about growing up in the South, race, accomplishments, regrets, the crawdad and the crawdad hole and how he developed the best live show in the blues.

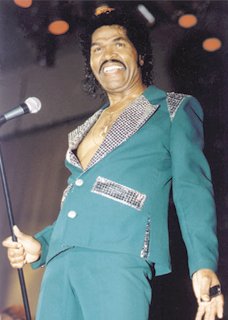

BOBBYRUSH! What it should be, really, a soft drink, soft but hard, loaded with caffeine. Bobbyrush! A brand name.

Though his recording career didn't take off until he recorded his first hit, "Chicken Heads," for Galaxy in 1971, Bobby Rush has made more than 160 records, many of them regional successes, and could do many shows without repeating a single number. His songs reveal the man's boldness and command of his idiom, from primitive harp to sophisticated synthesizer. He is, like Bob Dylan, an inspired synthesist. A partial list of his influences would include Percy Mayfield, Sonny Boy Williamson, Solomon Burke, Don Covay, the Beatles, Willie Dixon, Leiber & Stoller, Otis Redding, Robert Johnson, Phil Harris, the Doors, Sammy Davis Jr. and Arthur Godfrey. The first Bobby Rush record I remember hearing was "Wearin' It Out," recorded in 1983. It was my introduction to the persona of his "Bobby Rush" character, a sort of cross between Dr. Ruth and Jelly Roll Morton's "Winin' Boy." The theme that persists, from Wearin' It Out through Sue, What's Good for the Goose Is Good for the Gander, Handy Man, One Monkey Don't Stop No Show, Hen Pecked and Lovin' a Big Fat Woman is unselfish love and devotion, which Bobby Rush somehow manages to make deliciously scandalous and exciting. In the following account, I try to avoid invidious comparisons between Bobby Rush -- it's a stage name, and he likes it used in full -- and great historical figures like B.B. King and John Lee Hooker, who have not made an exciting recording in years. Bobby Rush, in his mid-60s, continues to make first-rate R&B records and to have the best stage show since Ike and Tina broke up. If my friend Mick Jagger were hip enough and wanted to revive his career -- instead of endlessly dragging his scrawny ass around the planet regurgitating his greatest hits -- he would cut Bobby Rush's "Jezebel." But he's not hip enough, nowhere near as hip as this senior citizen from Houma, Louisiana, southwest of New Orleans, within spitting distance of the Gulf of Mexico. Not Houma proper but a farm near there. Bobby Rush is the real thing, as country as a tree full of owls or a passel of possums. But he's also at least as up-to-date as Kansas City. After admiring him from a distance for a decade and a half, I finally caught up with him at the eighth annual Springing the Blues Festival at Jacksonville Beach, Florida. He had not played there before -- in spite of his long career he has only recently emerged from the chitlin' circuit to start working municipal bluesfests and other venues where the audience is predominately white. Having lived for years on the South Georgia coast, I've observed that Jacksonville audiences set a standard for lifelessness, so I thought this would be a good test of Bobby Rush's much-anticipated (by me) showmanship. I met Bobby Rush at about one o'clock on a Saturday afternoon in early April. When I arrived at the Ramada Resort, where he was staying, he was in his room talking to a shapely blond in jeans. It was business, but I noticed what I considered a telling detail: the Gideon Bible was open on the table. A glass wall looked out on the beach and the long sweep of gray Atlantic. Bobby Rush, appearing at least 20 years younger than his age, had on black tassel loafers, black socks, black jeans and a black jacket trimmed with fake snakeskin. I was wearing a light tan Kuppenheimer sport coat I found at the Goodwill, resoled loafers trimmed with python and a great many scars. Between us Bobby Rush and I had well more than 100 years of blues experience. Since this meeting, we have spent many hours in conversation. A small part of our testimony follows.

"Until a few years ago," Bobby Rush told me, "nobody knew I exist. Not really. I'm probably the only one livin' who have did as well as I've done, and nobody know nothin' about me." He has a valid point. For one thing, there's a conspiracy against people with a sense of humor. But we'll get to all that. Earlier, I had asked about his life as a child. "My daddy was a preacher," he said. "He had a church in Houma and a church in Pine Bluff, Arkansas. He would preach at one church on the first Sunday and the other one on the third. As a kid, I was very involved in church, and going to church, but I never sung in the choir. I remember my first guitar, I made it out of a broom wire. I had a brick on one end and a bottle on the other end -- it was like what they used to call a diddley bow. I'd go to church on a Sunday, and the choir would be singing, and I'd be singing, but not in the choir. The ladies would be shouting and everything. We'd get out of church about one o'clock and come home, and my dad would have to go back and preach most of the time in the afternoon. I wouldn't go back to church with him. I'd play the guitar outside my house. And the same people that had been shoutin' in church, man, they'd be boogie-woogiein' with me, havin' a ball. I was about 10 or 11 years old."

