The Holmes Brothers' Awakening

by Tim Schuller

| Road Warriors The Holmes Brothers' Awakening by Tim Schuller |

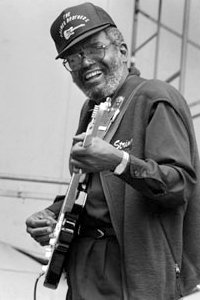

The turnout was surprisingly scant but made up of those in the know, who'd heard the trio's critically acclaimed CDs (they've done four for Rounder and one for Real World) or caught wind of their dizzying, diverse live performances. Comprising Wendell and Sherman Holmes on guitar and bass, respectively, and Popsy Dixon on drums, the threesome played to the small but enthusiastic audience as though it were a packed house, a testimony to their professionalism.

Typically (for them) they drew from a headspinningly varied music palette, from low-down blues to gospel, yee-haw C&W to pop. Popsy's gilt falsetto, Sherman's baritone and Wendell's gutsy shout comprise a tripartite vocal front bolstered by their knack for sounding soulful and persuasive at anything they sing. From them, the Paul McCartney meringue "And I Love Her" acquires new depth and Tom Waits' "Train Song" (sung chillingly by Popsy) becomes an epiphany. From the deep-dish blues of Jimmy Reed to their own R&B churners "Final Round" and "Easy Access," they range with ease, each show ratifying the rave reviews in their burgeoning press kit.

In 1992 the HBs did a gospel CD, Jubilation, for Peter Gabriel's Real World label, and they have appeared on WOMAD (World of Music and Dance) tours that Gabriel fronts. They've even been in a movie, John Rubino's Lottoland. Arguably, they were the movie: Sherman and Popsy had cameos as themselves; Wendell had a starring role as musician/building superintendent Milton; and their music makes up the soundtrack. Though recognition has arrived, they're not exactly newcomers.

Sherman and Wendell were born in the Tidewater region of Virginia,

their surroundings rural but rich in culture. They took music

lessons, sang gospel in church and headed up a combo. They had

weaned on down home blues at a cousin's nearby country

juke joint, so naturally they played blues but, less characteristically,

played C&W as well.

Sherman and Wendell were born in the Tidewater region of Virginia,

their surroundings rural but rich in culture. They took music

lessons, sang gospel in church and headed up a combo. They had

weaned on down home blues at a cousin's nearby country

juke joint, so naturally they played blues but, less characteristically,

played C&W as well.

"White (radio) stations had more kilowatts than the black stations," laughs Wendell Holmes during an interview later. "We'd be listenin' to the blues, and all of a sudden, poom, you'd get Hank Williams. That was good for us. We loved doin' country & western. Lots of people find it strange that black folks'd do country & western, but we do lots of it -- and like it."

Sherman was the first of the brothers to move up North. "He went to Virginia State University a couple years and in 1959, went to New York because he had a gig with Jimmy Jones of 'Handy Man' fame -- he did [the song] before James Taylor or Del Shannon or any of those people, the original Handy Man," Wendell explains. "So Sherman was workin' with him, and when I got out of high school, he picked me up on my graduation night and took me straight to New York. So I got a gig playin' with Jimmy, and I thought I was a big star. But he wasn't payin' much money, so that didn't last long."

"After we came out of Jimmy Jones, Sherman and I formed a group called the Sevilles. That was in '62, I would say. We used to play in Great Neck at a club called Gibson's. All the R&B stars came through there, Thursday, Friday and Saturday. We were the house band there for over a year so we got a chance to work with so many people, like Shep & the Limelites, John Lee Hooker, Jerry Butler, the Impressions -- it was great experience."

Wendell also did dates with "Wild" Jimmy Spruill, who'd played guitar on the hits "Kansas City" by Wilbert Harrison, "The Happy Organ" by Dave "Baby" Cortez and other notable records and played such historic Apple nighteries as Small's Paradise, the Baby Grand Club and the Central Ballroom.

"I knew Jimmy very well," says Wendell. "He was a good friend of mine, and we used to do gigs together. Wild Jimmy Spruill. He was a great showman, played guitar with his teeth. He had a special sound, used Standel amps, which they don't even make anymore, and he'd customize 'em. He liked to work on guitars and amps and built amps toward the end of his life. He just died, had a heart attack on a bus or somethin'." (Spruill died February 3, 1996, in the Carolinas, on the way from Florida back to his home in the Bronx.)

Post-Spruill, Wendell hired on as guitarist for Inez and Charlie

Foxx, who'd had a hit with "Mockingbird,"

and during his three-year stint with them toured the U.K. and

Canada. He teamed with Popsy Dixon in a trio led by singer/keyboardist

Tommy Knight for a decade, playing blues, black Top-40 and organ

jazz in New York, New Jersey and Connecticut. Dixon, also Virginia-born,

has an even more extensive gospel background than the brothers.

The trio disbanded when Knight moved to Florida, but Popsy and

Wendell found that Sherman had a berth for them at an East Village

bar that had started staging blues.

