The Final Note

by Tom Ellis III

| Paul Butterfield The Final Note by Tom Ellis III |

The Final Years

Every day I grew blinder.

Thought I was strong,

Didn't need nobody.

But the strongest river

It can't flow up hill.--Paul Butterfield,

"In My Own Dream"

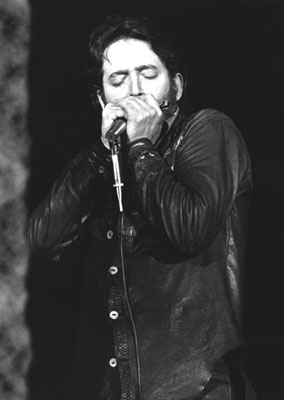

![]() y the time Ian Kimmet arrived in the States, Paul Butterfield's

career appeared to have gone solo for good; the days of his last

great band, Better Days, were far behind. Albert Grossman was

bringing Kimmet from his home in England, after a long business

relationship there, to be the head of A&R for his Bearsville

record label and to take over the day-to-day management of Butterfield.

Hopefully this would get his career moving forward again.

y the time Ian Kimmet arrived in the States, Paul Butterfield's

career appeared to have gone solo for good; the days of his last

great band, Better Days, were far behind. Albert Grossman was

bringing Kimmet from his home in England, after a long business

relationship there, to be the head of A&R for his Bearsville

record label and to take over the day-to-day management of Butterfield.

Hopefully this would get his career moving forward again.

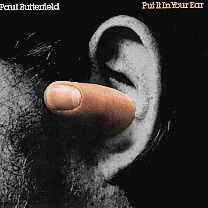

Kimmet came to in Woodstock not long after Butterfield had released his first solo LP, Put It in Your Ear, a 1975 effort that had featured a host of Woodstock friends like Garth Hudson, Fred Carter, Levon Helm, Chris Parker and Ben Keith, as well as New York City studio aces Gordon Edwards, David Sanborn, Bernard Purdie and Eric Gale. Legendary bassists Chuck Rainey and Motown's James Jamerson were also part of the sessions.

Overseeing it all, and acting as composer on four of the ten cuts, was one of the more important figures in the history of American pop recording -- Henry Glover. The first black record executive in America, Glover had helped Syd Nathan build Cincinnati's King Records into the country's first great independent label. While there he had produced early sessions by James Brown, Little Willie John and Hank Ballard. He was also the author of "Honky Tonk" and a string of songs that became both regional and national hits; his blues composition "Drown in My Own Tears" remains one of Ray Charles' greatest blues numbers. Glover was an A&R man of long pedigree who had also worked with Sonny Stitt and singers Sarah Vaughan and Dinah Washington after relocating to New York City.

Another Glover client was Levon Helm, who had first met the producer while he was a member of Ronnie Hawkins' band in 1959. The two had developed a fast friendship and four years later Glover would oversee the first recording by Hawkins' back-up group, urge them to go out on their own and later release one of their first singles as The Canadian Squires. They did leave Hawkins and by 1965 they were backing up Bob Dylan. By 1967 they had become the Band.

Helm brought Glover to Woodstock in 1975 as his partner in his first recording venture -- RCO Productions. But he had taken on Butterfield's LP for Bearsville and the supporting line-up made for a big budget affair. Although it wasn't the first time Butterfield had worked with an iconic producer -- Paul Rothchild and Jerry Ragovoy had overseen earlier albums -- he was clearly impressed with Glover. "I remember quite clearly the first time I was with Paul, in a bar in Woodstock, and he was looking me right in the eyes and asked, 'You didn't like my record with Henry Glover? Do you know who Henry Glover is?' " Kimmet recalls.

It was Kimmet's first meeting with Butterfield, and he'd heard the album before leaving London. In fact, he didn't like it and he was forthright with Butterfield regarding the reasons. "He said to me, 'Why don't my records sell over in Europe?,' and I answered quite clearly that nobody was getting a buzz over them. He laughed at my terminology. I told him that I thought he needed better material, and I told him I thought the record just wasn't enough. He was clearly amused by all of my comments."