Had you seen somebody who inspired you to be a performer?

"I had an uncle, O.B., and he would go to shows and dances and come back and I would say, 'Uncle O.B. Tell me what you saw last night.' He'd say, 'Why you wanta know?' I'd say, 'Tell me how you walked in the place -- what the star looked like -- what he had on.' Now what I'm doin', is dreamin'. You follow me? I would make him tell me, finally -- when he walked in the door what happened? When the star came to the stage, what happened? What the first song? What way he walked? How many steps he walked from the dressing room? I wanted to know everything he did so I could visualize like I was there and put myself in his shoes. I would just sit there and dream and grow up, and I could see myself as a grown man. I was 10 or 11 years old. I would go in and get some matches, scratch about four of five matches, put 'em out quickly so the end of 'em would get black, and I would use that matchstem to paint my little mustache on. Then I could visualize. I had my little guitar, and I would stand in front of the mirror in the chifforobe. I was seekin' out, then, what it took to make me stand out."

When you were a kid, you listened to WLAC? The broadcasting

service of the Life and Casualty insurance company, located in

Nashville, featured white announcers like Gene Nobles, "Hoss"

Allen and John R (for Richbourg), who played black music and became

regional celebrities. On clear nights WLAC reached as far south

as Jamaica. "I listened to WLAC, then I listened to all the country and western stations who were in my neighborhood, just local radio stations, and I listened to Roy Acuff and all that stuff, the Grand Ole Opry. My favorite song was a country-western song that went, 'You get the hook and I'll get the pole, baby -- you get the hook and I'll get the pole, we'll go down to the craw-dad hole.' I was the kind of child who, when I heard a song, if I liked the song, I put myself in the song. I could see myself with a fishin' pole -- which I learnt later, he wasn't talkin' 'bout a fishin' pole -- but to me as a child, I know about fishin', I know about the pole, I know about the crawdad hole, and the crawfish and mud and what have you. I related to it in that way. I found out when I got grown, he wasn't talkin' about fishin' at all. But as a child, you relate to what you know about. "I was like that even when I went to church. I would get carried away -- instead of me listenin' to the message, I would grab the message and put myself in the preacher's position, and I'd be goin' through the sermon like I'm preachin'. I'd be sittin' there rockin', and I'd be doin' what he's doin', but I'd be takin' it my direction. I used to go to movies, and I would be this person on the screen. I would be the preacher, I would be anything that struck my attention that I liked. And I would venture from him, and put myself in it, and I would do my own thing. That's kind of like what I did with music. I liked Howlin' Wolf's performances, and I liked Muddy Waters -- I liked most people that I had a chance to hear, but I wasn't exposed to too many blues guys at that time. Comin' from my house, my father a preacher, you didn't listen to that much radio playin' the blues. You'd listen to gospel stuff. So I didn't have a chance, until his back was turned, to listen to those kind of things."

Who were the first people you saw live? "Joe Turner -- Big Joe Turner. I saw him at a place called Townsend Park in Pine Bluff, Arkansas. I think the next guy I saw was Jimmy Reed. And Little Walter. And then come Howlin' Wolf and Muddy Waters." When Little Walter was in his band, Muddy Waters, verifying the authenticity of his sidemen, told an interviewer, "Little Walter got a bullet in he leg right now." Howlin' Wolf, who would have been the all-time winner, had there been such a competition, of the King Kong Lookalike Contest, would in those days crawl onstage on all-fours, holding in one hand a hammer, in the other a hacksaw. Samuel Beckett and Harold Pinter, their dramaturgic coevals, had nothing on these Thespians. In 1953, at 19, the stage-struck Emmit Ellis Jr. moved to Chicago, becoming, not long thereafter, Bobby Rush. "I gave myself the name Bobby Rush out of respect for my dad, because he's a preacher, and I'm a junior."

