|

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

WILD INDIANS an interview with Big

Chief Bo Dollis by John Sinclair and Bill Taylor |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

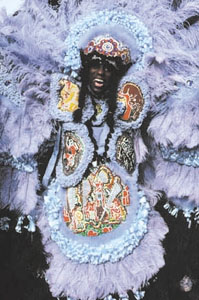

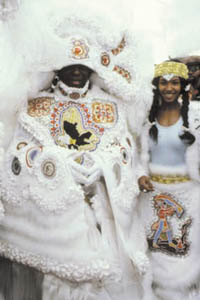

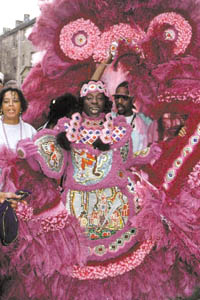

The legendary Mardi Gras Indians of New Orleans — African American citizens who mask as Native Americans in elaborate hand-crafted costumes made of beadwork, feathers and plumes — can be seen in all their splendor on Fat Tuesday, the one day of the year they’re allowed to run wild in the streets from dawn to dark. There’s nothing like seeing the Wild Indians in their natural habitat, emerging in all their magnificent finery out of the doorways of dilapidated inner-city houses and project apartments to strut and swagger down the middle of the beat-up streets where they struggle to make a living and somehow survive the crime, violence, joblessness and grinding poverty of their neighborhoods throughout the rest of the year. That’s the real-life context of the Wild Indians of Mardi Gras, and they exist today as the living manifestation of an age-old ritual, preserved and practiced by the descendants of the African slaves, which goes back to the perambulating societies of West Africa and their call-and-response chants, the secret societies of masked warriors which are common to both African and Native American cultures, and the unsanctioned moonlight ceremonies conducted by African slaves under pain of death on the plantations of the American South. It’s a ritual which continues to live in the mean streets of early 21st-century New Orleans, and in the hearts of the people of the most run-down, destitute, stripped-bare-and-left-for-dead underclass neighborhoods of the city, where the Wild Indians of Mardi Gras perennially represent the triumph of spirit, creativity and beauty of song and dance over every obstacle placed in their way.

If ya don’t wanna play,

But it all changed one Sunday in 1970 when Quint Davis, producer of the fledgling New Orleans Jazz & Heritage Festival, walked into an Indian practice and listened to Big Chief Bo Dollis of the Wild Magnolia sing the traditional chants. After the practice, Davis approached the Big Chief and asked if he’d consider recording his music with a band backing him up. Davis assembled an all-star R&B unit, the New Orleans Project — with pianist Willie Tee, guitarist Snooks Eaglin, Willie’s brother Earl Turbinton on saxophones and a smoking rhythm section — and took the Wild Magnolias and their battery of street percussionists into the studio with them to record a Bo Dollis original called "Handa Wanda." Released on 45 rpm, this single recording spawned a whole new genre of New Orleans music as it fused the ancient sounds of the Wild Indians with the new world of funk to create something that had never been heard before. Spurred by the enthusiastic response to the single from the patrons of street-corner bars all across the Crescent City, Davis secured a two-LP recording contract for the Wild Magnolias with Barclay Records of France and went back into the studio to cut a full album’s worth of material. Released on Polydor Records in the United States, The Wild Magnolias — with its irresistible rhythms, brilliant solo work by Snooks Eaglin and the lusty lead vocals of Bo Dollis — became an instant classic, introducing traditional Wild Indian songs like "Two-Way-Pak-E-Way" and Bo Dollis/Willie Tee originals like "Smoke My Peace Pipe" and "(Somebody’s Got) Soul, Soul, Soul." A second album, They Call Us Wild, was issued in 1975, and the Wild Magnolias took briefly to the road to explore a new career as stage performers. But Polydor failed to exercise its option for U.S. release of the LP, and soon the Magnolias returned to their Third Ward neighborhood and their traditional role as cultural preservationists. They continued to make an annual appearance on stage at the New Orleans Jazz & Heritage Festival, where they were joined by fellow Mardi Gras Indian gangs like the Black Eagles, Wild Tchoupitoulas and other established tribes. The Wild Magnolias’ professional career was revived in the ’80s by the late Allison Miner, who put a band behind them, booked club and concert dates, and landed a contract with Rounder Records. Their 1990 release, I’m Back … at Carnival Time, added a new layer of musical innovation when they brought in the Re-Birth Brass Band to accompany several Wild Indian numbers. On Super Sunday Showdown (1991) they collaborated with Dr. John and Willie Tee on two tunes and cut the relentless "Let’s Go Get ’Em" and "Shoo-Fly" with Re-Birth backing them up. A one-off album for AIM Records (Australia), 1313 Hoodoo Street, followed in 1996 before the Magnolias landed a deal with the Capitol Records subsidiary, Metro Blue, and released their major-label debut, Life Is a Carnival, in 1999. At this point their performing-arts career shifted into high gear when they assembled their current backing ensemble and began a round of non-stop touring which has taken them all over the world. Featuring the incredible Japanese guitarist June Yamagishi, the bass drum leads of long-time street percussionist Norwood "Geechee" Johnson, and a powerhouse rhythm section drawn from the city’s top funk players, the Wild Magnolias erupt on stage like nothing you’ve ever seen. Bo Dollis and Monk Boudreaux alternate on lead vocals, backed up by Queen Rita, Second Chief Gerard "Little Bo" Dollis, and other members of the gang in full Indian regalia, and they create a visual and musical spectacle beyond description. One hot May afternoon in the first year of the new century, Bill Taylor and I sat down with Big Chief Bo Dollis at the H&R Bar, uptown at 2nd and Dryades, to trace his personal history and the development of his unique musical vision over the past 35 years. — John Sinclair