Put It in Your Ear was the effort of a Butterfield who

wanted to chart a course very different from all of his preceding

works. There was a more mature sound to the album and Butterfield

was clearly treading on new ground, this time actively trying

to reassert himself as a vocalist, with mixed results. On songs

like "The Breadline" and "I Don't Wanna Go"

he finds his niche, and the former features some plaintive harp

playing that's evocative of the lyrics' social commentary. But

his vocal efforts fall flat on "If I Never Sing My Song"

and "Watch 'Em Tell a Lie"; he hadn't lived in these

tunes and their complex chord changes long enough to get the feel

down, or achieve a strong vocal presence, and neither has the

bluesy feel that always worked best for him. The charts are excellent

and the arrangements on some of the cuts are terrific, but all-in-all

Put It in Your Ear comes across as a mixed bag. And there's

just not enough harp playing. Critical reaction indicated a lot

of confusion. What should have been a musical event -- the first

solo album by one of the great American bluesmen -- fell flat.

It would be years before another Butterfield album would arrive.

was clearly treading on new ground, this time actively trying

to reassert himself as a vocalist, with mixed results. On songs

like "The Breadline" and "I Don't Wanna Go"

he finds his niche, and the former features some plaintive harp

playing that's evocative of the lyrics' social commentary. But

his vocal efforts fall flat on "If I Never Sing My Song"

and "Watch 'Em Tell a Lie"; he hadn't lived in these

tunes and their complex chord changes long enough to get the feel

down, or achieve a strong vocal presence, and neither has the

bluesy feel that always worked best for him. The charts are excellent

and the arrangements on some of the cuts are terrific, but all-in-all

Put It in Your Ear comes across as a mixed bag. And there's

just not enough harp playing. Critical reaction indicated a lot

of confusion. What should have been a musical event -- the first

solo album by one of the great American bluesmen -- fell flat.

It would be years before another Butterfield album would arrive.

Muddy Redux

RCO Productions gave Levon Helm a chance to record his idols. As a boy he'd worshipped blues artists and had personal experiences in Helena, Arkansas, watching his hero Sonny Boy Williamson II perform on the "King Biscuit Time" radio show with friends like Robert Jr. Lockwood, Memphis Slim or Robert Nighthawk. He'd sought out blues artists from then on, to listen and learn. So it was natural that Levon would want someone like Muddy Waters for the first RCO effort.

Muddy arrived in February 1975, with bandmates Pinetop Perkins and Bob Margolin in tow. Although he was friends with Helm and the members of the Band, it was the presence of Butterfield that comforted him the most; their last recorded collaboration had produced Fathers & Sons, an album Muddy considered one of his best since his halcyon period in the 1950s.

"Before Paul moved to Woodstock he was still in the 'legend' category for me," Helm remembers. "I made it my business to drive through Chicago on the way from Toronto to Tulsa every time we were ready to start the spring season of fraternity dances and tours in Oklahoma, Arkansas, Texas and such. Being from the Delta myself, I had to hear that harmonica -- I had to hear it. People had told me that Paul was the real thing, but I had to see it for myself. I'm kind of hard on the sound of harp players. If it doesn't sound like Jr. Parker or Little Walter or Sonny Boy, or respectfully aim at those qualities, I notice. It's like a phony Southern accent in a movie -- it bothers me a great deal. So I couldn't wait to get there and hear him.

"It was when he had Elvin on guitar, Jerome Arnold and Sam Lay, one of the best drummers a harmonica player could have; nobody can hit those triplets and then bust it wide open like Sammy can. With those four pieces Butterfield did all the singing and played all the solos, and every time he'd get through with a few verses Sam would hit those triplets and start the build-up, and here'd come Butter just screaming. I patted myself on the back just for taking the time to make the trip. Bloomfield had taken me to see him and we also saw Howlin' Wolf that night. The next night I saw his first set again before leaving. I met Paul, too. I just had a real good feeling about Chicago, too."

He wouldn't see Butterfield for two or three years, and rarely afterwards until both had moved to Woodstock. "From that first meeting on he was my favorite right on through -- he was one of the best harp players alive, no doubt about it. I heard him play where he reminded me of Sonny Boy or Jr. Parker or Little Walter, but at the same time he didn't sound like them. He sounded like Paul Butterfield. What a touch he had. He could hit a single note and make it sound like a full orchestra!