How did you select the name Bobby Rush?

It's a great blues name, Bobby Rush. "I think it is."

You've made it a great name. "I think it's got a little swing to it. You know, some presidents don't have -- their names don't ring. You know what I'm talkin' about? I think President Eisenhower -- that sound like a president. President Truman -- man, that sound like you in control. Truman, like a true man. Hellofa name. President Clinton, it sounds weakish. It don't sound like a authority name. I guess names don't have anything to do with a person himself, but I was lookin' for that ring. To me, as a kid, T-Bone Walker was so powerful. T-Bone Walker. That sound like a blues player. Muddy Waters. Muddy Waters sound like you in the alley, man. Howlin' Wolf -- come on, you can't beat this name. The Wolf. And what he do? Howl. Now, you know that's a name, man. I picked my name 'cause I have always been kind of a fast walker, fast talker, and had energy -- Rush fits me because it's energyfied. Bobby Rush -- you take a drink and it rush to your head. Speedy. "When I started doin' what I was doin' as a young man, I wasn't doin' it to arrive at anything. I was doin' what I loved and what I felt in my heart. I guess it's kind of like makin' money at what I do, 'cause when I first started to doin' what I do, I wasn't doin' it to make money. I never thought about this could get me rich or get me famous. That wasn't in my mind. It was somethin' I wanted to do. It wasn't about the money. Then all of a sudden, a few years later, somebody said, 'Well, Bobby Rush, you can make money doin' this.' I said, 'You mean I could make money doin' what I love to do?' That was the second incentive. The first incentive was: I just wanted to do what I do because I like what I'm doin'. It wasn't about the money, it wasn't about arrivin' at anything. Later that came in play. But at the beginning, for the first, probably 10, 15 years, I just wanted to be famous 'cause I could do what I wanted to do bein' famous. Not bein' rich and havin' all these things that come with riches. I never thought about it in those terms. What I thought about was that if I could be famous, then I wouldn't have to work as hard as some of the guys work at the steel mill or some other job, and yet I could do what I wanted to do. I'm a pretty good carpenter, and there are some other things I can do very well as a handyman and make a good livin', but that's not what I wanted to do. Music is what I wanted to do."

I don't claim to be no gardener

-- "Handy Man"

