|

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

JOHN MOONEY By the sweat of his brow by |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

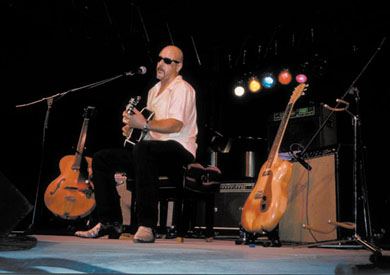

July 17, 1999 in Kansas City was just another typical three-shirt day for John Mooney. Arriving from St. Louis in the blast furnace heat of a midwestern summer to play the Kansas City Blues & Jazz Festival, Mooney sweats just standing still. His clean-shaven cueball head boils with beads of sweat. And he hasn’t even started playing. "I sweat like a hog," Mooney confesses. That’s an understatement. Stand next to John Mooney in the intimacy of a nightclub and you can feel the temperature in the joint soar as he wields his slide like a straight razor, slicing at his strings until they weep and wail. Mooney plays with such ferocity you swear he’s going to levitate. When he’s in full tilt, sweat flies off the guy like the burning notes shooting from his fingers, and his cowboy boots threaten to stomp a hole right through the stage. By the end of the song you don’t know if it’s your sweat or his that’s soaking your shirt — but it feels oh so good. Make no mistake: there’s more to John Mooney than sweat and fast playing. In a world of technically proficient players who all sound alike, Mooney has developed one of the most distinctive and easily identifiable guitar and vocal signatures of anyone alive today. His snaky, slide-drenched interpretations of New Orleans mambo and second-line rhythms come by way of the Mississippi Delta and weave a seriously funky groove through the blues that can turn your backbone to jelly. Couple that with a voice that could fill a room without a microphone, resonant with emotion and soaring and moaning with the ghosts of Son House and Professor Longhair, and you have a seductive musical cocktail that leaves you deliriously drunk with pleasure every time. It’s no accident that Mooney’s vocal stylings reflect the influence of House and Longhair (Henry Roeland Byrd). He learned under the tutelage of both. Already steeped in the blues at a young age, Mooney first met Eddie James "Son" House Jr. in 1971 in Rochester, New York, where they both were living. "I was 16 and I had been playing with Joe Beard and Fred Palmer. We did a trio together, acoustic, and I used to play National steel. And Joe said, ‘Hey, you know you play all this Son House and Robert Johnson, maybe you oughta just meet him.’ And I said okay, so he called Son up and one day we got together at Joe’s house, just played and watched. "We’d get together at house parties and stuff, so I’d bring a couple Nationals and it took him awhile to, like, let me tune his guitar. It took him awhile to kind of figure out, you know, ‘What’s this white boy doin’ ’round here?’ And then he could see I could play. So we started doing gigs together and hanging out together. "We’d go to the grocery store with Evie (House’s wife). She wouldn’t let us go in the store, you know. You’d see everybody hangin’ out in front of the store by the cigarette machine smokin’ and stuff. That’s because their wives wouldn’t let ‘em come in the store. It was the funniest thing." Evie, a deeply religious woman, would only allow Mooney and House to play spirituals in her house — none of that devil music — so they had to retreat to the front porch to play blues. House, being a former preacher until he laid down his Bible and picked up a guitar in his 20s, gracefully complied with her wishes. House’s big, booming preacher voice made an impression on the teen-aged Mooney that’s clearly evident today, particularly on the occasional a cappella spirituals he pulls out. "At Joe Beard’s house, when Son started singing we were sitting in his living room and Joe’s windows started to rattle. That flipped me out, like, how did you do that? I grew up in the country and lived on a farm, and so I used to go out in these fields and practice singing. Because the way it sounded, it sounded like it filled up the whole sky with his voice. So I’d sit out in these fields playing, trying to get that intensity. I guess it made me a loud street singer." Mooney landed in New Orleans in 1976 and eventually wound up backing Professor Longhair for awhile. By then, the lure of the Crescent City had been set firmly in his craw and he stuck around for the next 20 years, soaking up the rich musical vibes of its cultural wetlands. Mooney’s influences these days are all over the map. "I check out a lot of stuff. People give me CDs. I like Royal Fingerbowl, they’re good friends of mine from New Orleans. Carlo Nuccio plays drums with me. He plays drums for Royal Fingerbowl and produces their stuff. "Oh, and you know, the Wild Magnolias. That’s what’s been in my CD player: their new one (Life Is a Carnival). Bo (Dollis) and Monk (Boudreaux) are good friends of mine. A few years ago we toured France together. Like that song "Pocket Change" on their new CD is one I want to do. And when I saw Bo a couple of weeks ago he said they wanted to do [Mooney’s song] "Sacred Ground." Which is cool, because when I was making Against the Wall I wanted to start it with the version that’s at the beginning of the album, and then at the end I wanted to do another version with the Wild Magnolias. But then with our budget we never got around to doing it."