"We started hanging out after he moved to Woodstock. We were neighbors and naturally started hanging out because we liked each other. He was with Elizabeth Barraclough then, and 'The Last Waltz' was about to happen and Henry was bringing Muddy to Woodstock and we were cutting the album. We were really having a lot of fun. With Henry Glover as your A&R man and getting to play with Butter and Garth Hudson, well, it doesn't get much better."

Glover had graduated from Wayne State with a music degree and played first trumpet with big bands in the Northeast, including Louis Jordan's group. He was also a superb arranger. He'd moved to New York after his successful stint with King to become head A&R man for Roulette and had recorded Ronnie Hawkins and the Hawks when Helm was the drummer. Like Helm, he was also from Arkansas.

"Henry hooked up Garth and Paul on Muddy's album. Instead of having a horn section, Henry transposed it all down and Garth and Paul played the horn parts on harmonica and accordion. It was so nice. Then when Howard Johnson added one saxophone it sounds like a big section. And it all happened in three days. That was Henry Glover. Everybody thought so much of him and wanted to play good for him.

"But Paul had the long relationship with Muddy. That's why Muddy was so comfortable coming up to Woodstock. I'm sure his hot idea when he woke up in the morning wasn't to go find a bunch of white boys to play with! But with Butter being here it gave Muddy confidence that there were some players up here. If Paul was playing with them they had to be alright."

The Muddy Waters Woodstock Album was a complete success.

Muddy sounds as relaxed as he had in years and is obviously enjoying

himself. Everyone plays well, but Butterfield's playing is clearly

inspired (as is Hudson's) and his work on the slower numbers showcases

his deep blues pedigree. Muddy's exuberance, and that of the entire

ensemble, is especially evident on "Caldonia" and "Kansas

City," and Butterfield shows some great chordal work on both.

Muddy would soon add these two songs to his performance set list.

"In my opinion Henry Glover helped Paul realize that stature

of being a master soloist. Right in there with Yehudi Menuhin

and Louis Armstrong and those type of musicians, as a musician

on his instrument -- the harmonica," says Helm. "Henry

helped him reach the stature of the upper echelon of musicians.

His playing on the Muddy album is a good example. When he would

play for Henry he flew. He got the landing gear up and went subsonic.

He could really take you someplace when he would blow. It was

utopia for me, because being from the Delta I love good harmonica

playing -- I think you can hear more human touch in the harmonica

than any other instrument."

inspired (as is Hudson's) and his work on the slower numbers showcases

his deep blues pedigree. Muddy's exuberance, and that of the entire

ensemble, is especially evident on "Caldonia" and "Kansas

City," and Butterfield shows some great chordal work on both.

Muddy would soon add these two songs to his performance set list.

"In my opinion Henry Glover helped Paul realize that stature

of being a master soloist. Right in there with Yehudi Menuhin

and Louis Armstrong and those type of musicians, as a musician

on his instrument -- the harmonica," says Helm. "Henry

helped him reach the stature of the upper echelon of musicians.

His playing on the Muddy album is a good example. When he would

play for Henry he flew. He got the landing gear up and went subsonic.

He could really take you someplace when he would blow. It was

utopia for me, because being from the Delta I love good harmonica

playing -- I think you can hear more human touch in the harmonica

than any other instrument."

Before he left town Muddy was given the key to the city and more than 200 Woodstock residents showed up for the presentation. He was clearly touched. Later that year The Muddy Waters Woodstock Album -- the last Chess LP ever released -- won a Grammy, Muddy's first and only. RCO was clearly off to a prestigious start.

Sittin' In

Paul Butterfield had a wry sense of humor. In 1976 he and Elizabeth Barraclough joined host Andy Robinson for "Blues Break," a popular show on Woodstock station WDST-FM. As the visiting DJs they brought their own music for the broadcast. After a short introduction, Robinson turned it over to his guests. Butterfield's first song introduction and dedication went as follows: "When I heard we were going to spin records tonight I got very, very excited. I brought this particular Sonny Boy Williamson tune, called 'Help Me,' and I want to send this out to all my friends in Woodstock."

Friends from there and elsewhere hadn't forgotten Butter; he was doing a lot of session work for them and others over the next few years. There was some great obligatio playing -- some of it on albums by guys like Woodstock residents Nick Jameson, the Fabulous Rhinestones and Barraclough, as well as Levon Helm's RCO Allstars, which included Booker T, Steve Cropper, Duck Dunn and Dr. John, among others, along with producer Henry Glover. There was his stunning performance and playing at the Band's final, filmed/recorded appearance, The Last Waltz.