In 1992 Handy Man would become the title of a Bobby

Rush CD. But for years the young Bobby Rush pursued public appearances

in Chicago clubs to the exclusion of recording or more extensive

touring. Even for a professional entertainer he had, to understate

the case, remarkable stage presence, or presences. "Maybe '59, or it could have been '60, myself, Earl Hooker, Tina Turner, Ike Turner, used to work at a place called Bagerbar in Rock Island, Illinois. Earl Hooker told me about this guy, so [the club owner] and I got to be good friends. I started to playin'. I would go down and play every weekend, so the man said, 'Bobby, why don't you be my house band, come down and work for me Friday, Saturday and Sunday, or any night you can do it?' So I said, 'OK.' Then he says, 'Your show is so good, you're drawin' so many people, we need a MC or a comedian.' I said, 'I got just the man for you.' He said, 'When can you get in touch with him?' I said, 'When I get back from the weekend.' "This is on a Friday night. A gentleman in Chicago called Prettybop was a good comedian and a MC. Monday I went to him and said, 'I want you to go to Rock Island, Illinois, with me.' He's no longer living, he's dead and gone. He said, 'OK, I will.' I said, 'What kind of money will you do it for me?' He said, 'Well, I'll go down there for 25 or 30 dollars, long as you pay my room.' I called the man up, said, 'Listen' -- and I lied to the man, I said, 'The man want 50 dollars and you pay for the room.' He said, 'Tell him I'll give him 45 dollars and pay for a room.' I said, 'OK, you have a deal.' I went back and told Prettybop. He said, 'OK, I'll go.' It's like maybe Tuesday now. Come Thursday night, he calls me up and says, 'Bobby, I'm sorry, man, I just can't go, my wife ...' I don't know whether she was pregnant or what have you, but anyway, his wife didn't want him to go. Here it is Thursday night, and we're leavin' Friday mornin' early. I said, 'Well, think about it in the mornin'.' He said, 'Well, let me call you in the mornin'.' Next mornin' came, his mind still wasn't made up that he wanted to go. First he called me early that mornin'. He said, 'I think I can go, call me back at 11 o'clock.' Well, 11 o'clock was a little tight for me. I called him back at 11 o'clock, and sho nuff, he can't go. "I don't know what to do now, 'cause I was gettin' about 35 or 40 dollars a night, payin' my band like 20 dollars a night, as a bandleader. Now 45 dollars -- I'd pay him 30 dollars, and I'm makin' 15 dollars a night on this man. 'Cause he don't know what I'm getting. 'Cause I'm the agent, or whatever. I said, 'I don't know what to do.' Then I said, 'I got it!' My wife said, 'What's wrong?' I said, 'I got it!' She said, 'Tell me what you talkin' 'bout.' I said, 'I can't talk about it now, but I got it.' I had been doin' jokes and things on the bandstand, so I went to this Goodwill store and bought some overalls, I must have paid 20 or 30 cents for the overalls -- it was less than two dollars for everything. I got me a big hat, a big shirt and a big suit that you had to put a belt around, double it around you. Big suit. I dressed cleanly under this suit. I put this suit on top of it -- so I named myself the Tramp. The Tramp. That's all I said, the Tramp. "I went to the club that night. I said, 'Ladies and gentlemen, we got a MC with us tonight, a comedian, he's MC-ing the show, his name is Tramp. I'm goin' back there and we gone start the show.' I go back in the room. I said, 'Ladies and gentlemen, let's give a hand to the Tramp.' I walk out on the flo', I tell some jokes, stay on the stage 15, 20 minutes, doin' my routine like a stand-up comedian and just killed the people. I'm a born comedian -- you can hear it in my songs. In the early days, I used to stop the band in the middle of the night and do a couple of stand-up jokes. Anyway, this particular night, I called my own self on and just killed the people, things just went right. I said, 'Now, ladies and gentlemen, it's star time. You're here to see Bobby Rush, and here's Bobby Rush. Ladies and gentlemen, let's welcome -- Bobbeeeeee -- Rush! ' I stepped back behind the curtain, stripped them big pants off, already dressed underneath. I didn't wear a mustache then -- I snatched my mustache off, I had it stuck on my face -- stuck it down in my pocket and walked out on the stage. I did that for almost five months before the man found out."

He didn't know it was you? "He did not know -- the man was payin' me, I think I was gettin' 90 or 95 dollars a night. That was money in them days. 'Cause I'm gettin' my money and the MC's, and he don't know that it's the same person. When he found out five months later, he came to me, he said, 'Man, let me tell you somethin'.' And I guess that's the first time a man just sat up and called me the name motherfucker right up in my face. He said, 'You a lyin' motherfucker.' He said, 'But you damn good. Don't let no motherfucker know it but me.' And he kept me there for a year! That's where the change of clothes come in -- it was did because I cheated the man, and it started workin'. I'd come out as the Tramp; then I'd come out as Bobby Rush. And the public did not never know. Really, what I was, a MC."

Really what you were was a great actor. "Yeah, that's 'bout what it is. And even when I'm on the bandstand, my moves and what I do on the bandstand, it's acting. I'm a actor."

Dangerous -- let me tell y'all what dangerous

really is

-- "Dangerous"

"Someone asked me what's my biggest downfall. I guess my biggest downfall, that I didn't take advantage of the people who loved me, who really loved me for me. That was Albert King, Muddy Waters, Howlin' Wolf and Little Walter. Let me tell you what these guys used to do, when I was just a teenager. They used to call me and say, 'Hey, Blood, come go with me.' I don't know what kind of person I was for a grown man to want a teenager to follow him. "I look back on that and I tell you that my daddy, when I was 10 years -- now, 'bout what I'm 'bout to say now -- a pair of mules and a wagon was a very important thing to a farmer. But he would trust me with a pair of mules and a wagon at 10 years old. And at 10 or 11 years old, I would take it to town to gin the cotton and bring it back. Now, that's 10 or 15 miles. That's a lot of trust in a kid. I must have been a trustworthy kid. He'd say, 'You take this to town, and here's what you do. You go and ask Mr. Bill what the cotton sellin' for today. If it's high enough, you sell it, if not, decline to sell it, bring it back, we sell it later.' He let me judge the price. And I know the going price -- if I'm gettin' 15 to 18 dollars, out of -- when you gin the seeds, you sell the seeds, you know? But I know if they anytime below 12 dollars, we'll wait till the next week. They might go up. They go up and down, rise and fall. Next week, when they go up, we sell. You sell when the price is up. But my daddy let me judge. "I remember one time I come back home, and I sold for $12.90. My mother said, 'You could have waited.' My daddy said, 'That was his judgment.' I sold because I heard some white guys talkin' about, 'Next week the cotton goin' down.' I'm a little boy. I'm hearin' these grown mens as they politically talkin', and white mens at that, talkin' about the price goin' down. And I sold. And next week, sure enough, went down to like eight dollars. My dad knew that, if I made the decision to sell, there's somethin' behind it. Even if it was wrong, I made a good decision for the time. I didn't think about it until it was too late to ask my dad why he did this, but I must have been a pretty trustworthy kid."