PICKING UP THE PIECES Mooney’s life took a nosedive in 1996, chased by the hellhounds of smack ’n’ crack, and he’s spent the past two years or so piecing things back together. He quit playing guitar for over a year and, except for a handful of sporadic dates, dropped out of sight until his triumphant return at the New Orleans Jazz and Heritage Festival in 1998. In order to deal with his personal demons, he moved his three kids and then himself to an island off Ft. Myers, Florida. "Basically, things were just out of my control in New Orleans," Mooney recalls. "And after going through rehab and coming out, I had to leave because the same problems were persisting and there was nothing I could do to change it. I’m walking around, you know, with a 12-gauge shotgun kicking people out of my house, and an hour later they’re back in the house. Well, I said screw this shit. I figured out a way to get my kids out, and then as soon as I could I followed afterward." Going clean wasn’t the hard part, Mooney says, it was leaving New Orleans and its vibrant music scene behind. "We’re there about every month to six weeks. I love being in New Orleans now because the people who I had a problem with also moved. They actually moved to Florida, so when I go to New Orleans they’re not there. So it’s cool. I’ll probably move back in a year or so." It’s hard to forget the "City that Care Forgot." Mooney is a man without a label. His most recent release, 1997’s superb Dealing with the Devil, was actually recorded two years earlier at a festival in Germany and picked up by Ruf Records. And his last studio album, Against the Wall in 1996, was Mooney’s first and only effort for the then-fledgling House of Blues label before he was swept out in a housecleaning there. None of that seems to bother him, though. "I’ve been talking to some label people and stuff, taking my time. There’s some people interested. I think because I don’t want to go out and drive around touring so much, some people go, ‘Well, you know you have to.’ Well, the fact of the matter is things are going so well I haven’t needed a record. It’s like, why? You don’t have a new record out, you haven’t put a record out in four years. Yet it’s growing and growing. I don’t get it, so it’s like, if it ain’t broke don’t fix it." Mooney has been happy in his role as housedad for the past couple of years. Staying at home during the week when the kids are in school, he and his Bluesiana band hit the road on the weekends. "Go out Friday nights, come back Sunday. In that time we can go about anywhere, you know — San Francisco, New York, Europe, Panama." That sometimes leads to some strange booking itineraries. "Trying to remember where you were last weekend is hard as hell. Like a couple weeks ago, Saturday we were in Oklahoma City, Sunday we were in Washington, D.C.," Mooney laughs. "When I got here today I called New Orleans to have this music shop put together a bunch of strings for me so Bobby could pick ‘em up. And since we stopped in St. Louis before we got here, I forgot we were in Kansas City and I said, ‘Yeah, I’m here in St. Louis.’ And he said, ‘Uh, John, I think you’re in Kansas City.’ He must’ve had Caller ID." Many of those dates are festivals, and such exposure of his live act to larger audiences than the usual cramped quarters of New Orleans nightclubs could explain Mooney’s rapid word-of-mouth popularity since his return to playing. Most first-timers simply walk away from a Mooney set shaking their heads and tend to show up the next time with a half-dozen friends. When not performing solo, Mooney fronts his Bluesiana band — usually a trio — which provides the necessary second-line rhythmic propulsion to showcase his guitar virtuosity and still leaves plenty of room for his yowling vocals. Their last two performances at the New Orleans Jazz and Heritage Festival have ranked as "Best of Fest" on many veterans’ lists. His head freshly shaved for his re-emergence, Mooney left the crowd aghast with his "bass surfing" antics at the end of his 1998 set, wailing away as he stood with one foot planted on bassist Jeff Sarli’s shoulder and the other in the crook of his stand-up bass. And during Mooney’s 1999 set rain came down out of a clear blue sky, prompting some Jazz Festers to take pause and contemplate the significance of all that. Most recently, the Bluesiana bass chair has been plagued with disaster. Sarli had a bad car accident earlier this year and was laid up for about a year. Then Blues Traveler Bobby Sheehan took