| ||

|

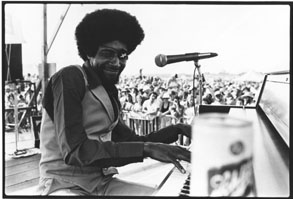

"Booker come off the piano, it got fire jumpin'

off of it. Completely. Fi-yah. Just one of them things."

-- Ernie K. Doe

The New Orleans Jazz & Heritage Festival, for the uninitiated, has a lot in common with Chaos Theory. It throws so much at you that unexpected patterns and themes eventually appear out of the gumbo. This year's leitmotif involved the late Piano Prince of New Orleans.

Ask most knowledgeable music fans to name a great New Orleans piano player and they could probably come up with Jelly Roll Morton, Champion Jack Dupree, Tuts Washington, Professor Longhair, Fats Domino, Dr. John, Allen Toussaint or, if their reference is more contemporary, Harry Connick Jr., Davell Crawford, Jon Cleary or David Torkanowsky. Ask a musician from that city the same question and the first name they are likely to respond with is James Carroll Booker III.

Case in point: It's the opening day of JazzFest, and we're crammed into the Music Heritage Stage, which is in reality a stable at the festival's racetrack setting. The first of numerous downpours that weekend is about to begin. Onstage, each at his own piano, are an extraordinarily fit looking Dr. John and the always dapper Mr. Toussaint. Despite an interviewer who doesn't know when to get out of the way and let the principals ramble, they are both obviously pleased to be there discussing, in words and music, the irascible man of many monikers, James Booker. For more than an hour these musical giants treat us to the tales and tunes of the wildly erratic man they both loved and regarded as a genius.

A few days later I'm hanging out at WWOZ's on-site trailer where the station is doing livecasts from the fest, when producer David Kunian says, "Here, I want you to have these." "These" turned out to be a pair of CDs containing his 1996 production for radio, "The Life, Music and Mystique of the Bayou Maharajah," featuring lots of expressive interviews with Booker's friends and fellow musicians.

So I guess it shouldn't be a surprise that when I was perusing the rack of local music CDs at Louisiana Music Factory in the French Quarter, what should jump out at me but Gonzo: More Than All the 45s (on the Night Train International label)? It was a collection I'd never seen before of Booker's "rare and previously unreissued recordings, 1954-1962." (Not completely true: "Gonzo" -- Booker's only single to make the national R&B charts -- appeared on MCA's 1992 Duke-Peacock's Greatest Hits. The song's title, which was also one of Booker's nicknames, came from a dope-dealing character in the film The Pusher. Along with "Cool Turkey," "Smacksie" and "Junco Partner" it is one of the numerous overt references to heroin in his repertoire.) For someone so highly regarded, Booker's recorded output is relatively meager, and I was quick to jump all over this one.

To bring you up to speed: James Booker was born in 1939. He was a child prodigy who began taking classical piano lessons at age six. When he was 14, pianist Edward Frank got him an audition with Imperial Records producer and arranger Dave Bartholomew (the man behind all those great Fats Domino records). That meeting turned into a single on Imperial, "Doing the Hambone" b/w "Thinking About My Baby." James went on to play piano and organ at Cosimo Matassa's studio (the "Cosmo's Factory" of Creedence Clearwater Revival fame). He soon became a first-rate organist and recorded "Teenage Rock" in 1957 with the backing of great R&B vets Alvin "Red" Tyler, Lee Allen and Charles Williams.

It was around this time that Booker went on the road with Huey

"Piano" Smith and the Clowns, who had scored hits

with songs like "Dontcha Just Know It," "High

Blood Pressure" and "Rockin' Pneumonia and

the Boogie Woogie Flu." Smith, however, had an aversion

to touring and Booker was sent out to impersonate him,

which -- musically at least -- was no problem for

the "Music Magnifico."

with songs like "Dontcha Just Know It," "High

Blood Pressure" and "Rockin' Pneumonia and

the Boogie Woogie Flu." Smith, however, had an aversion

to touring and Booker was sent out to impersonate him,

which -- musically at least -- was no problem for

the "Music Magnifico."

