|

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

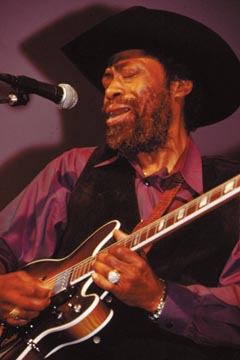

Son Seals Dues-Paying Bluesman Perseveres By Mike Emery The blues has always been about survival. Just ask any of the genre’s masters who are still performing today. Chances are, most of their works are semi-autobiographical accounts of surviving heartache, depression, unemployment and pain. But if you ask Son Seals about survival, he’ll simply shrug off the hardships he’s endured and the fact that he’s still around to talk about them. The veteran has no doubt seen the ups and downs of the music industry and has even been on the receiving end of a gunshot, fired into his face by a former spouse. And lately Seals has had to adjust to life without the use of his left leg, which was amputated a few years ago due to diabetes. While it’s been difficult to adjust to life after these setbacks, Seals says his creative output has not been affected. If anything, he’s still writing and playing the same powerful music that put him on the map 30 years ago. "Anytime I had a spell of sickness, all I’d want to do is get better so I could get back out there and play," he says. "I never thought, ‘God, let me get better, so I can get out there and write the "Diabetes Blues" or the "I Lost My Leg Blues."’ All I wanted to do is get better, so I could get back to work." In other words, don’t feel sorry for Seals. Although he’s faced one of the most terrible consequences of diabetes, Seals affirms that he’s the same musician he’s always been. His stage show, of course, has been dramatically altered as he now performs from the confines of a chair. But make no mistake about it, he’s still as sharp as ever when it comes to his fervent guitar work and robust voice. Then again, what do you expect from a man who’s been steeped in the blues ever since he was a child? Sure, almost every bluesman can recount the song or performer that inspired him to pick up a guitar, but Seals’ entire life has been spent listening to and playing the blues. Seals literally grew up in one of Arkansas’ top juke joints, the Dipsy Doodle, owned by his father, Jim Seals, who was an accomplished musician as well. So, under the tutelage of his dad, the younger Seals was able to learn music in the rural confines of Osceola, Arkansas. And since his bedroom was in the back of the nightclub, it was easy to see the legends of the idiom play on a nightly basis. "Musically, it was wonderful," he recalls. "There was music, music, music every night. People would pick me up and put me on their shoulders so I could see. And being close to Memphis, I got exposed to a lot of people: People like Sonny Boy Williamson, Robert Nighthawk, Earl Hooker and Albert King, who lived there before he moved to St. Louis and got on his feet." Coming up in such a creatively conducive environment, it wasn’t long before Son was playing alongside of some of the acts that frequented the Dipsy Doodle. "The first out of town act that I actually performed with was Robert Nighthawk, when I was about 13. His wife usually played drums, but she also sang. So, when they found I could play, they’d call me up and let me play some while she’d sing." His initial stage experience as a teenager made a deep impression on Seals, as did the number of quality acts he’d see and hear in his father’s rustic nightclub — particularly Albert King, who remains firm in his mind as one of the artists who inspired him to pick up the guitar. Like his father, Seals learned a variety of instruments. Dad Jim was once a member of the renowned Rabbit Foot Minstrels and was proficient on trombone, guitar, piano and drums. The younger Seals started with the piano, learned some basic drum skills and finally made his way to the instrument that would bring him fame. "It was like anything else: When you’re around it and see everyone else doing it, then you want to do it," he says with a chuckle. "Most musicians you run across will pick up more than one instrument. Look at my daddy and all of the different things he played. Once I got started, the guitar was something I really wanted to do. My dad helped me out a lot, and people like Albert King. I finally figured, ‘Hey, this is what I wanna do,’ and stuck with it." Seals says his father handed him his old Harmony acoustic, and Son placed a few pick-ups on the back of its neck to turn it into a make-shift electric model. After Son began to show some promise, his father pulled out the Sears Roebuck catalog and bought him his first electric model. "He bought me a Silvertone, the best one that they had at that time. I think he paid $165 for it."