He was also still touring, on a limited basis. In 1976 he went out with a group that included Dallas Taylor and Goldie McJohn, as well as Rick Reed, a young bass player who Butterfield took under his wing. (At least one date from this tour was recorded and captured on video, although neither have yet been released.) They did a number of dates in the South, one of the first times he'd been there since his self-imposed ban of Southern dates following the assassination of Martin Luther King. "Paul was very patient with me, both on that tour and the next time we went out," Reed says. "His playing was just beyond belief and he was always pushing us to another level. And he was in great voice." (Twenty years later Reed would hold down the bass chair with William Clarke, a player who held Butterfield in great esteem and whom many thought was taking the instrument another step, just as Butterfield did, before his untimely death last year.)

Bonnie Raitt was another friend who called. "I didn't know Paul real well, but we did open shows for him and he did some session work for me on some of my songs. And we'd done a PBS show with Better Days. Paul was a legend -- great harp player, singer and band leader. He came to play on my 1979 record The Glow, on a Mary Wells song, "Bye Bye Baby." He came in and set up to play a couple of warm-up passes, which we cut live, to get ready to play his solo. He played it once -- never having heard the song before -- and we sent him home. He just nailed it!"

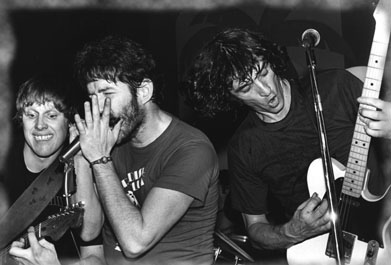

There were also reunions of the first Butterfield band -- gathering Bloomfield, Bishop, et al (usually without Jerome Arnold, Sam Lay or Billy Davenport) -- in the Bay area, although these events rarely captured the essence or magic of the old group. They did, however, allow Butterfield and Bloomfield to see each other. One of the final gatherings, at the Greek Theatre in 1978, showcased some fierce Bloomfield slide playing, but most were unrehearsed performances of band and blues standards.

But as the '70s wound down, Butterfield seemed even further removed from the active music scene, even that of the smaller clubs, although his playing ability had clearly not fallen into desuetude. "Paul seemed asleep," Kimmet recalls saying at the time. The end of the decade would bring a conflagration of events that would alter any apparent somnambulism.

Reawakening

In 1979 Elizabeth Barraclough went to Memphis to record an album with Willie Mitchell, the legendary producer who had guided Al Green through a series of giant hits earlier in the decade. Kimmet was working with Barraclough and remembers that her interests in "Memphis Soul" had grown significantly after her first Bearsville recording, and with Albert Grossman's blessing they flew to Memphis and met Mitchell. "He was totally into it and a terrific guy from the start, and we made a record there," Barraclough recalls. "Willie also made some trips to see us in Woodstock, and we used his back-up singers on some television shows like 'Midnight Special.' So we were developing a good friendship with him."

Barraclough was Butterfield's girlfriend, and she returned from Memphis thinking a Mitchell-Butterfield combination would result in a good album. "So Paul and Elizabeth went down to Memphis and Willie assembled his studio guys, including Michael Toles who was the guitar player and session leader. And the Hodges brothers and Memphis Horns would come around, and Paul knew of them. He fit right in with these guys."

It was an intriguing combination. But as with his first solo album, a lack of quality material hampered things from the start. "It would have been nice to say to Paul and Albert, 'Let's wait a year and get some good tunes together,' but it never was," Barraclough continues. "Albert was always ready to go with an artist if he said he had the songs together, so he let Paul. I would later learn from other A&R guys that stopping projects for lack of material wasn't that uncommon, and I would do it myself with some projects at Bearsville. But Albert's final word was often, 'I don't care -- let them make the record. And if it doesn't work out, well, whatever. If that's what Paul wants, let him make the record.' We'd had a few disasters with Paul that we had to shut down, but the Memphis thing got made anyway."