That means I’ve got the blues and I go to singin’. I am going to sing those Indian blues. When I put on my crown, I’m goin’ down. When I put on my shoes, I got Indian blues. You’re ready to get on out there and sing them blues. That’s the whole thing. How did you originally become involved as a Mardi Gras Indian? Because of my neighbors who used to mask Indian, like Brother Tillman. I used to get up on Mardi Gras morning and follow them. They used to wear bells on their costume, you know, charm bells, and you would know an Indian was coming down the street by the bells going ching, ching, ching. At that time it was a light costume, they used mostly sequins, and the only person who had a heavy costume was the chief at that time. No one else could wear a big crown except the chief. I got interested because I would watch them sew, I’d pick some material up and go home and try the sewing. What was that gang? Creole Wild West. Big Chief Brother Tillman. And now you’re a Big Chief. How did that happen? Well, what happened was, we had about three Big Chiefs before me in the Wild Magnolias: There was Leon, he was the first Big Chief, and then Flap. Leon masked one year, then Flap for two years, then Joe Lee Davis for two years. Then in 1964 I became Chief. Was the crown formally passed down to you? Not really. We had a meeting, and we had no chief. So everybody voted. There were guys that had been masking Indian for over thirty years, but they all voted for me to be chief. I was young, and I’ve been chief ever since. Did you go out with the Creole Wild West before the Wild Magnolias? No, I was too young. I just followed them. At that time my mama wouldn’t let me mask — not with Brother Tillman, anyway. He was kind of rough. He’d come home at the end of Mardi Gras Day and his suit would be bloody, you know, he’d get into humbugs. They were still fighting then? Oh yeah, they were still fighting. But most of the time it would happen when they’d meet a gang from downtown, and I didn’t go that far. After Brother Tillman stopped masking, I would follow Robbie [Lee] and the Golden Arrows. He lived in Cabbage Alley, right by my house. I used to love to see him Mardi Gras morning with his feathered crown. He was one of the best in the 1960s. He taught me how to sew a crown. What does it take to make a new suit every year? Well, first you got to have patience. And you got to be dedicated to making the costume to the best of your ability — you got to have money and a lot of nerve. And you have to be able to take some punishment, because that needle will punish your hands. Why are you so dedicated to it? The people. I just love it when I come out of my house and there are people out there waiting. It’s unexplainable the way you feel. I remember one year I told everybody I wasn’t masking. But I was just telling them that. Oh yeah, I masked. There was only one year I didn’t mask, when my mama had died. Singing seems to be a big part of masking Indian. But you took that ability to perform on the street and brought it to the stage. How did that happen? I’d have to give that one to Quint Davis. He heard me at Indian practice. He went to check out Jake at the White Eagles Indian practice, and after I sang, Quint asked me if I’d be interested in recording a 45 with a band. He was a Tulane student then. I said, "Band?" I had never sung with a band before, but I said that I’d give it a try. So Jules Cahn, the photographer, gave us a building in the French Quarter where we rehearsed. Then Willie Tee came in. We needed a song, and I thought of "Handa Wanda." When we got into the studio, we made it so long it came out as Part 1 and Part II. What tunes were you singing with the gang at that time? You know, all the regular ones: "Smoke My Peace Pipe," "Golden Crown," "Iko Iko." But that 45 was something new. "Handa Wanda" wasn’t what you’d call a traditional tune. These songs tell a story that outsiders can’t really understand without knowing something about the Indians, and even then it’s difficult. Well, each Indian puts his own lyrics into the chants — singing about experiences on Carnival Day, what you did out there, who you met, if you made them bow, how you had a big crown, whatever. Some Indians sing what they hear others sing, but the ones who are really down into it, they just take it from their heart and express it out to the people. How was the reception to the "Handa Wanda" single? Great! I remember the first time I walked into a bar and it was on the box — on St. Bernard Street, at Sidney’s place. He was the first one to put it on his box. We did a lot of pushing the record ourselves. We had cards that said, "The Wild Magnolias — Ask for the new single." And they’ve been playing it ever since.

