Luther Allison & Johnny Copeland

In Memory

| Fallen Giants Remembered Luther Allison & Johnny Copeland In Memory |

|

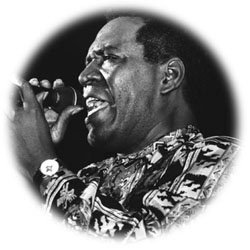

Johnny Copeland (1937-1997) |

|

Luther Allison (1939-1997) |

|

Johnny Copeland died July 3 in New York City following complications

from heart surgery. He was 60.

Copeland, a Grammy-award winner and multiple W.C. Handy Award winner, had undergone eight heart operations since 1995, including a heart transplant on New Year's Day. His final surgery was to repair a defective valve in the transplanted heart he had received. Prior to the transplant, Copeland lived 20 months with an LVAD (left ventricular assist device), a mechanical pump implanted in the abdomen, while the search for a suitable donor heart continued. No one has survived as long using the LVAD, which was approved by the Food and Drug Administration in 1991 for experimental use in patients who would otherwise die. Copeland, nicknamed the "Texas Twister," was a diverse, energetic performer who integrated his blues roots with African rhythms and jazz influences. Born March 27, 1937, in Haynesville, Louisiana, Copeland moved with his family to Houston in 1950. He joined the Dukes of Rhythm in 1954 but soon began performing under his own name. He signed with Don Robey, founder of the Duke/Peacock label, in 1957, but did not record for him. In 1958, Copeland's first recording, "Rock and Roll Lilly," on Mercury, became a regional hit. Copeland also had a hit with "Down on Bended Knees" in 1963. Copeland's career picked up steam after he relocated to New York in 1975. He began touring in 1979 and the release of Copeland Special on Rounder in 1981 brought him unprecedented success as well as a Handy award. Copeland, who considered T-Bone Walker his primary guitar influence, was by that time experimenting — quite successfully, on albums such as Bringin' It All Home in 1985 — in recording with African musicians. He also teamed with Albert Collins and Robert Cray in 1985 on the Alligator release Showdown, which won a Grammy for best traditional blues recording. He developed a strong following in Europe and was awarded the Big Bill Broonzy award from the French National Academy of Jazz and the Grand Prize for Recordings from the Montreux Jazz Festival. More recently, Copeland recorded for Verve, his last release being Jungle Swing in 1995, which returns to his African influences and also includes several acoustic tunes. Copeland continued to tour despite his health problems, and his condition drew mainstream media attention from ABC's Good Morning America, NBC's Nightly News, CBS's Newswatch, CNN and People magazine as well as blues- and guitar-specific publications. (See BLUES ACCESS #26 for more on his heart condition.) Copeland was by all accounts an inspiration during his illness and hospitalization, performing dozens of concerts for patients at Columbia Presbyterian Medical Center, where he was being treated. After his transplant, Copeland began touring again in April and performed dates through May. Copeland is survived by his wife, Sandra, of Teaneck, N.J., two sons and five daughters. Donations, condolences or cards should be sent to: Johnny Copeland Heart Fund, c/o Manny's Car Wash, 1558 Third Avenue, New York, NY 10128. — Bryan Powell (both obits) |

Guitarist/vocalist/bandleader Luther Allison died Tuesday, August 12, in

Madison, Wisconsin. He was 57.

Allison was diagnosed with inoperable lung cancer and metastatic brain tumors on July 10 after suffering dizziness and loss of coordination. Allison performed that night in Madison, just hours after being informed of his condition. He played his last concert in Minneapolis, Minnesota, the following night, then canceled remaining tour dates to begin outpatient radiation therapy. His condition worsened, and he was admitted to the University of Wisconsin hospital on July 30. Although suffering from blurred and rolling vision, Allison reportedly was not in pain as a result of his condition. Luther Allison had climbed to the top of his profession at the time of his death, picking up five 1996 W.C. Handy Awards and added three more for 1997, including Blues Entertainer of the Year both years. A famously intense, energetic performer, Allison was on tour to promote Reckless, his third Alligator Records release, which followed 1994's Soul Fixin' Man and 1995's Blue Streak. The albums were part of an extraordinary American comeback for Allison, who after career disappointments in the U.S. had moved to St. Cloud, France, near Paris, in 1984. Like many American expatriate artists before him, Allison's career flourished overseas; he recorded a number of albums that were released only in Europe. Until 1994, he returned to America seldom, playing gigs, visiting family in Chicago and his summer home in Madison. Allison was born August 17, 1939, in Widener, Arkansas. He moved to Chicago with his family in 1951 and dropped out of high school in 1957 to devote his energies to his band, the Four Jivers. He soon became a regular performer on Chicago's West Side club scene, drawing encouragement from Freddie King, among others, along the way. His first album, Love Me Mama, was released on the Delmark label in 1969 to substantial acclaim. In the early 1970s, he signed with Motown as the label's lone blues artist, releasing three albums that are not widely considered among his best work. While his U.S. recording career floundered, Allison was developing a following on the European festival circuit in the late 1970s, laying the groundwork for his relocation. Soul Fixin' Man was his first U.S. album in 20 years and marked his return to the American scene, enabling him to finally realize the success on his home turf that had eluded him years before. Funeral services were followed by a memorial jam session at Buddy Guy's Legends club. Allison is survived by his business and life partner, Carolyn "Rocky" Brown; Mrs. Fannie Mae Allison; sons Luther T. and Bernard, stepchildren Carolyn, Frank, Juliette, Rose, Joanne, Ray and Connie; three brothers, two sisters, 25 grandchildren and 30 great-grandchildren. Allison's medical expenses were not covered by his insurance, according to his management company, Blue Sky Artist Management. Alligator Records reports that contributions may be sent to The Blues Community Foundation, Box 607698, Chicago, IL 60660 (specify "Luther Allison Fund" on the check).