In the 1980s Bobby Rush bought a house in Jackson, Mississippi.

It made touring deep-South clubs easier, but it required violating

a prohibition Bobby Rush had known all his life. "At a young age, my mother, you couldn't tell whether she was white or black. One day we went to town, a little place called Carquit, Louisiana, about five or six miles from where we lived near Houma. Carquit also is my publishing company name and my son's name. We didn't have a car at the time -- we had to drive a wagon. I came to town with my mother and father. At that time all the kids couldn't come to town to buy shoes, so what my mother and dad would do is take a string and medjur the kids' feet with a string. And you put a piece of tape on it and you write their name on it. And you buy shoes accordin' to the length of the string. So I went to town, and I didn't get out the wagon. My daddy got out the wagon, went in the store. He was in the store for 10 minutes, maybe, and these two or three white guys come up. They knew my mother. Her name was Mattie. They said, 'Hey, that Mattie?' My mother looked around. She said, 'Yeah.' One of them said, 'She with that nigger.' He said, 'Where that nigger that you with?' So my mother looked around, she said, 'He's in the store.' They said, 'Well, what you doin' with this nigger?' She said, 'I'm a nigger, too.' She got out of the wagon, walked back to the back of the wagon, and they went in the store. I couldn't hear every word she said, but my mother bein' a good lookin' woman, and a smart woman, I know now that she fronted for my daddy. She went and told these white guys who she was and what she was doin'. She had to prove to them that she was black also."

How did they know her name? "Looking back, this guy who was with them who was the third person, knew her name. And I guess he must have told them, 'Mattie got this black man.' "

But he didn't know she was black? "He did not know. He went inside, but he believed this guy in the store. Apparently the store owner assured them that she was also what they call a nigger. Then she came out of the store, and she talked to these guys, and they talked with a smile. So whatever my mother told these gentlemen was soothing. 'Cause my mother was smart enough to cover up for my daddy. Because they was comin' there to do harm or start somethin'. But my mother took care of it. And I know my mother covered it up, because when my dad came out the store, he didn't know what went on. And my mother never mentioned to my daddy 'bout nothin'. "I saw it happen again a year or so later. Two white guys came to bring ice. At that time they had ice men comin' by your house. We lil' kids sittin' out in the yard, and the ice men come, and most of the time they would come to the gate, open the gate and come in. So I'm sittin' by the gate playin', and someone said, 'Hey -- it's some niggers in here.' Referrin' to us, my sisters and brothers, the kids. He said, 'I thought some white folks live here. We been bringin' this ice to niggers all this time?' 'Bout this time he says, 'Hey! You want some goddamn ice?' My mother walked to the door, he said, 'Oh, I'm sorry, ma'am, I thought niggers were livin' here.' "My mother said, 'We don't use that kind of ice. But we use ice.' That's what she said to 'em. And they went on to serve her not knowin' whether she was black or white. But they thought she was white, because when she walked out, they said, 'We thought niggers lived here.' We was kids playin' in the yard, just lil' bitty kids, couple of sisters and brothers of mine, the rest of them was in the field workin'. Anyway, they continued to bring ice, I don't what ever come of that, I don't know what she said to my father about it, I was too young to know what happened, but I remember that situation. I wasn't frightened about it, 'Cause I'm a kid. He told her, 'I thought niggers lived here.' When she come to the door, because she looked like this blond-haired white woman. She had blue eyes and blond hair."