No, they didn’t really play the local records back then. It was mostly word-of-mouth, through people playing it on the juke boxes. After that first session did you have any idea that this would become a career? No, no. I thought after that 45, that was going be it. But Quint kept on searching around, searching around. Sending out promos to different record companies, then Barclay Records out of France picked it up, came over here, and we signed with them. They wanted us to do two albums. So we went out to Bogalusa, where we met Stevie Wonder, at the Studio in the Country, the first modern studio [in Louisiana]. You had a hell of a band behind you. Snooks Eaglin on guitar. How did he get involved? I used to go see Snooks almost every Sunday at the I.L.A. Hall [on Claiborne Avenue], where they had what they called the Booster Dance. So Snooks and Quint talked, and Snooks said, "Yeah, I’d like to gig with those Indians! Yeah!" So we were out there in Bogalusa, and Snooks, he cracked jokes all day. He’d say, "I can see what you’re doin’." [Snooks is blind]. He kept everything lively. Willie Tee [Wilson Turbinton], he was on organ. He did a lot of the arranging, turning Indian chants into straight-up funk. He got all the musicians together and just let them go. We had Zigaboo [Modeliste] on drums, Uganda Roberts on congas. Everybody just did what they felt. Like on "Handa Wanda," George French on bass, he was just great. Then on the first album, Julius Farmer played the bass. Man, the engineer couldn’t believe his touch. He was Fess’ [Professor Longhair’s] bass player. See, at that time Willie Tee led a band called the Gaturs. On the record he put together this all-star band, then for the tour we were backed by the Gaturs. We went to London with Professor Longhair. George Wein and Quint Davis took us. Great experience. Did you do anything in the U.S. at that time? We had our record release party in New York at the Bottom Line. The record company had decorated the whole place. Everybody in there had a Wild Magnolias tank top shirt. Did you have your outfits? Oh yeah. You also played Carnegie Hall back then. What was that like? It was an honor, but those people there weren’t givin’ it up! That’s when they were calling us "glitter rock." They finally got involved, clapping their hands. We did about half an hour, then Jimmy Smith played. I’ve heard Billy Delle, host of "Records From the Crypt" on WWOZ, say that if you were born ten years earlier, you would have been one of the great R&B singers of that illustrious period in the ’50s here in New Orleans. I’m wondering, when you were a kid, who were you listening to that helped shape your approach to singing? Roy Brown. Fats Domino, everybody listened to him. There was Smiley Lewis. Now, see, that was Dave Bartholomew behind both of them. The Wild Magnolias sound has a lot of that calypso and rhumba feel that Professor Longhair introduced to New Orleans music. Did you listen to a lot of his music? Well, when we were rehearsing for those first two albums, we would rehearse at Fess’ house on Rampart Street, the one that burnt down. He would get on piano, and you would have to turn and go the way Fess was going. It had that drive to it, irresistible. You still perform his songs today, "Big Chief" and "Mardi Gras in New Orleans." It’s like he wrote those songs for you! Oh yeah. He did so much with the Indian sound, Carnival tunes. Before there were Indian songs recorded, you couldn’t wait to hear his music during Mardi Gras. Also Sugarboy Crawford’s "Iko Iko." ["Jockamo," Checker 777, 1954]. Did you used to see Sugarboy play? Oh yeah. He used to practice at the Robin Hood on Jackson Street. It was a nice hotel, all the ladies in there. Did you ever spend any time at the Dew Drop Inn? When I started going to the Dew Drop, it was almost over with. That’s when Esquerita used to be there, and I didn’t like that. But we would go there on St. Joseph’s Night. We’d get there around 11 o’clock and stay until morning. Man, you’d look like a fool walking home when it was daylight with an Indian suit on! Back then they used to give out trophies for the best suits. How long has the H&R Bar been your home base? Since I started. There used to be a stage in here where Eddie Bo would play. Earl King used to play in here. There was a swing right up there. A chick in a gold outfit would get up there and swing! The ceiling was higher then. It was a hot spot. How did St. Joseph’s night come about?