I remember buying the album -- North-South -- when it came out and wondering myself what was happening. The cover sports a shot of Butter blowing, but things within are quite different. It's thick with synthesizers, and there's an airy quality resulting from some of the tunes which are pure fluff. Butter sings well, but again there's not much harp, the exception being the instrumental "Bread and Butterfield." And on "Baby Blue" you can hear all of the old magic -- it's a masterful tune and indicative of the depth of feeling he could raise up -- in both his playing and singing. But the album stiffed; it was his last on Bearsville.

Although another had been planned. Before the recording of North-South, Butterfield had also been offered a chance to perform at Rockpalast, a German venue that featured American artists in concert. The shows were taped and filmed for broadcast; this one would also feature Ten Years After. "Paul was very stimulated by the idea of Europe and television and he had talked to Buzzy Feiten recently," says Kemmit. "So I called Buzzy about putting a band together -- it included Bobby Vega, Ernest Carter and Peter Atanazoff -- and he said he'd do it 'for the old man.' Paul said he wanted to do it, so we put it together and I went over as tour manager."

Kemmit remembers the event didn't go as well as had been hoped. "Paul was uncomfortable being away from home and was a handful on the trip. Jimmy Miller, the Stones' producer, helped in the recording. It was a spirited performance, but Paul wasn't fit, and Paul didn't have any material ready when Buzzy arrived for rehearsal. We got some songs from Andy Fraser of Free, and a few songs from Buzz and Paul. But Paul didn't take charge. We edited the entire performance down to perfection back in Woodstock, but when we listened to it Albert said he felt it was substandard Paul Butterfield."

Butterfield was also having health problems and his poor condition

may have had an impact on North-South. It was diagnosed

as peritonitis, an abdominal condition caused by a perforated

bowel that can be fatal and is extremely painful. The condition

required multiple surgeries in 1980 and 1981, and for a time Butterfield

wore a colostomy bag; his intestinal problems grew and he was

being treated by specialists. However, health conditions didn't

hamper his performances, when they occurred. "Paul loved

to perform, and he always gave everything when he performed, even

when he was not well," Kemmit recalls. "He would move

you. He was so good at what he did, and when someone gave him

an idea or a challenge he would rise to the occasion, attempting

to blow you away. He really wanted to impress you in performance."

you. He was so good at what he did, and when someone gave him

an idea or a challenge he would rise to the occasion, attempting

to blow you away. He really wanted to impress you in performance."

It might have been the peritonitis, the sudden, tragic death of Mike Bloomfield in early 1981 (due to a heroin overdose) or the realization of lost opportunities, but Butterfield entered the '80s with a new approach -- especially to performing. He was spending more time in California and did a series of shows with Gary Busey in the early '80s with members of the Band and Dr. John. "It was a big hit," Sally Grossman remembers. "A series of great shows they performed on the Strip. Everyone thought it would have been a wonderful thing if it had held together, but Busey was committed to movies and other things."

The shows were followed by the emergence of the Danko-Butterfield Band, Butter joining up with Rick Danko over the next couple of years. They performed regularly in the Northeast with a set list an assemblage of Butterfield and Danko/Band tunes performed in both acoustic and amplified settings. There was an appearance on Saturday Night Live and constant talk about albums. Their shows were frequent but often a mixed bag, depending on the mental state of the principals.

Butterfield was showing signs of serious drug problems and there is no doubt that years of drinking were beginning to take their toll on him physically. He had apparently warded off his doctor's warning to give up alcohol, and now his addiction to heroin -- an incredible turn of events given his rule in the '60s that heroin would not be tolerated among his band members -- was causing more problems. No one seems to know just when he started, but most point to the time after the surgeries, possibly as a self-medicated cure for the serious, lingering pain of peritonitis. Friends and family were aware of the lethal combination of the heroin or other drugs with peritonitis and they were becoming increasingly worried about him. Albert Grossman paid for many of his therapy sessions. The problem grew worse.

In 1982 Butterfield entered a Woodstock studio for a different kind of recording session, this time as a teacher on a set of instructional tapes. Although everyone identified him with the harmonica, no one had ever solicited Butterfield's expertise on playing the instrument, and with old friend Happy Traum on guitar Butterfield talked about learning how to "get inside" as a harmonica player, singing and playing by example. Harmonica players have often described the three cassette tapes as a Zen-like approach to instruction. But in fact, this is a tour-de-force presentation of Butterfield's acoustic playing and the finest evidence of his remarkable symbiosis with the instrument and the wellspring and depth of emotion he could spontaneously tap and communicate in his playing.

