|

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

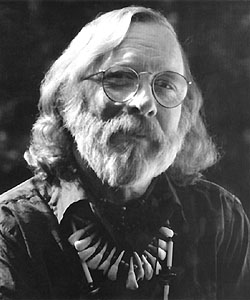

| maverick manchild | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

This column begins with an e-mail I sent to the wrong person. Or it actually started one night almost 30 years ago at a concert in Detroit — take your pick. Recently I sent an e-mail to a Portland photographer. Or I thought I did. Actually, it went to one Kathleen Stokes, who lives in Portland and who kindly wrote back, saying that she had no idea what photo I was carrying on about or why I contacted her, and she mentioned that she was the manager for David Rea. Hmmm. Backtrack almost exactly 29 years. I student-taught in Detroit in the fall of 1970, and I often hooked up with a college buddy to see live music. One particularly frigid night in November we made our way down to the Grande Ballroom, a funky old theatre in a seedy district, to see Van Morrison co-billed with the Siegel-Schwall Blues Band. As they often did back then, Siegel-Schwall — at that point Chicago’s most potent live blues attraction — blew young Van the Man off the stage that night, but that’s another story. There was another opening act, and his name was David Rea.

Maybe it was the nascent music critic coming out, but I watched in fascination as this bony kid with the scratchy voice won over at least part of the crowd, and me in particular, with some great songs and dazzling string work. (If I hadn’t thought, at that point, that Moondance was the greatest album of all time, I would have given up on its mercurial author after his bizarre set later, but that’s another story, too.) One Rea song in particular, a rollicking folk tune titled "Maverick Child," stuck in my mind. When I found a Capitol album of the same name a couple days later, I plunked down my three bucks. Besides the song I remembered so well, the record contained the first version I ever heard of "Hellhound on My Trail." I found Rea’s name on Jesse Winchester’s acclaimed debut album, purchased 1971’s By the Grace of God and 1973’s Slewfoot — recorded with members of the Grateful Dead — and read about his short stint with Fairport Convention (he briefly replaced Richard Thompson) before losing track of Rea, like so many others, when he stopped getting contracts from major labels. Could it be the same fellow? Indeed it was, Kathleen responded, and she sent me his e-mail address. Being inclined to take advantage of these kinds of occurrences, I shot an e-mail to him, we traded phone numbers and wound up talking about his career and blues connections before and after Maverick Child. Though Rea is most often classified as a "folk" musician, his blues roots run deep and inform everything about his musical inclinations and playing style. He just finished a tour in Canada with bluesmen Big Dave McLean and Mark Sterling, and his most recent album, Shorty’s Ghost, includes several familiar traditional blues favorites. I asked Rea why he recorded "Hellhound" way back when. Turns out that Robert Johnson was an early touchstone for Rea, who first got King of the Delta Blues Singers soon after its release in 1961. "I was about 12 years old when I first heard it," he says. "A fellow lived up the street, and he gave me records by Blind Lemon Jefferson and Henry Thomas, Etta Baker — one of my big influences — and of course, Merle Travis. "But Johnson screamed at me, so I tried to figure the tunings, you know, looking for the Rosetta Stone. In some cases it took me 30 years, but it was worth every minute." The obsession with Johnson’s chord structures led to the recording of "Hellhound" on Maverick Child. It also spurred him to write and produce David Rea’s Robert Johnson, a radio series on the Delta bluesman commissioned by the Canadian Broadcasting Corporation in 1988. "I sat down and wrote out a precis, a scholarly thing, and got in touch with Peter Guralnick, who was extremely generous with his stuff," Rea says. But that first draft was rejected. "They wanted a phantasmagorical vision of America through Robert Johnson’s eyes, so I wrote stream-of-consciousness pieces for each of his songs. One was a piece on aging; another was on why men are afraid of women, which figures heavily in Johnson’s world — he was terrified, and also a predator — and I interspersed those with the actual recordings. In the middle of that, I recorded a thing that would demonstrate the tunings." Born and raised in Akron, Ohio, Rea was classically trained and grew up with traditional music in his home, but he was also keenly aware of the emerging rock’n’roll. "We had the Allan Freed traveling shows and all the early rock DJs — Mad Daddy, Big Wilson," he remembers. By 1958 he found himself on Saturday afternoons in Akron’s black district. "I would hear Sonny Stitt, Sunnyland Slim, B.B. King, John Lee Hooker over at the Hi Hat Tavern on Howard Street — I’d have to stand outside the bars on Saturday afternoons ’cause I was too young. The rhythms fascinated me." A move to Toronto in 1964 put him in the middle of a thriving local music scene for the next couple of years. "Imagine you’re 18 in Toronto, and within a 15-block radius you can hear Ian and Sylvia, Gordon Lightfoot, Neil Young. John Kay is living upstairs, and downtown you got Ronnie Hawkins & the Hawks." Rea gravitated to a couple of other Toronto players. "The Rev. Gary Davis took me under his wing," Rea says. "A lot of people say, ’Well, I studied with the Rev. Gary Davis.’ But you didn’t study — you just kept your mouth shut and listened. Anything you wanted to learn, he would play over and over again. He had a very percussive style of playing." And he became friends with Lonnie Johnson, who moved to Toronto near the end of his life (see BA #32 for more on Lonnie’s last years). "The first night I saw him play, Lonnie gets up playing a cheap electric guitar. He had on a tux, and the first song was ‘I Left My Heart in San Francisco.’ And all of a sudden he looked around and realized that everybody had come to hear him, and there was a transformation onstage. He asked for his stool and played ‘Careless Love’ and ‘Tomorrow Night.’ I had to go out and cry because he was a man who thought he was forgotten, thought that nobody cared, and he played his heart out that night. I have to say that we were in the presence of greatness." As it turns out, he didn’t remember that Detroit performance in 1970. "That was during the days when I did a lot of rock’n’roll shows when I was with Premier Talent — mostly rock & roll because of ‘Mississippi Queen.’ What the hell, it was good money but very hard, unrewarding work." "Mississippi Queen" was one of the songs he wrote or co-wrote for Mountain in the early ’70s. He had met Felix Pappalardi while backing Ian and Sylvia. "It was love at first sight," Rea recalls. "He had been producing Cream, and he asked me to come to New York. "Corky Laing and I were sitting in a rehearsal hall at 36th and 10th, in a Hell’s Kitchen loft. I was working on ‘Maverick Child.’ Corky was at the other end of the hall. He said, ‘Do you know any towns in Mississippi?’ I had just been reading about the siege of Vicksburg. He said he was working on a song called ‘Mississippi Queen’ and that Leslie (West) didn’t want to work on it and neither did Felix. "So we hashed it out. Corky took it to Felix, and as things go, he added a few words, and Leslie added the guitar lick. About a month later they called me over, saying, ‘You gotta hear this.’ "God gives us maybe one great rock’n’roll song. I got it, and I’m proud of it." — Leland Rucker

|

|

|

It was the first time I had ever seen an opening-opening act, in this case

a lean folk singer with a cowboy hat, a red bandanna and an acoustic

guitar, standing out there in front of a stoned crowd on the verge of

rocking its collective eyeballs out.

It was the first time I had ever seen an opening-opening act, in this case

a lean folk singer with a cowboy hat, a red bandanna and an acoustic

guitar, standing out there in front of a stoned crowd on the verge of

rocking its collective eyeballs out.