over while his band was on hiatus and in August was found dead in his New Orleans home from what has been officially ruled a drug overdose. The percussion department has been more fortunate. Besides Carlo Nuccio, Mooney sometimes taps Kerry Brown for drums, and on special occasions uses both. Mike Skinkus or Alfred "Uganda" Roberts often sit in on congas as well, adding some pop to the bop. The extra flavors only serve to enhance the main dish, however, which is unmistakably John Mooney no matter whom he’s playing with. "I can’t really play ‘regular’ guitar," Mooney explains of his trademark style. "Years ago, when I was 12 or 13, by that point I decided it was just fruitless to try to play what other people were playing because I just wasn’t any good at it. So I’ve never been much at trying that. That’s why I don’t know all that stuff everyone else does." Few players are so prolific with a slide nor employ it with such demonic ferocity as Mooney. It’s not uncommon to see him play nearly an entire set without putting it away. Over, under, sideways, down, there are no rules when it comes to Mooney’s take-no-prisoners approach to slide guitar. With slippery, fluid strokes, he pushes and pulls steel on steel to coax a quavering, almost phantom-like voice out of the strings, punctuated by notes that strike like greased lightning and vanish just as fast. Mooney took part this past June in a slide-lover’s dream set at New Orleans’ Uptown Tipitina’s nightclub, along with his old friend Bonnie Raitt. "At one point we had her, me, John Lawrence from Stavin Chain, Deacon John and Spencer Bohren all playing the slide together," Mooney exclaimed. "It was wild. And then we had the Magnolias and Sheeba, who used to play drums with Fess, and Carlo and David Lee on drums, and Skinkus and Uganda both playing congas, so we had three drummers and two conga players. It was just wild!" Mooney and Raitt, another disciple of slide and bottleneck guitar, go back about 25 years. "We first met in New York City. I was traveling around with Roomful of Blues. I would sit in with them, or sometimes like up in Rhode Island I’d play in between their sets. I’d ride around on their bus. And they were playing at the Bottom Line with Bonnie, and that’s where I first met her. Helen Humes came out and sat in with Roomful. Helen Humes sounded great. It was when Duke Robillard was playing guitar and Al Copley on piano. So Bonnie and I go through periods where we stay in touch." Honeyboy Edwards is throwing down under the hot Kansas City night outside and Mooney cocks an instinctive ear while tuning up an unusual-looking new guitar of his. "This friend of mine on the island, he’s a woodworker and he’s always wanted to start building guitars. So we kind of designed this one and put it together. This wood is made out of a table leaf," he chuckles. "See, the table was stolen out of my house in New Orleans, but they didn’t take the leaves. So for experimental purposes I thought, let’s make it into a guitar. We call it the ‘bubble guitar,’" he says, noting its domed top. Besides converting his furniture to guitars, Mooney employs an arsenal of other commercially available models, including several vintage National steels, a 1951 National archtop, a Gibson 150 single-cutaway and a collection of Artex electrics. His amps include Fender Super Reverbs and Twin Reverbs and Bassman Piggybacks. Mooney hopes to produce another album with New Orleans roots rockers Stavin Chain this year. And he’s excited about writing and picking out songs for his next CD, whenever that might be. "You know Galactic?," Mooney enthuses. "There’s a song that Theryl deClouet wrote — he sings with them, and he and I are old friends — and he sings it really with me in mind. You know when I do some of that a cappella Son House stuff? It’s kind of along those lines. Except Galactic will play just an acoustic guitar and sax on this little line, and (drummer) Stanton (Moore) is just playing the tambourine. It’s really cool. I want to do that. There’s all kinds of different things I want to do. "I’d like to do another live one," Mooney concludes, and with good reason. His two live sets from Germany — 1992’s Travelin’ On and 1997’s Dealing with the Devil — are as good a representation of Mooney as any of his studio recordings, and both do a respectable job of bringing the intensity of his live shows into your living room. Of course, you have to provide your own sweat. Karl Bremer is a free-lance writer in Lakeland, Minnesota.

|

|

|