So after St. Joseph’s night, in the old days, they would take the outfits apart? Yeah, they’d tear ’em down. Start working on a new suit. Now we use some of the same patches every year, but then you’d tear the whole suit down. Some guys would trade feathers with each other. There were only two places you could buy feathers then. Now people go to New York to buy plumes cheaper. More variety. When you started masking, were Indians still using real animal skins? Not really. But you might see a Witch Doctor — you don’t see too many of them anymore — with a live snake. A real snake, nice size. You played at the first Jazz Fest. There was nobody there. We started a parade on Canal Street. We went down Canal, hit Bourbon, then up to the park [now Armstrong Park], gathering a crowd along the way. They followed us through the gate. We also had [Big Chief] Pete and the Black Eagles, and [Big Chief] Jolly and the Wild Tchoupitoulas. Two years after that, it got big. When did you first perform on stage at Jazz Fest? The second year. With Willie Tee. Played every year since. Was that the first time Indians performed on stage, outside of the streets? That would be the first time, yeah. Didn’t Big Chief Jolly used to mask with the Wild Magnolias? Yeah, he masked with me for about three years, and then he told me he was going to try to bring his own gang from the 13th Ward. He asked me to come help him with Indian practice. He used to have practice that would start around three p.m. So Monk [Big Chief Monk Boudreaux of the Golden Eagles] and I would go out there to give him a hand, and his practice got to be one of the best. I heard he used to feed everyone and make sure everyone had a ride home. Well, that was the way Indian practice was. You had to have food. Jolly always had spaghetti. Pete used to have red beans at Third and Baronne. Those were the only Indian practices they used to have Uptown. Downtown they’d have the White Eagles, the Yellow Jackets, and [Big Chief] Tootie [Montana] with the Yellow Pocahontas. You and Monk have stayed close over the years. Two Big Chiefs from different tribes — that’s kind of rare to keep that association. Monk and I was raised together. He masked one year before me. We were childhood friends. So when Quint came around with that 45, he said we needed some tambourine players and background singers. And so Monk, Alligator June, Quarter Moon and Crip, we picked the ones that could play drums and cowbells. Monk still masks with a different gang, but we’re still friends and we still get out there and compete with each other. We’re together when we do shows. You have two different musical styles that complement one another really well. Monk does that traditional, and I do a more commercial style. What about Geechie [Norwood Johnson]? When did he get involved? Well, he wasn’t around when we did the 45, but he came on the first album with the bass drum. Your second album, They Call Us Wild, wasn’t released in the United States. Right, only in Europe. That record has some tunes that aren’t traditional Indian chants, but were written for that session, I think. "New Suit" comes to mind. That was a song written by Willie (Tee). What about "Fire Water." That’s mine. You now hear that at Indian practice all the time. It’s a good way to get drinks. Sing that, then pass the hat around. People put money in and everybody drinks beer, wine. If you want beer, you drink beer. If you want wine, drink wine. During Mardi Gras time, that’s what everybody drinks. People that never drunk wine before. Many years passed after They Call Us Wild until your next recording.Were you still performing? No. Monk started the Golden Eagles. Ice Cube Slim from