But this came about because of -- I can't remember

whether it was your great-grandmother or grandmother. "What happened was -- my great-grandmother and grandfather was from Jackson, Mississippi. We was told as kids not to never come to Jackson, Mississippi. Now, my mother explained to us why. She said, 'Because my grandmother -- which is yo' great-grandmother -- and grandfather was a slave. Yo' great-grandmother was a slave, and she was the youngest one could walk out of 10 children.' There was a couple under her that was too small to walk. But the ones who could walk, they were five, six, seven, on up, up, up, these kids, their half-brother, which was a white guy, who was half-brother to my great-grandmother, taken them from Jackson, Mississippi, and fleed with them to Eudora, Arkansas. He stole his sisters and brothers from his daddy."

And he set them up in living quarters in Eudora? "Way my mother tell it, he left them with someone he knew there who had a house. They had used to work some kind of way with his daddy. They was black, workin' for this white man. He set 'em up so they could farm and be free. Because they had the same daddy and different mamas."

This is before the Civil War -- when? 1850s? "My grandmother, if she were living today she'd be 108. We talkin' about her mother's mother. My mother was born 1906. And my grandmother -- had to be 1885, or somethin' like that, probably. Fifteen-20 years old when she had my mama. You can step it back like that. She had 'em very young. She had all the children -- 10 of 'em -- before she was 30. So you may be talkin' about 150 years back, or 175 years back."

You were telling me that the man had so many children with

his wife, and so many ... "He had a lot of children. He had at least five or six children by his wife. He had five or six children, maybe seven -- it could of been eight by this black woman which was my great-grandmother. But there was two children that they never saw anymore. But they stayed back with they mother, which was his concubine, which was my great-grandmother. My great-granddaddy, I don't know what happened to him. I understood that he worked for this white man and dared to open his mouth about all these children that were none of his. Although they had a couple of children, but I don't know that side of the family. I just know this white man's children who had a chance to flee from this man. There was a couple more, maybe three more, that they never saw any more. He willed land to my great-grandmama and the children. I understand it was a great confusion when he died. I don't know what the confusion was, but I know we was dared to come back this way again. And I think out of my family I'm the first one that migrated back. I was told, definitely, to never come back this way. I was told that from the time I was born. My mother always taught, 'Don't ever go to Mississippi. Don't ever go to Jackson.' "

I guess at first you didn't know what she was talking

about. "As a young boy I didn't know, but after I grew up, I knew what she was talkin' about. I knew before I decided I was gonna move there. It's a touchy thing. I haven't talked about this, not in a single interview. I never talked about this, noplace. I never mentioned this to nobody but my family. I didn't mention it while my dad lived."

You made a decision to go to Jackson. From your childhood,

you heard, "Don't go there." Like telling

a Jew not to go back to Germany or Poland. But you made the choice

to do that. "I wanted to make a difference. Because when you run away from a situation, that don't solve the problem. Why don't you go back and straighten out the mess? Because, see, if I have the ability to straighten it out, then it's my responsibility. Because if you don't have the responsibility to do it, then it ain't your responsibility to even try. See, woe unto the man who knows better and don't do better. He will be whipped with many stripes. I think I'm a perfect example of one who can cross this bridge, come back. Because I'm gonna tell you something, I have no beef with my people, if I ever find them or whoever they are. It ain't no beef with them about what it is. It's about the whole situation. Whether they black or white. Somethin' need to be done -- the truth need to be told. What happened so long, I think we as a race have shut our mouths too long. We get shocked about the black and white issues, the things we know, that we don't wanta tell no one, so what we learned we don't wanta pass it down, and we get caught up in this kind of situation."

subscribe to the hard-copy version of BLUES ACCESS.

|

"No, I hadn't. I've been a dreamer all of

my life. I remember at six or seven, eight years old, workin'

in the cotton field. One time my mother hit me in the head with

a cup, because I was standin' in the field at 11 o'clock

or almost 12 o'clock in the daytime, lookin' up

at the sun, and the sun was just cookin' me. And I did

not see the sun, or feel the sun. I wasn't aware that I

was lookin'. My mind was gone into a deep thought, and

I could see myself onstage. Doin' what I do now. I could

visualize -- when I was 10 -- me bein' 20.

I'm a big man, I done grew up, and I'm on the stage,

like Muddy Waters or Howlin' Wolf or some of the guys I

hear on John R's radio show. I didn't know what

they would look like, but I could imagine in my mind that they

were dressed in these long tails. See, there was a Prince Albert

can that I could relate to. My daddy was smokin', and he

smoked Prince Albert. There was a man's picture on it that

had a long frock coat. All I could relate to, bein' dressed

to me, was -- I'm this famous cat, and I look like

this guy on Prince Albert. As a child, that was fabulous to me.