Years earlier, Stan Getz, another great melodic player of great emotional depth, had said, "Each person is an individual; each person is himself -- of the greats anyway; the rest are just copies in one way or another. There are a few people everybody gets most of their things from -- the greats. You hear other musicians all the way down the line not playing themselves because maybe they haven't found themselves yet. Maybe they're young. Or maybe it's an imitation of one of the true greats. And to mock, to imitate somebody else's music, makes the originator sound worse."

Butterfield would end the tapes suggesting that the listener tune in to Sonny Boy, Little Walter and Sonny Terry. For my money, these tapes provide some of the most emotionally nuanced acoustic playing you may ever hear. Through all his problems and time away from the stage, Butterfield had continued to work on his playing and had surely become much more than just a great amplified harp player.

Driftin' & Driftin'

When the news of Paul Butterfield's death was released to the public in early May of 1987 -- an overdose, resulting from a combination of drugs and alcohol -- it seemed like nothing more than the clichéd ending to another rock'n'roll story. But it wasn't.

It was perplexing to some. Others saw it as inevitable. But no one really expected it.

Many of Butter's oldest friends and bandmates had heard from him after his permanent relocation to Los Angeles, and as late as 1985 he had released Paul Butterfield Rides Again, not a good album, but one that showed him in good voice surrounded by friends like Blondie Chaplin and Paul Shaffer. His 1985 appearances had also been memorable, especially with old bandmates like David Sanborn and at the 20th anniversary of the Fillmore. Two tours, one in 1985 and the other in 1986, had been great musical successes. Chicago bassist/guitarist Danny Draher was on both and had played with harp greats James Cotton, Jerry Portnoy and Jr. Wells. He ranked Butterfield as a hero. "We were getting more back into the blues stuff. Paul was a good hearted cat, a stand-up guy, and I loved him. He was playing great, and singing real soulfully." Harvey Brooks remembers that "Paul always played his ass off. Regardless of what was going on offstage or at those gigs." In early 1987 B.B. King had included Butterfield in a special for HBO -- "B.B. King & Friends" -- and Paul's presence and performance was clearly a highlight of a show that also included Albert King, Stevie Ray Vaughan and Koko Taylor.

Butterfield was also in touch with a lot of old friends. He regularly called family members and was actively pursuing a growing relationship with his sons, Lee and Gabe. Old bandmates and L.A. residents like Trevor Lawrence, Ronnie Barron, Steve Madaio, Feiten and others heard from him, and they say he sounded great about his life and career. Rick Reed saw him just a few days before his death. "I was driving and saw him out running. He told me he wanted to get back into shape again and that he wanted to be near his kids. I really felt good about him."

Others saw another side -- a lonely, often uncomfortable and often paranoid guy prone to late-night, rambling phone calls, often under the influence of drugs or alcohol. Kemmit and many others spent time helping Paul get through the night. Finances became a problem; money was borrowed and never repaid from people who had been Paul's friends for years and those friendships ended. Others did out of frustration with the drug problems. Many bridges were burned.

Butterfield was shaken further when Muddy died in 1983, and then again when Grossman passed away in 1986. To many it was an erratic personal life at odds with the musician who could still perform brilliantly and work a crowd into a frenzy with his harmonica playing. The physical deterioration was blatantly evident to some. Sally Grossman recalls an early 1987 dinner she had with Butterfield and friends at Deanie's in Woodstock. "Paul looked terrible and seemed very weak. He kept falling asleep at the dinner table. After he left I called Rick Danko and told him that I thought Paul was very close to death."

"A lot of people worried about Paul," Bonnie Raitt remembers. "You know, the '80s were a very rough decade for a lot of us. Our kind of music was completely off the air; disco was in and then power pop and New Wave. We really felt disenfranchised on a lot of levels. For a lot of people what had been habits became serious vices. That everybody was suffering was obvious. A whole line-up of people showed it -- drug problems, heart attacks, health problems. And a lot of people fell by the wayside."