California, he took Monk and the Dirty Dozen [Brass Band] out there. How did you get back into it? Allison Minor. She called me up, asked if I’d put a band together. I couldn’t think of no band. Then I got Geechie, and June Victory on guitar. Allison was our booking agent, and she started booking us in New York and Virginia and other places. Quint came in and started booking us at some of George Wein’s festivals. You did a record with Rounder. Yeah. We had I’m Back at Carnival Time (1990). Then 1313 Hoodoo Street (1996) off AIM Records in Australia. And now you are on Metro Blue, a major label, part of Capitol Records, with Life Is a Carnival, your latest release (1999). How does that feel? Oh it feels good. Yes, indeed! We have some major tours coming up. You have collaborated with Dr. John a lot recently. Yeah, he did some tunes on the Mardi Gras Indians Super Sunday Showdown album (Rounder, 1991). We did a number with Champion Jack Dupree on that, too. I did some chants on his tune "Yella Pocohontas." Wasn’t he an Indian as a young kid? Yeah, he used to mask with the Yellow Pocahontas, when they were Uptown. He died before our record was released, though. But Dr. John, I first toured with him in the ’70s. With the Commodores too, that’s when they had that hit "Machine Gun." And the BT Express was on that tour. How did you get all these different artists together to play on Life Is a Carnival? Well, Robbie Robertson, we played on his record Storyville. He brought us on Saturday Night Live. When he heard about the new CD on Capitol, he wanted to be on it. That’s his tune, "Life Is a Carnival." We changed the lyrics a bit. So then Doc [Dr. John] heard about it, and he wanted on. Cyril Neville and Davell [Crawford], we play with a lot. Allen Toussaint, we did his tune "Hang Tough." But we did like 30 tunes for that record. I did "Hoodoo Moon" — I don’t know why they didn’t pick that one. But Doc wrote some great songs for the record, like "Blackhawk" and "Cowboys & Indians." I love "Pock A Nae." Yeah, that one just came to me in the studio. It wasn’t written or anything. June Yamagishi plays some mean guitar on this record. We met June in Japan. He actually was our interpreter when we were over there. Then he asked us if it was OK if he’d come sit in with us. We said, "You play guitar?" After that he said he would come to New Orleans, and a year later, he was here. Now he has his green card and he’s staying. Now if we’re not playing and somebody needs a guitar player, they call him. He plays with Henry Butler too. What music do you listen to at home? WWOZ. That’s it right there.

|

|

|

When

you sing about Indian blues, what does that mean?

When

you sing about Indian blues, what does that mean? Did

it get any radio play?

Did

it get any radio play? That

goes back since the Indians started. They say the Indians and St. Joseph

were kindred spirits. And it was legal. The police wouldn’t do nothing.

Back then you couldn’t come out of your house without a lantern. And

it had to be lit. If it wasn’t lit, you were going to jail. And you

had to have your own lantern. I’ve seen plenty an Indian go to jail

without having one. Then, in the 1970s, we started carrying flashlights,

but now it doesn’t matter.

That

goes back since the Indians started. They say the Indians and St. Joseph

were kindred spirits. And it was legal. The police wouldn’t do nothing.

Back then you couldn’t come out of your house without a lantern. And

it had to be lit. If it wasn’t lit, you were going to jail. And you

had to have your own lantern. I’ve seen plenty an Indian go to jail

without having one. Then, in the 1970s, we started carrying flashlights,

but now it doesn’t matter.