Booker was straight out of the whorehouse piano tradition, where you had to be able to play anything from pop tunes to all kinds of classical music to jazz. The songs on his recordings include Chopin's "Minute Waltz" (recast as "Black Minute Waltz"), "Eleanor Rigby," "Swedish Rhapsody," "King of the Road," "Malague-a," "Over the Rainbow," Ernesto Lecuona's "Gitanarias," "He's Got the Whole World in His Hands," Lead Belly's "Goodnight Irene" and, of course, plenty of funky New Orleans R&B.

This versatility stood him in good stead on tours and in the recording studio with Lloyd Price, King Curtis, B.B. King, Aretha Franklin, Ray Charles, Otis Rush, Freddy King, Lionel Hampton, Joe Tex and Fats Domino (that's Booker playing piano on Fats' 1959 hit record, "I'm Ready"). In the 1970s, he expanded his scope to sessions with Ringo Starr, Geoff and Maria Muldaur, Jerry Garcia, T-Bone Walker and the Doobie Brothers.

Booker's problems with drugs started early, too. He was hit by a speeding ambulance at age 10 and introduced to morphine during his recovery. He was still in his teens when he became seriously involved with narcotics. Booker told Jeff Hannusch (in Hannusch's excellent book I Hear You Knockin': The Sound of New Orleans Rhythm and Blues), "I was frustrated and started shooting dope as a form of rebellion. I was playing music so I could get enough money to buy dope."

Eventually, no Booker performance was complete without a version of the song that Dr. John describes as "Booker's anthem": "Junco Partner."

Down the road, down the road, come a junco partner

He was loaded as can be

He was knocked-out, knocked-out loaded

And he was singin' this song to me

He said six months ain't no sentence

And one year, one year ain't no time

I know boys down in Angola

Servin' one year to ninety-nine

If I had a million dollars

Let me tell you what I would do

I would buy land around Angola

And grow a nice weed farm 'til 1992

I want whiskey when I'm thirsty

I want a little water when I'm dry

I want my lover when I'm lonely

And a little heroin just before I die

... and a little cocaine on the side

Now, popular musical history is replete with brilliant, smacked-out musicians -- Charlie Parker, Garcia, Chet Baker are just a few that come quickly to mind -- but Booker is one of the most wacked-out as well. In our Spring 1994 issue, we published a 1981 David Feld interview with the gonzo one that flirted with coherence in the same way his hands skittered about the keyboard.

This is the same guy who studied yoga while he was in Angola State Prison on a dope charge. When a guard spied him doing a head stand, Booker told him he was proving that he could do his time standing on his head.

Another doping buddy told Kunian that during a show at the legendary Dew Drop Inn, Booker motioned him to come around behind the piano. There the pal saw a string of joints laid out between each of the black keys ... with a syringe at the end of the keyboard. Booker was laughing and smoking one of the doobies the whole time.

But also evident in the words of many people Kunian interviewed is that, while he could act totally bizarre, "Little Booker" was an intelligent and very sensitive soul who retreated into drugs and drink when he could no longer deal with life's hardships. His habits were only exacerbated by a manic-depressive type of mental illness. You just know that Booker's behavior must have driven each of these compadres nuts at some point, yet they all speak of him in loving terms.

Russell Rock was the manager of the Toulouse Theater and a friend of Booker's: "There's no one in the New Orleans music community you could compare to that was so explosively both brilliant on his instrument and unpredictable in his emotions, who could do things that he wouldn't even know what he was doing. So as a consequence it was very exciting to hear him, it was a very emotional experience, it took you out of wherever you were and placed you very much present, which is of course the reason why you go to hear live entertainment. It was a thrilling experience."

Paranoid, his body ravaged by years of abuse, James Booker died November 8, 1983, at New Orleans Charity Hospital. It was a place he knew all too well, his landing place from too many seizures and breakdowns.

It was a wet and steamy JazzFest this year. Every once in a while, through the overcast and mist, a ray of light would shine through and raise a glint from what could have been a starry eye-patch. Half-glimpsed, ducking around the corner of a tent was what might have been the Bayou Maharajah. Then, with a smile and a cackle, he'd be gone.

Blues from the Red Rooster Lounge originates on Boulder's KBCO 97.3 FM (where it can be heard Sundays at 9 p.m.) and airs weekly on 15 radio stations around the U.S.. Check with your local station for availability. (Station program directors can receive a sample copy of the program by calling the Longhorn Radio Network at 1-800-457-6576.) The Rooster also consults for the MusicChoice digital cable radio service, a 24-hour commercial-free, all-blues channel available from hundreds of cable providers nationwide.

|

|