Post-Spruill, Wendell hired on as guitarist for Inez and Charlie

Foxx, who'd had a hit with "Mockingbird,"

and during his three-year stint with them toured the U.K. and

Canada. He teamed with Popsy Dixon in a trio led by singer/keyboardist

Tommy Knight for a decade, playing blues, black Top-40 and organ

jazz in New York, New Jersey and Connecticut. Dixon, also Virginia-born,

has an even more extensive gospel background than the brothers.

The trio disbanded when Knight moved to Florida, but Popsy and

Wendell found that Sherman had a berth for them at an East Village

bar that had started staging blues.

"Sherman was workin' with Bill Dicey, a harmonica player," remembers Wendell. "This place opened -- Dan Lynch's -- on 2nd and 14th, and they started playin' there. About a month after they opened, I came in and brought Popsy with me, and we started at Dan Lynch's back in '79. The Holmes Brothers as it is today came out of Dan Lynch's."

This storied saloon was no better than it needed to be (for proof see Adam Gussow's columns about it in BLUES ACCESS #28 and 29). With weekly jam nights, generous drink specials and performances by Little Mike and the Tornadoes, Satan and Adam, Robert Ross, Popa Chubby, Mark the Harper and, of course, the brothers, it served as a meeting ground for many members of New York's blues community.

Among those the Holmes encountered there was Len Kunstadt, who'd married "classic" blues singer Victoria Spivey and was her partner in the Spivey record label. Spivey LPs, with their crude cut-and-paste covers and lower-than-lo-fi sound quality seem quaint today, though in fact they seemed quaint when they were brand new. When Victoria was still around, her cronyism could get notables like Homesick James, Memphis Slim, Roosevelt Sykes, St. Louis Jimmy and even a very young Bob Dylan to cut for the label. After her passing, the label released a few more dispirited albums, including one by the Holmes and Dicey, but Wendell disowns it.

"I hate that record," he says. "I'm surprised you know about it. We recorded it on a li'l ol' four-track machine right in Dan Lynch's, and the sound was terrible! I played it once and never played it again."

Dan Lynch's was also where the Holmes Brothers were heard by producer Andy Breslaw, who juiced their signing with Rounder. In 1990 their debut In the Spirit came out, followed by Where It's At in '91. The following year, Peter Gabriel entered the loop.

"We were doing a Benson & Hedges Blues Festival,"

recollects Wendell. "Peter Gabriel had -- I guess

you'd call 'em scouts there, and they hooked us

up with him. He invited us to a 'recording week' at

his Real World studio in Bath, England. There were musicians from

all over the world there -- Africa, the Laplands --

and the Holmes Brothers were there as 'R&B guys from

the states.' We cut a compilation album (A Week in the

Real World) with some other people, and then everybody had

the chance to record the album of their choice, so we did Jubilation.

Peter was always there during production, and you wouldn't

believe, he's just a down-to-earth, regular person. But

man, that studio's fabulous! They say it cost 20 million

bucks, and I can believe it."

"We were doing a Benson & Hedges Blues Festival,"

recollects Wendell. "Peter Gabriel had -- I guess

you'd call 'em scouts there, and they hooked us

up with him. He invited us to a 'recording week' at

his Real World studio in Bath, England. There were musicians from

all over the world there -- Africa, the Laplands --

and the Holmes Brothers were there as 'R&B guys from

the states.' We cut a compilation album (A Week in the

Real World) with some other people, and then everybody had

the chance to record the album of their choice, so we did Jubilation.

Peter was always there during production, and you wouldn't

believe, he's just a down-to-earth, regular person. But

man, that studio's fabulous! They say it cost 20 million

bucks, and I can believe it."

It was again through the connections of Breslaw that the three got involved with Lottoland, a shaky little movie shot on the fringe of Brooklyn's Park Slope in which four people (including Wendell's character Milton) find love despite the hardness of their 'hood, all to the tune of citified soul from the Holmes. It's a wistful, chatty flick, and it's not completely fanciful to compare Wendell's role to jazzman Dexter Gordon's in Round Midnight. Both played themselves in a large sense, but brought credible, intuitive acting to the table.

With the release of the Lottoland soundtrack, the Holmes Brothers had made five CDs in not quite five years. Such prolificacy would've depleted many bands, but Promised Land is their strongest display to date. Wendell wrote five songs, Sherman two. Virtually all the instrumental work is by the core trio, and their musicianship is deliciously sparse, their self-containment all the more remarkable for the broadness of their range. Their diversity has been more to their advantage than a straight blues repertoire would be.

"Up until recently, blues wasn't a big thing in New York," says Wendell. "It's only in the last few years that there's been a blues scene, with clubs like Manny's Car Wash and Terra Blues. All those places make it a much better place than it was for guys like me and my brother's generation. Although we worked all the time, [it was] because we could do black Top-40, country & western, gospel and whatever it took to do a lot of club dates. We had day jobs from time to time, but I supported myself mostly on my music, and so did Sherman -- it was always, always the highest priority."

With a knowing grin that might've come from Lottoland's Milton, Wendell adds, "That's one thing that's not likely to change."

|

|