| |

The looks on the faces surrounding Holly Bullamore in the lobby of the Best Western in Davenport, Iowa, on July 4 pretty much told me all I needed to know. For nearly two years Johnny Copeland's friends had agonized while he waited for just the right heart to become available for a transplant, felt cautious joy when he finally received one on New Year's Day, then watched helplessly as he underwent repeated operations for "minor corrections." So I was already steeled for what Holly -- Johnny's manager -- had to say: "Heart surgery ... Johnny didn't make it." But it didn't necessarily cushion the blow. I first made Johnny's acquaintance in Memphis when I presented him with an award at the 1987 Handys. I thought his performance -- and his stage presence, with the guitar strap that proclaimed T E X A S -- was electrifying. I was initially drawn to his music by his African album, Bringing It All Back Home, and when I got the opportunity to interview him for BLUES ACCESS in 1991 we talked quite a bit about his experiences recording in Ivory Coast and the things he learned from the musicians he met in Africa. That night we caught his band at a club in Denver. We were going to leave after the first set, but he implored us to stick around. Good call: He closed the show with a lo-o-o-ong version of "Kasavubu" that had everyone whirling around the room. Several years later, I was in Baltimore, where my father was undergoing open-heart surgery. After a couple days on tenterhooks, there was nothing for the family to do but wait and see. I looked in the newspaper: Johnny was appearing that night at the 8 X 10, and I knew I had to go and blow off some of the tension. We spoke for a while before he went on and he was incredibly sympathetic about my dad's condition (empathetic, really, but I didn't know that at the time). He then proceeded to just about rip the walls out of the place; it sure did my spirit good. From then on, whenever I talked to him he never forgot to ask how my father was doing. My first real indication that all was not well with Johnny came at the King Biscuit Festival about a year afterwards. He walked to the side of the stage in mid-song, looking ashen. He ended up in the hospital that night, but returned two days later to play at the Handy Awards. Other nights and other shows he was vintage Johnny. At Billy Blue's in Denver, he was just pouring it on, resplendent in a red suit, and during "Life's Rainbow" I remember thinking, "Now this must be what Otis Redding did to a crowd." The vibe was that strong. The next time he came to town was in 1995 and I took the whole BLUES ACCESS staff to see him. They were wowed, but I felt like something was missing. Sure enough, a few days later he had a heart attack. The last time I saw Johnny Copeland, he was in Saint Anthony's Hospital in Denver. He was wearing an oxygen breather, but spent half the time talking to friends on the phone. (His wife, Sandra, said he'd been on the phone ever since they'd brought him to his private room.) He figured the main problem had been the altitude and he expected to be playing again when he got back home to New York. He did play again, but his doctors were not so cavalier. The wait was on for a new heart. Johnny and I were to have crossed paths twice this year, but it wasn't to be. His gig at the Denver Blues Festival was canceled at the last minute when he again had rejection problems; he didn't live to play the festival in Kansas City. Early in life Johnny Copeland was a boxer, and that fighting spirit and determination were evident throughout his life, even in the way he left it. His music was full of energy, too, but his songwriting -- something he never received nearly enough credit for -- resonated with a kind of sensitivity not often found in the blues. Like his friend, Luther Allison, he was one of the special ones. Today the tree they grew on -- if we could find it at all -- would be watered with a million tears. -- Cary Wolfson

|

Here is a sampling of online comments that followed the passing of Luther Allison. He did so much for blues in France that every blues fan around here felt like he KNEW him.

Vincent Vialard

Dave Daubard

Dee Grimsrud

Russell J. Bauman

No other muscian has ever touched me with their music, their attitude, their karma; everything about him exuded positive energy. God bless you, Luther. We will all miss you more than many of us yet realize.

Gloria Pierce

Luther Allison was a beautiful human being, in addition to a truly world-class bluesman. I was shocked and saddened by his sudden passing, and that I never had the chance to say to him, "Luther Allison, here's what I've done!" Edward Liu

Michael Cloeren

|

|

|