In the mid-'60s Eve Babitz was a Los Angeles teenager dialed into the burgeoning music scene there; she had grown up in a musical family and heard a lot of jazz and blues. When her friend David Crosby told her he wanted to take her to hear something she'd never heard before, she was ready. "You know, my dad is a musicologist, and when I first heard the Jefferson Airplane and the Grateful Dead and even the Byrds I just didn't think they could play. So when he took me to see the Butterfield Band at The Trip in L.A. I was just knocked dead. I thought they were just unbelievable musicians. And definitely not part of the '60s look -- they didn't wear the right clothes or have long hair or anything. So I just fell madly in love with Paul and decided I'd try to seduce him. I went to every show, and every night I'd change my look and get another person to introduce me to Paul. But the only thing that ever happened was I'd end up with Mike Bloomfield. I followed them from the Trip to the Whiskey and even to the It Club. It wasn't going anywhere and I just finally gave up.

"A few months later I ran into him again and he looked at me and said, 'Haven't I met you somewhere before?' Then later he saw me in New York and ran across the room to me and said, 'Eve, you look wonderful!' So I started following him all over again, but still with no luck.

"When I returned to L.A. I ran into Stephen Stills, and I got to do the cover for the first Buffalo Springfield album -- mainly because we were both such big fans of Paul Butterfield! We'd go to hear him and stay until four in the morning just to hear anything Paul would do.

Babitz, a writer now living in Los Angeles, continues: "Thirteen years ago I ran into him again here in L.A., and I'd heard how things hadn't gone well for him and he was a junkie, and I met him again. And he remembered me! I told him if he'd straighten up I'd go out with him, but he couldn't do it and he started going out with one of my friends. So I saw Paul a lot and knew what he was doing and heard all the stories.

"When Paul died it was so sad -- I knew he'd been hanging around all these people who loved and admired him -- but he just couldn't stay sober. I went to his funeral in Westwood, and it was a Buddhist service organized by his wife Kathryn. It was a huge gathering. The entire music business was there. All of the people that loved Paul, his family and all the women in his life. Everyone was so sad. Kathryn had all of us do some unison breathing, which was a Buddhist thing, and it was amazing how it calmed everyone down. Then she read a beautiful poem about a blackbird that landed in her window the day Paul died. They played some of Paul's music, and that cheered everyone up. And then all of the musicians that were there headed off to play music together."

This is an abridged version of the Paul Butterfield article.

For the complete article,

get the hard-copy version of BLUES ACCESS.

[Ed: We had to clip WAY more than we would have liked to make it fit here.

You owe it to yourself to read the full article (in fact, the whole series).]

The author would like to thank those that contributed to this, the final installment of my series on Paul Butterfield. Here's a brief bio on each.

Eve Babitz is a journalist and novelist living in Los Angeles. Her latest book, Black Swans (Knopf), is a collection of short stories.

Harvey Brooks lives in Connecticut. His band SloLeak released their first CD last year. He is a member of Jimmy Vivino and the Rekooperators, along with Al Kooper and Anton Fig. The band recently released its first CD.

Danny Draher lives in New York City. He is still active as a bassist and guitarist, recently recording with Jimmy Vivino, Bugsy Maugh, Mark Naftalin and Billy Davenport.

Sally Grossman lives in Bearsville, New York, and is still involved with the record label.

Levon Helm is the drummer/vocalist with the Band. Their most recent CD is High on the Hog on Pyramid/Rhino Records.

Ian Kemmit lives in Woodstock. He is currently working for RCA Records as an independent catalog album producer.

Bonnie Raitt lives in Los Angeles. Her most recent CD, a collection of live performances, was released late last year.

Rick Reed lives in Malibu. He is currently playing with John Marx and the Blues Patrol.

Dan Weiner lives in Monterey, California. He is an owner of Monterey

Peninsula Artists.

Special thanks also to those who helped with this story: Butch

Denner, Bill Bentley, Kathryn Butterfield, Peter, Pam & Jessie

Butterfield, Gabe Butterfield, Sam Lay, Billy Davenport, David

Sanborn, Bob Sheehorn, Buzz Feiten, Fritz Richmond, Geoff Muldaur,

Regina Wells, Tali Madden, Ward Gaines, Trevor Lawrence, Steve

Madaio, Pierre Beauregard, Mike Turk and Elizabeth Barraclough

for her consideration.

Previous installments of the Paul Butterfield Story appeared in BLUES ACCESS numbers 23, 25, 27 and 29. All except #27 are still available as back issues. Photocopies from #27 can be purchased for $2 from BLUES ACCESS.

|

|