|

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Buckwheat Zydeco Up

from the Roots, Article:

Mark Varney

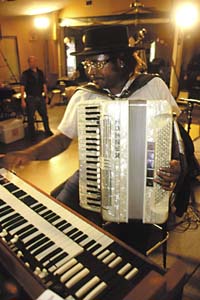

As the reigning king of zydeco, a unique form of regional music, Stanley Dural, Jr. — much better known as Buckwheat Zydeco — must constantly juggle three potentially conflicting concepts: purity, tradition and popularity. With every performance and every choice of material, Dural must think of ways to keep the music vital and accessible while remaining true to its cultural origins. And, with only a few exceptions, he has accomplished this very tricky feat. “I don’t close my ears to anything,” Buckwheat says. “I’m music crazy. I may hear just part of a song and, if there’s something there I can pick up, I use it. But if I do a cover tune, I make it my own.” Perhaps the most obvious example of Dural’s ability to make a song “his own” is his version of the Rolling Stones’ “Beast of Burden” — a song he has recorded which has become a mainstay of his live shows. In the days before Dural turned his full attention to zydeco, he and

his band — then known as Buckwheat & the Hitchhikers —

had to play covers if they wanted to work. “I loved the Before he joined Clifton Chenier’s band as an organist in 1971, Buckwheat had no real interest in zydeco. Like most young people, he resisted the influence of his elders and, in particular, the influence of his own father, himself a zydeco accordionist.

“It just wasn’t me at the time,” Buckwheat says. “I

was into funk and R&B. Zydeco seemed out-dated. It wasn’t until

I started hearing what Clifton was doing with the accordion that I decided

to go back to my roots and start to learn that.” Of course, Dural was lucky to be working with Chenier, the undisputed master of zydeco who became his teacher and mentor. Buckwheat’s decision to take a serious approach to zydeco and the accordion — the music’s most identifiable emblem — was more than a musical choice: It was a conscious effort both to get in touch with his own heritage and to revitalize the idiom so that it would not become another stagnant form of indigenous folk music — something heard only on Library of Congress field recordings. Dural’s idea was to retain the original spirit of the genre while infusing it with elements of rock, pop and soul in order to turn on up-and-coming generations to the black Creole music of southwest Louisiana, and for more than 20 years he has done just that.

This respect comes through in Dural’s music and in his astute comments about the music as he explains its importance as something more than just disposable pop. He insists that even though zydeco is “happy music,” it is also an offshoot of America’s most valued contribution to the world at large — the blues. “If you’re just playin’ to make a dollar, I don’t respect you,” Dural says adamantly. “I’ll walk away from you. I’ll see you on the flip-flop. You can’t change oil to water. You can’t change the blues. My motto is: what goes around, comes around. Everything you hear comes from the blues. “When I decided to play this music,” Buckwheat concludes, “I decided to play my grandfather’s music, my father’s music and my music. I took it to a different level. I can take it wherever I want to. But if you don’t stick to the roots, what’s the point?” |

|

|

Stones’

early stuff,” he recalls. “In those days we had to play what

was on the jukebox just to get in the door.”

Stones’

early stuff,” he recalls. “In those days we had to play what

was on the jukebox just to get in the door.”

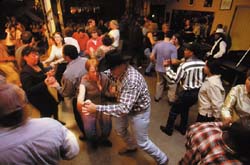

Buckwheat

Zydeco and his powerful 11-piece group have made their reputation as

one of the best party bands in America. They can make an audience jump

from their first few bars and keep it in a high-spirited, nearly hypnotic

trance through the last encore. Their music, with its sense of fun and

unrelenting joy, projects an honesty and a feeling of playing music

for all the right reasons that seems to touch something in people, even

if some of the audience may have never heard zydeco before.

Buckwheat

Zydeco and his powerful 11-piece group have made their reputation as

one of the best party bands in America. They can make an audience jump

from their first few bars and keep it in a high-spirited, nearly hypnotic

trance through the last encore. Their music, with its sense of fun and

unrelenting joy, projects an honesty and a feeling of playing music

for all the right reasons that seems to touch something in people, even

if some of the audience may have never heard zydeco before.

“I’m not out there to make money,” Dural says. “You

got to love it. To play, you’ve got to really respect what you’re

doin’ or you’re mistreatin’ it.”

“I’m not out there to make money,” Dural says. “You

got to love it. To play, you’ve got to really respect what you’re

doin’ or you’re mistreatin’ it.”