His experience in the early ’60s would pay off by the decade’s end. But despite all the lessons he was taught by bona fide blues masters and journeymen musicians, Seals and other up-and-coming blues acts were eclipsed by the then-burgeoning British pop acts who covered American blues standards. So, while the Rolling Stones, Yardbirds and Cream would achieve international fame, indigenous American talents like Seals remained unknown to the musical public. Still, he doesn’t harbor any frustrations over that period — in fact, he’s somewhat grateful that the Brits were able to bring to light a music that had otherwise been restricted to juke joints and the chitlin’ circuit. "You probably get some blues guys who say, ‘Rock’n’roll did this and did that.’ I disagree with that to a great extent because, had it not been for a lot of rock groups coming along and picking up on music from Muddy Waters and Howlin’ Wolf, then who knows how long the blues would have stayed on the back burner. That’s not to say that the blues is getting the recognition it should be getting. But the airplay is a hell of a lot better than it was in the ’60s and ’70s." Son left Arkansas for good and moved to Chicago when his father passed away in 1971. The Windy City scene had long been filled with promise and, upon his arrival, Seals was not disappointed. "I had visited here in the ’60s," he says, "and going to the various clubs and things, it was very much like being home," because many of the blues musicians were also from the South. Son first found employment in Chicago backing up Junior Wells and soon hooked up with Hound Dog Taylor after a falling out between Taylor and his regular guitarist, Brewer Phillips. Blues enthusiast Wesley Race heard Seals at the Flamingo one evening and was blown away by the raw intensity of Son’s solo work. Race rushed to a phone in the middle of one extended jam and called his friend Bruce Iglauer, whose Alligator label was just starting to get off the ground, and Iglauer too was impressed by the upstart young guitarist. A few weeks later, Iglauer dropped by the club to catch Seals and extended an offer to record for his label. Seals accepted, and soon his debut album, The Son Seals Blues Band, introduced many blues fans to the man from Osceola, Arkansas. Listening to the album today, the sound is remarkably raw — so raw it’s almost difficult to imagine that this product actually emerged from a recording studio. Though the production seems incredibly thin, the record actually comes across as if it had been recorded in some Southern beer hall. Seals’ guitar leaks just the right amount of distortion, but the music maintains a tightness by means of Son’s staunch solos set against disciplined arrangements. His voice, on the other hand, shows a man just beginning to explore his abilities as a frontman. But dark, sultry originals like "Your Love Is Like a Cancer" and "Sitting at My Window" reveal Seals in his prime, stretching his emotion and delivery to their limits. The record helped launch his career and, although he never achieved the same level of fame as a B.B. King or Muddy Waters, Seals’ celebrity status ascended thanks to consistent recordings and an appearance in an Olympia Beer commercial. While mainstream ’70s America was enticed by disco and arena rock, blues enthusiasts and college kids became hip to Seals’ unique and sincere stylings. Among those were some hippies in Vermont, who later became one of the hottest touring acts in the United States. "The band Phish covers some of my music," says Seals. "They told me, ‘Hey man, we’ve been digging your music and seeing you play since we were still in school.’ That’s an honor to hear that kind of stuff." Flattery will still get you anywhere, but in this case, it worked twofold: The friendship between Seals and Phish blossomed into a professional alliance that’s found the band enlisting the aid of their hero on a few dates. Fortunately, it’s also worked in Seals favor as well. "The first time I went on stage with them was in Syracuse," he says. "There was an audience that day of 75,000, and at least 95 percent of those people probably didn’t know who the hell Son Seals was. After that particular appearance, I always run into people who say that they saw me at that gig." The collaboration didn’t end there. On Seals’ 2000 Telarc release, Lettin’ Go, Phish guitarist and frontman Trey Anastasio guests on a brand new version of Son’s "Funky Bitch." The updated Seals classic is still in raw form, with Anastasio’s flexible guitar lending some diversity to the mix. Lettin’ Go also finds Seals enlisting the help of other rock veterans, including Late Night guitarist Jimmy Vivino and studio vet Al Kooper. The result is a tightly produced collection of contemporary blues featuring diverse compositions and flashy horn arrangements. Seals followed the release of his Telarc debut with relentless touring on the club and festival circuit, playing a set that combined his earlier material with works drawn from the new album, and 2001 will probably be no different. Despite the loss of a leg, he’s not going to sit still, and he’ll be damned if his bout with diabetes is going to keep him from doing what he’s done all his life. After decades of roadwork and a fat catalog of recordings, some musicians might be ready to hang it up, especially after being diagnosed with a serious ailment. Son Seals will be the first to admit that he’s not getting rich as a blues musician, and he’ll also say that there’s not much glamour and luxury in the blues end of the music business. People get ripped off, and raw deals are a frequent occurrence. But, Son says, despite every physical and emotional obstacle he’s faced, his passion for the music is enough incentive to keep going. Most of all, he wants to keep it real — no keeping up with the Joneses in terms of blues fads or trying to relate his recent mishaps to music. As he puts it, the key to making good music is being honest with both himself and the audience. As long as he can continue to do that, he feels his career is still on the right track. "You have to bring out what you are," he says. "You have to be able to trigger what’s inside of you when you write and when you play. Let yourself emerge. You have no control over that. You just play what you feel and how you feel. That’s what I do, and I plan to keep doing it as long as I can. |

|

|

The

investment paid off. At age 18, Seals took command of his own band,

playing lead guitar and singing. But when touring acts would drop by

the Dipsy Doodle, he’d be more than happy to handle the drumming chores

for them. This led to his first professional engagement in 1960, playing

drums for Earl Hooker. He toured with the veteran guitarist and soon

hooked up with fellow Osceola native Albert King, even playing on Albert’s

classic Live Wire/Blues Power album for Stax Records.

The

investment paid off. At age 18, Seals took command of his own band,

playing lead guitar and singing. But when touring acts would drop by

the Dipsy Doodle, he’d be more than happy to handle the drumming chores

for them. This led to his first professional engagement in 1960, playing

drums for Earl Hooker. He toured with the veteran guitarist and soon

hooked up with fellow Osceola native Albert King, even playing on Albert’s

classic Live Wire/Blues Power album for Stax Records.