I would set the Prince Albert can on a table and visualize with

little capes around me, and I'd be tryin' to look

as much like this man on this Prince Albert can as I could, dress-wise,

because that represented stardom to me. I didn't know nothin'

else to relate to. There was no one that I knew in my family that

was famous or had the potential to be famous, that I could relate

to. I could only go by when I'd hear a Muddy Waters record

and things like that.

"No, I hadn't. I've been a dreamer all of

my life. I remember at six or seven, eight years old, workin'

in the cotton field. One time my mother hit me in the head with

a cup, because I was standin' in the field at 11 o'clock

or almost 12 o'clock in the daytime, lookin' up

at the sun, and the sun was just cookin' me. And I did

not see the sun, or feel the sun. I wasn't aware that I

was lookin'. My mind was gone into a deep thought, and

I could see myself onstage. Doin' what I do now. I could

visualize -- when I was 10 -- me bein' 20.

I'm a big man, I done grew up, and I'm on the stage,

like Muddy Waters or Howlin' Wolf or some of the guys I

hear on John R's radio show. I didn't know what

they would look like, but I could imagine in my mind that they

were dressed in these long tails. See, there was a Prince Albert

can that I could relate to. My daddy was smokin', and he

smoked Prince Albert. There was a man's picture on it that

had a long frock coat. All I could relate to, bein' dressed

to me, was -- I'm this famous cat, and I look like

this guy on Prince Albert. As a child, that was fabulous to me.

I would set the Prince Albert can on a table and visualize with

little capes around me, and I'd be tryin' to look

as much like this man on this Prince Albert can as I could, dress-wise,

because that represented stardom to me. I didn't know nothin'

else to relate to. There was no one that I knew in my family that

was famous or had the potential to be famous, that I could relate

to. I could only go by when I'd hear a Muddy Waters record

and things like that.

"I just went through names. I started to name myself Truman

Roosevelt. 'Cause it sounds good. I would listen to the

sounds of names -- there was a cousin of mine who's

named Bobby, and it had a ring, but Bobby's so common.

I needed a name that had the first name and last name as a combination.

What I mean about that, if you notice, everybody call me Bobby

Rush. I tried to pick a name where you say one, you say the whole

name, like one word. There's too many Bobbys, too common,

and there's too many Rushes, too common, but Bobbyrush,

there ain't but one of 'em. Bobbyrush. It's

double entendre too, like, I'm in a hurry, I'm rushing,

and quick to catch on, whatever you want to call it, slow but

yet fast. But I thought about the name for a year before I adopted

it for myself. Came out of the blue sky. Sonny Thompson asked

me one time, 'How you like your name?' I said, 'I

love it.' And nobody never -- since I adopted the

name, I always tell my real name, it's no big secret, but

people call me Bobby Rush, not Bobby, and I prefer people to call

me Bobby Rush. You don't have to call me Mr. Rush. A lot

of people who work for me call me by my last name, and that's

OK, but I do want people to call me Bobby Rush."

"I just went through names. I started to name myself Truman

Roosevelt. 'Cause it sounds good. I would listen to the

sounds of names -- there was a cousin of mine who's

named Bobby, and it had a ring, but Bobby's so common.

I needed a name that had the first name and last name as a combination.

What I mean about that, if you notice, everybody call me Bobby

Rush. I tried to pick a name where you say one, you say the whole

name, like one word. There's too many Bobbys, too common,

and there's too many Rushes, too common, but Bobbyrush,

there ain't but one of 'em. Bobbyrush. It's

double entendre too, like, I'm in a hurry, I'm rushing,

and quick to catch on, whatever you want to call it, slow but

yet fast. But I thought about the name for a year before I adopted

it for myself. Came out of the blue sky. Sonny Thompson asked

me one time, 'How you like your name?' I said, 'I

love it.' And nobody never -- since I adopted the

name, I always tell my real name, it's no big secret, but

people call me Bobby Rush, not Bobby, and I prefer people to call

me Bobby Rush. You don't have to call me Mr. Rush. A lot

of people who work for me call me by my last name, and that's

OK, but I do want people to call me Bobby Rush."