections of previously released singles.

As when he first released a country blues record, Koester was

uncertain whether there was an audience for such a record. "I

thought of the Jr. Wells record as kind of a daring thing, paying

extra sidemen and music that the folkies wouldn't like.

But I guess they were a little ahead of me. I mean, I was selling

Muddy Waters and Howlin' Wolf records to young white kids,

but most of 'em were wishing that the bass player and drummer

were absent so that they could hear Wolf's guitar licks."

The Wells LP signaled a new direction for Delmark. Prior to Hoodoo

Man Blues, the West Side style was scarce known to the white

public, and over the next number of years Koester introduced Wells'

Cobra Records labelmates Magic Sam and Otis Rush as well as the

debuts of Luther Allison, Jimmy Dawkins and Carey Bell. The trend

continues today, with the acclaimed recent debut album from Jimmy

Burns.

Koester's approach to blues from a jazz background is reflected

in the breadth of Delmark's catalog, his use of Delmark

jazz artists as blues horn arrangers and in his championing of

blues piano and stand-up vocalists. He explains his own attachment

to blues piano and the blues more generally in generational terms:

"[For] most of the jazz fans of the '40s who got

interested in blues it was one of two things: They bought a Bessie

Smith record because Louie Armstrong or Joe Smith was on it or

a Pinetop Smith record because you liked boogie-woogie. And we

were really more interested in piano than we were guitar.

"One thing that really bugs me about whitey's approach

to the blues, and it's not totally a racial thing, is the

failure to accept and listen to blues piano. You really haven't

come to grips with blues until you can appreciate Peetie Wheatstraw,

Walter Davis and Dr. Clayton. They are vitally important artists.

And the reason nobody appreciates it is that nobody is listening

to the lyrics; we're all looking for guitar licks. That's

why we don't buy piano records, which I find appalling."

Koester is just as outspoken on the primacy of vocals in blues.

"Although it's nice to have whites out there buying

our records, they often miss the point of the whole exercise.

Blues is a verbal and vocal music, and they act like they were

at the opera and were expected to listen to the orchestra more

than the singing."

Needless to say, Koester is not one to chase the latest trend

in the market. He disdains those who cater to contemporary fans'

preference for "stinging" electric guitar blues.

Or as he expresses his business philosophy in his typical blunt

manner: "I record what I fucking want to, and then I try

to find a market for it ... I don't record somebody

cause I think they're gonna be popular this year. I don't

really look at the market when I decide to record. Very few jazz

labels do. If that were the case, Blue Note never would have opened

their doors."

|

|